Of Age

By:

December 6, 2010

There’s an undeniable romance in discovery, at least from the armchair’s perspective. Sunk into the leather chair, feet slippered upon the ottoman, with a nice shot of Oban and a roaring fire (or so I imagine), there’s nothing better than to read about journeys to the ends of the earth. Just how awful is it, in all its excruciatingly vivid detail? Can they persevere? What will they find? Who will live to tell the tale?

Meanwhile, the adventurers themselves were rewarded with: rocks. A lot of ice, and rocks. Bad weather, and rocks. A lack of atmosphere, and rocks. Doubtless more adventuring further from earth will yield more of the same.

But back here, we’ve more or less covered it all. New feats of discovery now sound a bit arbitrary and silly: the second Slav to swim the Amazon, the youngest person to stand at the South Pole, the third set of triplets to cross the country on pogo sticks . . . while these may represent significant efforts for the various real or hypothetical individuals pursuing them, their relevance to society at large is whimsical, existing only in relation to the niche consisting of their (real or hypothetical) competitors. The peaks have all been bagged, if you will.

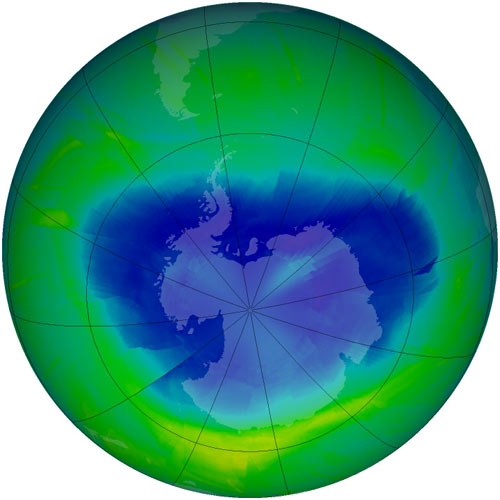

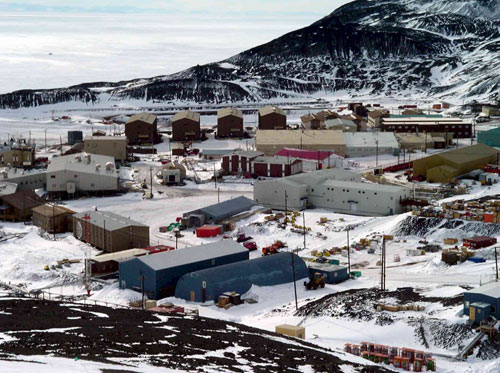

At the close of the Heroic Age dawns the Age of the Commute. We plant the flag, then we go back and see what can be made of it — are any of those rocks diamonds or gold? Or uranium, perhaps? We scour over and around and under it, looking for “resources” or anything that can be defined as such. Animals, plants, fossilized animals and plants . . . oh, yes, of course there’s science. They can measure all those rocks, or the empty space above them.

At any rate, what begins is business. More and more of us travel to the spot, either to work onsite or to retrieve things to work on. And then more of us come as tourists, or as athletes, hoping to somehow re-enact aspects of our predecessors. Industries grow up around the various activities, in addition to the normalization of transport to and fro. In the hubbub, romance sneaks out the side door. And much as we try to conjure it while sitting around the meal tent, it’s nothing we can grab onto; those are only suggestive shadows thrown by headlamps.

But luckily, the Age of the Commute does not signal the end of Ages. Following the Age of the Commute is the Aesthetic Age, and this is the one we’re in. After peak-bagging and rock-measuring comes: running around in circles? Yes! Marathons in exotic places; there is not a continent that does not host its own.

And art projects — stranded aliens under Antarctica. IMAX on Everest. Tap-dancing on the moon! (Well, eventually.)

[Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding, dir. Stanley Donen, 1951]

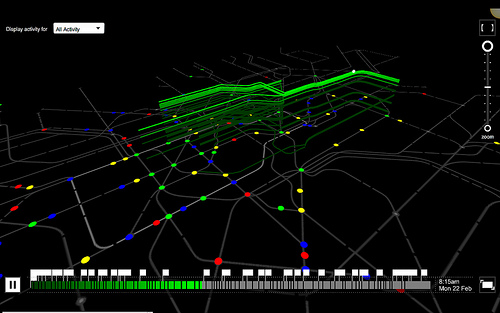

Back in app-land, the social/locational game Chromaroma reframes our parent Age by gaming the commute itself. Users of the London Underground are encouraged to win points and compete against their fellow commuters — not for higher wages or the corner office (their usual game), but for exploring their city and visualizing beautiful data by drawing lines with daily trajectories.

This apotheosis of the absurd does not mean our Age is Small. Absurdity can be a response to as well as an expression of the existential dilemma. There’s the absurd and there’s The Absurd, and each is the other. Why are we here? Why do we live, why do we suffer? Those are not the right questions, but we keep asking them. And absurdity is a way of running in circles around the event horizon of the Absurd (faster! longer! through Death Valley! on Antarctica! etc.).

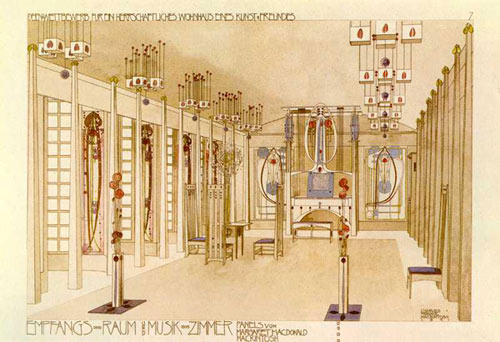

The Aesthetic Age had its anticipation in the Arts and Crafts movement of the turn of the last century, which emphasized combining form and function, and advocated the infusion of art into everyday experience, or at least into everyday objects. And fonts. But our Aesthetic Age takes this one step further. It’s not only the surfaces any more, it’s the experience itself that is to be mined, or détourned, for aesthetic value. As Chromaroma suggests, the performance of the function can be a performance, if approached in the right way.

The great discovery of our Age is: it’s not what we can discover, it’s what we can make of it. And this making-of is an open-source, democratic creativity. The playfulness is necessary to get us thinking outside of boundaries long etched in our assumptions. And in the play of imagination and the redrafting of boundaries, we might create new worlds. The ones the next Age might discover.