Linda (8)

By:

July 21, 2011

HILOBROW is proud to present the eighth installment of Karinne Keithley Syers’s novella and song cycle Linda, a hollow-earth retirement adventure with illustrations by Rascal Jace Smith. New installments appear every Thursday.

The story so far: Linda, a retired math teacher we met in Knoxville, has been wandering around in a place called the globe, a kind of experimental high stakes game world, for a while now, without a clear sense of the stakes or the game. Taken underground and plundered for a radio part jammed between her teeth, she recently encountered a young radiographer called Bessad. While Bessad was setting up the radio, she escaped, but we found her driving west in Al’s van, and sent her back into the globe. When we left her last, we thought we saw her companion dog-Linda greeting her in the forest.

16.

The first night she spends on the forest floor she finds she is glad to be back. They sleep knitted into each other: dog-Linda draped over Linda’s legs, head pressing on Linda’s belly, with Linda’s one hand is slid under the dog’s chest, the other on the dog’s ear.

When they wake, they go walking, through the dapple green of the Missouri forest, passing groves of Custard Apple, Birch, Catalpa. One grove is covered entirely by Trumpet Creeper, and looks more like a puppet mountain range than a stand of trees. Climbing under it they pass into an expanse of thick, dense canopy without undergrowth. Dog-Linda disappears occasionally, reappearing from odd angles and barking at Linda to follow. Zig-zagging to the dog’s directions, they find an old footpath along a creek, and follow it until the creek narrows into a trickle and the trickle narrows into a spring.

There is something off about the water: what passes out of the ground has a weird opacity, though this drops away within inches of the spring, becomes normally clear. The spring doesn’t so much bubble as cough. Linda lies down, ear against the ground, and hears a strained wheezing below the damp dirt. Dog-Linda moves to drink from the stream but backs off after taking her first lick of water. But when Linda tastes it, she finds it clean, likes its mineral taste. If she could have seen herself from above, she would have recognized herself properly as a nurse at this outflowing, this wrong puncture in the surface of the globe. But she can’t see herself as she leans in close on all fours to listen to the wound, and can’t interpret the signs or sound, or conceive the surface of the globe a kind of body, or its strangeness a kind of sickness, or the outflowing a kind of call, and for this reason the water turns clear, adopts a normal cast, abandons message.

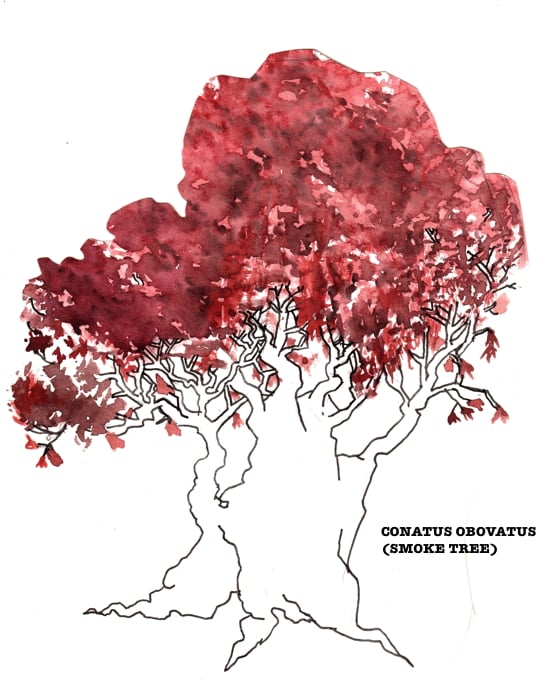

This spring is in a rocky, sloping clearing, and in the middle of the clearing, roots exposed as they reach over the rocks and down, appears a smoke tree. The smoke tree, with its clouds of miniature flowers, is one of Linda’s favorites. In the school where she taught math to 10th graders there was a faculty courtyard with benches and a few smoke trees and she often ate lunch there. In the days before smoking was banned from occupational places this was where she would come to smoke with her colleagues, especially the assistant principal Mr. Andrew Nestle, whose wife Colleen was Linda’s husband’s niece. On this smoke tree, which is knobby and old, there is one of those tree identification plaques customary of the parks service, white lettering etched in green plastic and an official insignia. She moves in to look the inscription which reads, Conatus Obovatus (Smoke Tree). The insignia is not of the State of Missouri, but is instead a circle with a tree in it whose roots form an empty, open space, making a circle within a circle, and within that circle is a silvered outline of an egg. Linda looks up at the tree, its gold-green underside faint against the profusion of red-grey bursts of tiny flowers that give the tree its common name. Some of these flowers fall on Linda’s hair and on her shirt, staining it with orange circles haloed by piss-bright yellow.

