Pop-Up Apotheosis

By:

February 7, 2011

Here at HILOBROW we’ve been showcasing cases of near-nostalgia; technologies that didn’t quite have enough of a day, back in theirs. There have been revivals of susperseded signposts that were, perhaps, ripped down too soon in our race to the future; no one said the information superhighway had to be a one-way street. In turning around and revisiting some of these roads not taken (for long), a number of these markers have been refaced and repointed, and may now indicate new directions.

To our haul, which includes both analog and digital photography, cassette tapes, and even cave drawings, we may add the pop-up book. In researching pop-ups for a potential film collaboration with HiLobrow editor Matthew Battles last year, who profiled contemporary examples of pop-up book videos here previously, I sought out early examples of the tech; we thought to make a new film with an old look. So just how far back in the day was the day of the pop-up?

As it turns out, not very far back at all.

Out in the world of paper and things, the codex is more interactive than the scroll. Pages must be turned, and turning, rise and fall through the plane of comprehension. However, they are read flat and, despite their objectness and interactivity, are read as flat. And there they stayed for most of their history.

Not that the world stayed flat. It was discovered to be round, but even long before that, we were not content with surfaces. We thought “up,” and up we built. But despite our cathedrals and towers and obelisks and all manner of priapic construction with rock and metal, no one thought in that way about paper until very recently.

[Obelisks at Karnak, Egypt]

[Petřín Lookout Tower, Prague, Czech Republic]

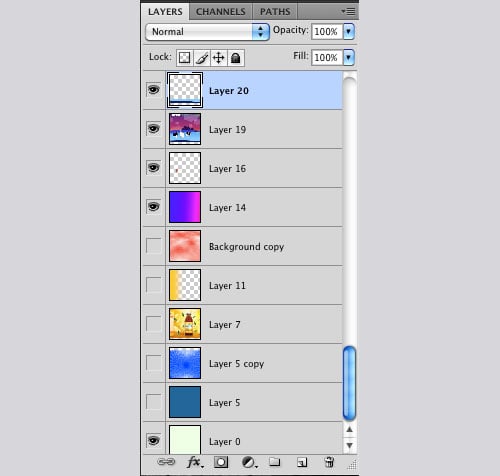

Not that there wasn’t plenty of lateral movement, and spinning around in circles. Medieval volvelles owed much to their navigational and astronomical peers, while the renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius famously employed liftable flaps, to show placement of veins, bones and organs beneath the relevant coverings of skin — anticipating both the acetate overlays of biology textbooks, and the driving metaphor of Photoshop.

[Astronomicum Caesareum, illustrated by Michael Ostendorfer, written by Petrus Apianus, 1540]

[detail of astrolabe from the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, Harvard University]

[Tabulae Sex, Andreas Vesalius, 1538]

It is significant that anatomy was among the first subjects for moveable books. Books are a stand-in for the body; they have comprised our corpus of knowledge for centuries. But perhaps they are closer to automata: easily spanning distances that would consume several generations of butterflies, and surviving the grave. Our tree of knowledge is repurposed therein, pulped and flattened to host further forbidden fruit. Flaps and overlays that veil deeper truths are never automatic, but must be chosen and manipulated, each in turn. The sharp intake and thrill of discovery is commensurate with that which is revealed: there are layers upon layers.

Early content of moveable books often mirrored these concerns. Along with forbidden knowledge, and unveiled bodies, came a LOT of instructions on how to behave.

[Harlequin Hangman, or, The miser punish’d, 1779]

[The Toilet, Stacy Grimaldi, 1821]

You might think the 19th century, with its new theories about childhood development, and the explosion of new toys to meet them, as well as its general love-affair with mechanism, would be the appropriate time for the rise of the pop-up. And yet, not so. Despite a rise in popularity of moveable books, and an increase in sophistication in their construction, creators hewed to the x-y axis, creating interlocking synchronies of movement out of stiffer paper, and some wire, that slid and shifted back and forth, and occasionally sounded, but never rose above. And although some of these pull-tabs and sliders operated by the opening of the page, most of them remained inert until pulled by an additional motion. In a way, just a more elaborate lifting of the flap, without the lift.

