Feedback (10)

By:

December 17, 2010

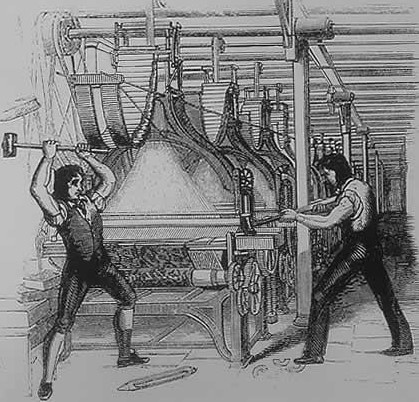

FEED (December 17, 1999): The original Luddites missed their target. They “acted like bulls, hypnotized not by the flashing red cape but by the whir of machinery,” lamented political philosopher Sebastian de Grazia in his 1962 study Of Time, Work and Leisure. “All the while the real enemy, the matador, was there behind, silent, imperturbable: the clock on the wall.” So it’s not “technology” which makes us less human, de Grazia argued persuasively, but clock dependence; that’s why “the free professionals today are envied, because their time is not clocked off like industry’s.” Likewise, in Keeping Watch: A History of American Time (1990), historian Michael O’Malley predicted that computers, fax machines, and telephones would one day make office work at home a realistic possibility, thereby moving society “away from clocks and watches and back toward nature’s example.” Unfortunately for the hopes of these thinkers, a report in the Boston Globe’s business section this week suggests that “free professionals” may never again be off the clock.

This is the tenth in a series reprinting FEED Dailies written by the author in 1999-2000.

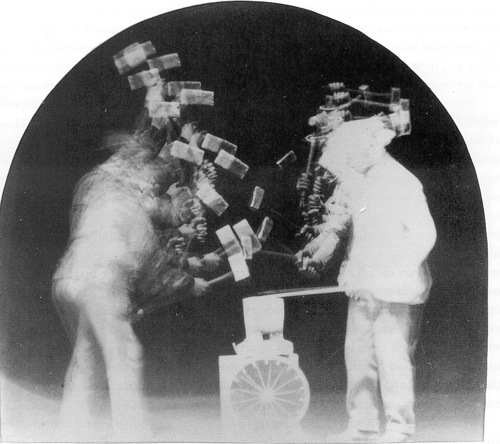

Two Massachusetts companies are racing to produce the equivalent of time clocks “that can keep track of you wherever you might be,” the author of the Globe article reports enthusiastically. Responding to a work force increasingly composed of contractors, part-timers, mobile workers, telecommuters, and home-based workers — many of whom have opted to work off-site because they long to proceed at their own pace — companies like Kronos, Inc. and Simplex Time Recorder Co. have developed systems which “extend” out to the individual employee. Kronos, for example, advertises a suite of products and services providing “solutions that touch every facet of the employee’s workday, and offer senior management visibility to performance across the enterprise.” Translation? You can run, but you can’t hide.

By the 1910s in this country, the pre-eminent time-and-attendance office equipment company was the International Time Recording Company (later known as IBM), whose catalogues warned employers against “evanescence” — time’s fleetingness. Around this same time, Frederick W. Taylor, the father of scientific management, helped pioneer techniques by which employers could capture basic labor data, and transform it into information that could “improve work force productivity and the utilization of labor resources.” This last phrase comes not from Taylor, however, but from Kronos’ website, which promises to help managers know exactly which jobs its so-called free professionals are spending time on, as well as how efficiently those jobs are being performed. Thanks to applications which require, for example, that employees who work off-premises dial in the start and stop times for each and every task they perform, Kronos and Simplex (a company founded by Edward G. Watkins, one of the first time-clock patent-holders) have extended Taylorism to its final frontier: the home office.

In a way, this development is actually a good thing. When Situationist Guy Debord wrote in The Society of the Spectacle that the rich occupy “historical” time, in which new things can happen, while the poor are constrained by “cyclical” time (the sweep of a clock’s hands), in which the same things happen over and over again, he never meant to imply that off-the-clock telecommuters enjoy the “lazy liberty” of the rich. But well-meaning theorists like O’Malley and de Grazia, by suggesting that those of us who aren’t directly subject to clock time are somehow exempt from discipline, surveillance, and control, have contributed to this illusion, haven’t they? So let’s thank Kronos and Simplex for reminding us that even if the staunchest freelancers among us had temporarily escaped the clutches of Taylorism, no one who works for a living is ever really free.

Launched in May 1995, the web magazine FEED — which helped launch the careers of Steven Johnson, Steve Bodow, Keith Gessen, Joshua Micah Marshall, Erik Davis, Christine Kenneally, Alex Abramovich, Chris Lehmann, Sam Lipsyte, Alex Ross, Clay Shirky, Ana Marie Cox, and many others, including yours truly — went offline in the summer of 2001. In June 2010, its archives were made available. This is the tenth in a series reprinting a few of my own favorite FEED Dailies.