Dog-Linda, meanwhile, scouting the hilly, tufty place behind the tree, has found a metal door in the slope. When Linda comes to the dog’s side, the dog unfurls a howl of three distinct notes, and the door opens inward. They walk down steel stairs into a large room hollowed out of dirt, with whitewashed walls in which can be seen the fingery roots of the tree. There is a glowing light hanging low in the center, and skirting the sides are piles of wooden crates stacked into makeshift shelves. Around the low globe of light is a circular bench of dark wood, and on the bench on the far side of the light sits Bessad, facing away.

“Oh,” says Linda, who feels this time not fear but sympathy for Bessad, who is after all younger than her youngest. “Hello. Again.” Bessad turns, looks at her for ten full seconds, evaluating something, then turns back saying nothing. The dog leaves Linda’s side and walks to Bessad, licking his hand. After a minute he stands up, and together Bessad and dog-Linda walk to a curtain in the wall, pull it aside to pass, and disappear down a corridor, abandoning Linda to her unanswered greeting and the Knoxville sound of her voice, which we all have forgotten, she speaks so little in this story. She walks to the bench and sits down and waits. Nothing happens. She can hear the gastric juices in the low hum of her body.

After an hour she becomes cold so she crosses the room to rummage through the crates, returning with a wool blanket and a small volume covered in dark blue paper with a silver imprint of the double circle insignia. On the inside cover is printed, MILLS COMMISSION REPORT ON THE RESEARCH OF PROFESSOR BYRD FRIEND, 1974-6. She lies down on the bench and begins to read:

“To the old aphorism of Aristotle, that we do not want to do things because we find them good, but find them good because we want to do them, I only to add that the “we” in question is menacingly expansive. I did not want to undertake this expedition and I did not find it good. If I had my way, I would still be living a commonplace life in a commonplace town surrounded by my family, dear to me but no more remarkable than any of my neighbors. This was not my fortune, and it does no good to regret its passing, and to my family, if they ever come to realize that these reports are the reports of that same man they considered husband or father — for clearly I have changed my name, like any voluntary or involuntary partisan — I wish only to say that we can neither determine what calls us nor can we always choose to resist that call.

“The call for me came one afternoon when I was at home teaching my youngest to mow the lawn. My wife came to the porch and told me I had a phone call from Italy, or maybe Switzerland. The connection was overwhelmed by static and I could barely make out the voice on the other end. I should tell you now that my area of expertise had hardly seemed likely to lead to a life of adventure, and certainly I never expected that as a marine biologist specializing in squid that I’d be useful to any project not located within the oceans.

When the voice on the other end of the line identified itself as belonging to Alexandrine Humboldt, I thought one of my students was playing a joke on me, as my early work had been on the Humboldt Squid. Professor Friend, the voice said, I am quite serious. We need you immediately on the Oregon coast. She told me that my department chair had been notified, my absence approved, and that I would be picked up immediately. I apologized to my son, packed an overnight bag, and walked out front. I will forever remember the curve of the hedges that lined the poured concrete walkway out to the driveway, the single blossom in the Magnolia tree that bloomed erratically, never more than two or three flowers at a time, all year long. The sky that day was overcast. My older son was shooting a basketball at the frame attached to our garage. The color of the house, just painted, was taupe with white borders, and my son’s shirt was solid red. I got in the car waiting for me in the street, and never returned.