[Dean’s Moveable Cock Robin, 1858]

[The Monkey Theater: a moveable toybook by Lothar Meggendorfer, 1893]

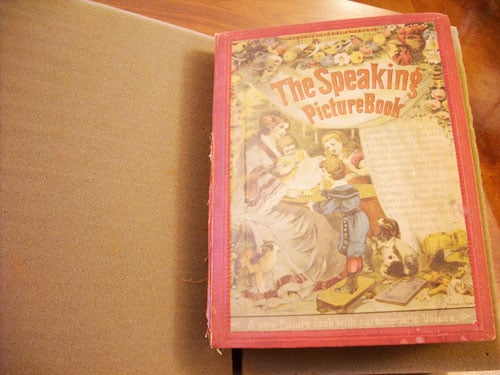

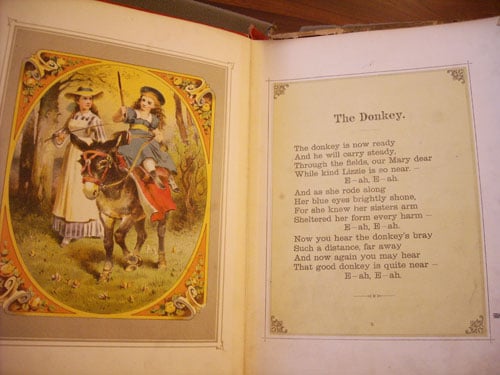

[The Speaking Picture Book: a new book with characteristical voices, 1893. The mechanisms pictured here still sounded reasonably like the animals they were intended to mimic, even after over 100 years.]

Among the tidal pool of antique watch collectors there is a further eddy that collect only watches of a certain type. These watches, in addition to telling the time, tell another story, often hidden by a false back cover. The gears moving the hands also animate a familiar motion among other figures riveted to the back along key joints. Although the mechanism employed is more sophisticated than that of moveable books of the time, the resulting action is remarkably the same. A simple sliding along the x-y axis, back and forth, until the watch, or interest, finally winds down.

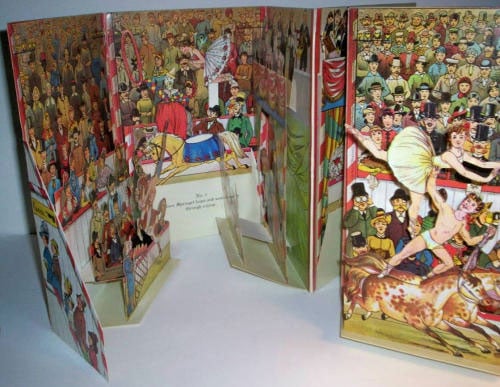

Other paper constructions, such as toy theaters and paper dolls, also gained in complexity and popularity. But these creations stood independently — although upright, they did not pop. Surprise was diluted in the construction of the small bodies, and although one could then arrange and narrate and animate various scenes; that slight automatic suspension of disbelief was itself, suspended.

[International Circus, Lothar Meggendorfer, 1887]

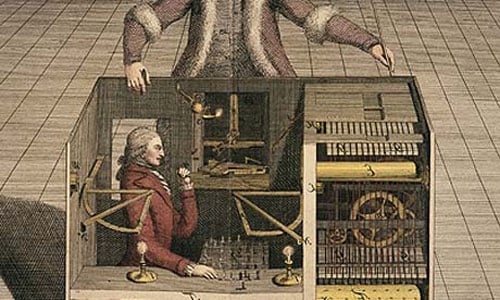

Pop-ups are closer in spirit to automata than to their sliding paper brethren. In the popping-up of a character or an entire scene or world, there is a moment’s thrill, as the imaginary land in the book springs — almost — to life. Not quite alive, it is, in that split second, liminally lifelike, as if maybe, just maybe, it will leap off the page, dance around, perhaps do more. Clockwork-driven automata provided this same thrill, regardless of whether they concealed a man within the mechanism.

[Mechanical Turk]

Will it speak? Will it initiate independent action, independent thought? This is what we want of independence in our constructions. Not that they stand alone, but that they might choose to stand; near us, or closer.

