Snowbound

By:

February 1, 2011

[Sign]

Like many residents of Anyplace I had put off seeing the nearby Resident Attraction, simply because it was just up the street. But moving plans shifted my definition, and as a soon-to-be Not-Resident it warranted a visit. Conveniently, there’s been no shortage of Scenic Blizzard Photo Opportunities, so I and my phone ventured out to the cemetery.

[These photos are now from 3 blizzards ago, during which the scenery has gone from basic to scenic to basically invisible, as snow pushes the brightness slider all the way to the right.]

[Not monks]

[Outline]

[Glitch]

[Obelisk]

[Face]

The battery-indicator on my iPhone is a bit of a trickster and had been indicating its satiety for two days, which should have given me pause, but instead I believed it. Which belief led directly to its running out of juice about 20 minutes in.

I hate going backwards, so it wasn’t an option to go back in and recharge it. I was out, and I was staying out. I decided to have an experience, rather than record one — not that I think that’s necessarily a better option, just a different one.

Besides, it had occurred to me, and not for the first time, that the photos (mediated through the tiny lens and tinier 1s and 0s, but unaugmented with any additional apps) were not really capturing what I saw.

[details, ancient and invented words, Civilization Landscape Series by Qin Feng, 2009]

Because what I saw was spectacular.

I like cems, especially garden ones. My favorite is Highgate in London, in which the now-overrun vegetation is nature as cultural signifier: one of post-WWII neglect and shifting fashions in interment, and also of our Poe-inflected, retro-gothic view of 19th-century urban planning.

[Highgate cemetery in summer]

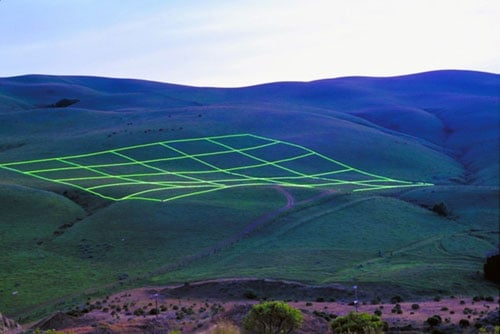

But I also like the cemetery grids of Flanders and Gettysburg, in which a Cartesian rationality is drafted on top of not-quite-flat-but-at-least-not-overgrown fields, in an understandable, and understandably futile, attempt to give some order and meaning to massive, mechanized death.

And I like quite other kinds besides, from the Art Deco’d crematoriums of the Hollywood Hills to the La Brea Tar Pits. But at any rate, Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston, designed by (Henry) Alexander Dearborn, who also designed the slightly older Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts (itself modeled on Père Lachaise in Paris), slots easily into the first category of garden cem. It’s an art-directed sculpture park, its rolling hills and overhanging trees parsed by wandering lanes, in which a series of human-sized tableaux of branch, font, marble and iron present themselves. The trees are towering and various; the details, numerous and baroque. Everywhere there is something for the eye to rest on, and feel one’s self consequential or in-, or just lucky to be able to wander through and absorb of it what one can.

[Snow angel]

[detail, Nine Dragons by Chen Rong, 1244]

Which is how I tried to appreciate it once the photography part of my field trip was over. I have suggested here previously that maybe photography’s claims on realism have come full circle, leading photography towards gesture, and us back to experience, not qua experience necessarily, but as a visual aesthetic. Even with a good camera, or a fisheye lens, or High Dynamic Range adjustments after the fact, the images still would not have really have captured the essence of the scenes, which is of course a feeling.

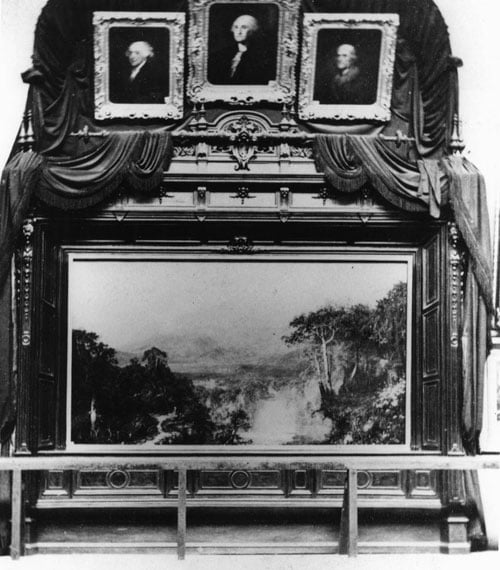

They may be ok, or they might have been better, but a realistic landscape photograph is different from a kiosk backdrop in the drugstore . . . how? Or perhaps they might aspire to the seamless clarity — of a motivational poster. A painting might have been even worse. What are the options, to copy Corot? Or Bierstadt, or even Wayne Thiebaud? All those approaches have merit, but the merit lies not in their reality.

[Mountain Retreat, Bob Ross]

Besides, they’ve all been done. No, an accurate painting of a scenic view risks filling up with “happy little trees:” an image with nothing wrong with it but also nothing in it to see. Hundreds of years of art history and technology have booted us back out into the landscape itself. It doesn’t mean we can’t like landscape representations. But they’re not realism. They’re performance.

[The Heart of the Andes, Frederic Edwin Church, 1859; as displayed in 1864]

Stylization is not necessarily bad, nor backwards. In camera apps one sees an interpretation of photography as an aesthetic practice, rather than only, or even, as a record of reality. But also, some visuals require immersion, and resist imprisonment in x and y. In nature, as well as art.

[Luminous Earth Grid, Stuart Williams, 1993]

[detail, UTOPIA Project, Olafur Eliasson, 2010]

[028 by Gerco de Ruijter, 2008-2010; as featured on BLDGBLOG]

So, do I need new batteries? A new app? New eyes? Yeah, probably. But in the meantime, I am happy to report that the experience performed quite well. I recommend catching the show.

[Chinese Paintings from Fresh Ink: Ten Takes on Chinese Tradition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, on exhibit until February 13, 2011]