“I cannot say what path we took away from my home. It was long, the windows were dark, and I slept on and off for what seemed like a whole day and night. There was a small cooler in the car, stocked with sandwiches and water. The driver faced away from me and never once spoke except to offer me a thermos of coffee. When we arrived at what I had expected to be the Pacific, I realized with one breath of the air I had been misled. We were nowhere near water. A woman dressed in scruffy jeans and an army sweater opened the car door, welcoming me and thanking me and asking me to follow her into an opening in a hillside. It appeared to have once been a mine-shaft, now with whitewashed earthen walls and a comforting glow coming from a string of lanterns that led into its interior. It was difficult to make out what direction we were traveling. After a long walk absent explanation or communication, we arrived at a vast underground lake, and I saw something glowing in the center of it, that I guessed was a kind of squid.

“What can I tell you about what came next, that you would actually believe? That it was a squid about to give birth, not to baby squid but to tiny trees, that it was filled with phosphorescent seedlings? That I had been asked here to assist in a monstrous birth that was at the same time the most astonishing thing I had seen, a kind of love across not just species but across kingdoms? That here, underground, toward the end of the 20th century, a group of people were midwifing a kind of magic dismissed as the fantasy of an analogist at least 400 years ago? We don’t do it because we think it’s good; it’s good because we find it wants to be done.”

Linda puts the book down, feels suddenly and intensely nauseous, and passes out from the blinding pain of a headache that has swept in like a tornado come out of no where into the Iowa of her mind.

17.

The room is strange, it is strange. Linda awakes and finds it strange. The book is gone and she has been moved from the bench to a large couch. She is now around the corner from the entry room. As she walks around she discovers a series of almost obscured tunnels radiating out of the room, cutting back at angles from the wall in ways that, in all the dim, the openings are obscured until you come immediately upon them.

She tries one tunnel, its velveteen glow inviting. Down a short soft corridor, she finds a small room, almost just an alcove. Nestled into an ledge in the far wall is a small tank, and in the tank a colony of tiny glowing squid. She places her hand in the water and they move toward it, forming a kind of hovering glove, a tent on her hand, and so she pauses. The squid are translucent, and she can see their arborescent nerves, which they seem to have in uncommon quantity, as if equipped to propel a further set of squid arms not visible to the naked eye. All clumped together like that, the nerves, which glow like small neon tubes within the translucent bodies, form a kind of network. Linda studies the pattern. Without her reading glasses the lines are blurred, so she leans in closer to the tank, left eyeball squinting and right eyeball hovering over the assemblage of squid in turn hovering on her hand. Air from her nostril hits the water, and as it does, the picture shifts to a new pattern.

Linda thinks it would make a nice embroidery. Squinting, she leans in again and again the pattern shifts. She waits, and it shifts again, then again. She wonders if there is a communication all this, or maybe just pleasure on their part of the squid, like making a kind of music. She coughs a little and again it shifts, clarifying this time almost into a moving pictogram, something spidery, like a nest of spiders casting out onto the air. Her cheek is so close now that she can almost touch the squid, the top layer just below the water which is just below her cheek. But a sound of someone walking startles her, and as she jerks up the squid disperse, repelling backward from her hand to the side of the tank, then floating slowly down.

She wipes her hand on her pants, and braces as a wave of nausea hits her. She stumbles to the wall to steady herself, putting her cold hand on the back of her neck, leaning over almost touching her head to her knees as her stomach juices creep up her throat in a flush of heat. She hears the footsteps stop.

Once she has regained herself, Linda walks back out to the room where she woke up, and here meets Bessad and dog-Linda, who licks Linda’s hand. Bessad, self-possessed and showing none of the feeling of anger or failure but maybe more actually glad to be starting over with Linda, hands her some bread. She eats, giving the last bite to the dog. “Please,” he then says, gesturing toward the entryway, “we’re waiting for you.” They walk back to the circular entry, dog-Linda nudges the curtain aside, and they enter the tunnel.

And now, listen to the next song in the Linda song cycle, Cite Me:

NEXT WEEK: Linda goes down the tunnel, receives a startling message, learns to activate the globe, abandons benevolence. Stay tuned!

Karinne and HiLobrow thank this project’s Kickstarter backers.

READ our previous serialized novel, James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox.

READ MORE original fiction published by HiLobrow.