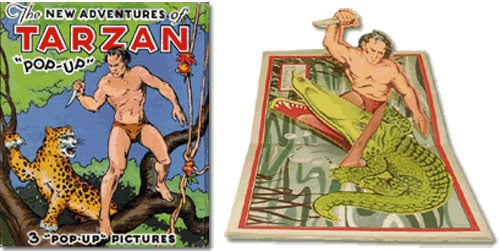

Finally, in the early 20th century, just after we took to the skies, our books finally jumped to stake their claim along the z-axis. The term pop-up was coined in the 1930’s by Blue Ribbon Press, replacing monikers like “Stories with Pictures That Spring Up in Model Form.” And while they were occasionally coaxed by tabs and other manual manipulation, it is more common, and more satisfying, for pop-ups to pop up by the action of opening the book, or turning the page. The mechanism of the book itself became the engine of the pop-ups’ activity, suspending one more level of disbelief above the page.

[Burroughs, Edgar Rice. The New Adventures of Tarzan “Pop-up.” Illustrated pop-up ed. Chicago: Pleasure Books, 1935. A Blue Ribbon Press book. Illustrated by Stephen Slesinger]

[Ricky the Rabbit, Vojtěch Kubašta, 1961]

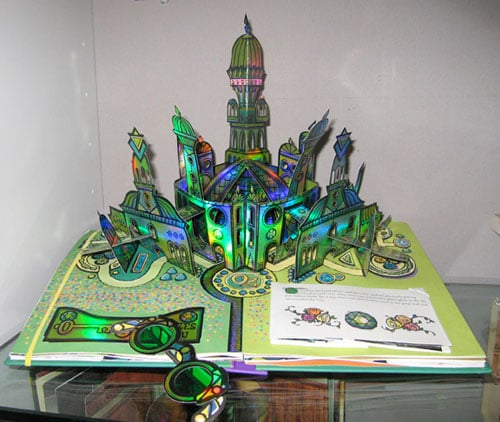

[The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: A Commemorative Pop-up, illustrated by Robert Sabuda]

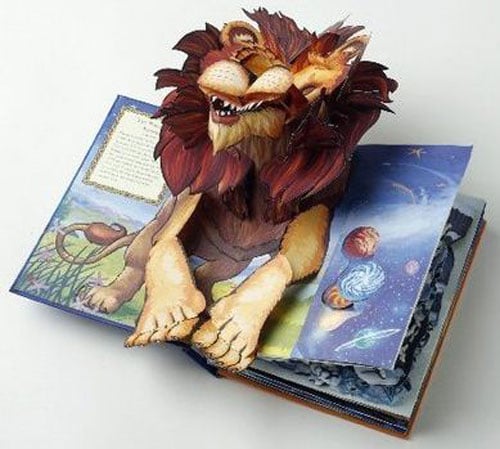

[The Chronicles of Narnia Pop-up, illustrated by Robert Sabuda, Matthew Armstrong, and Matthew Reinhart]

But despite the long gestation, the instantiation of the pop-up had been implicit in the printed word. Even before advent of the codex, which eventually supplied the necessary mechanism in its binding and opening, the z-axis is essential to any kind of reading along a plane. Your eyes are not down there in Flatland, wrestling As and Bs as you bogsnorkle through them to Z. Your eyes are above the reading plane, triangulating the copy into comprehension and communication. And from the apex of that tower you may compile or compress the signal so received, sending it out toward other receivers, in other spaces, or other times. The pop-up leaps up to join you there, for a moment, at play in the fields of the word. The body has met the signal in the book. Sure, the pop-up is a toy. But eventually, might it join us in flight? As our signals zoom out towards other galaxies, one wonders if in part, it already has.

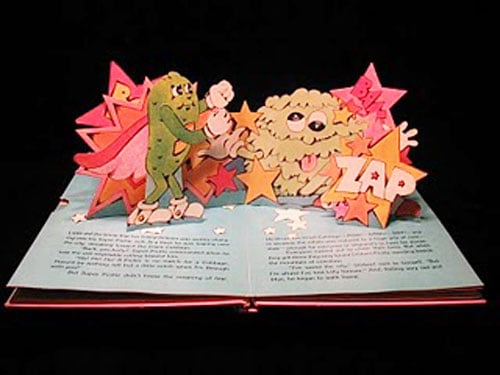

So if Super Pickle is the apotheosis of our centuries-long romance with the codex, and even further back, with the written word itself, isn’t it worth backtracking to take another look at where those signs might be pointing?

Well . . . yeah.

[The Adventures of Super Pickle, by Dean Walley, illustration by Mike Strouth, paper engineering by Dick Dudley, 1972]