GET THE BEAR HORN, MIKAH

By:

December 4, 2010

Modjeska Canyon, in the foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains, where Stanford White built the great Polish actress Madame Modjeska a home in 1888, has been settled for a relatively long time by the standards of Southern California. People that live here tend to introduce themselves by saying how long they’ve lived in the canyon, a kind of instant verification that they, presumably like you, are not of the gated community big box strip mall tribe over the hill. Last week a tree fell across the one road out of the canyon, and no one could leave. The atmosphere was almost festive. The place is laced with coastal live oaks and prickly pears and massive bushes of Jade plants. There’s a bird sanctuary at the end of the road. At night it’s actually dark. Silverado, the next canyon over, is the site of the old Silverado mines, the post office, a one-room library, an understocked convenience store where you can buy things like boxes of band-aids with no band-aids in them, and the Silverado Cafe.

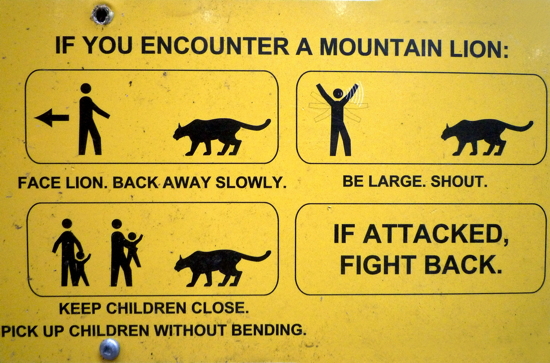

At the end of Silverado Canyon Road, going into the Cleveland National Forest, signs advise you to pick up your children and dogs if you see a mountain lion, to appear bigger, and they also advise you to fight back. Last night, while our neighbor was flashlight scanning a nearby tree to figure out what unusual visitor was making what uncustomary noise, I talked to his wife about mountain lions. There were attacks in a nearby park a few years ago. Yeah, she said, one of the bikers got eaten.

The lease we signed to live in Modjeska acknowledges that we live in “a wilderness area posing risks including but not limited to fires, floods, mudslides, earthquakes, downed power lines, closer roads, high winds, cactus, poisonous place, the presence of harmful animals and insects including but not limited to spiders (black widows, tarantulas, etc.), snakes (rattlesnakes, etc.), scorpions, mountain lions, coyotes, raccoons, possums, mice, hawks, and other dangerous animals and insects.” Also we agreed not to climb the trees. So far we’ve seen a rattlesnake and two tarantulas, and heard a coyote.

There are standard objects of fear in any upbringing: child kidnappers, dim stairwell rapists. Rural life introduces cosmical fear. Cosmical fear is different from human fear in its boundary lines, but also in scale. To fear a human is to fear something more or less as powerful as you. Humans afraid of the more than human try to gain a sense power through technology. But cosmical fear is a fear you submit to, experienced without the cordoning or mitigating benefits of invention. It is rude, and shocking, and good, and relatively hard to get in Brooklyn. Whatever Bruno Latour has to say about nature — that there’s no such thing as the outside, that we’ve never been modern, that the problem of where to put the trash should let us know all these things — there is at least a way in which we make ourselves feel that nature is out there, and that the problems of, say, big cats, are excluded from the standard American life.

Cosmical fear is something I learned about from Ralph Waldo Emerson before the mountain lions took over my field education. He wrote: “Crossing a bare common, in snow puddles, at twilight, under a clouded sky, without having in my thoughts any occurrence of special good fortune, I have enjoyed a perfect exhilaration. I am glad to the brink of fear.” This kind of rare perception is a function of those Emersonian moods that undo categorical boundary lines. It’s the translation, in a religious temperament, of the same impulse that underwrites the creaturist strand of post-humanism, and it seems to me that the exploration of the vague boundary between human and creature is a good place to take it up.

Martin Heidegger is a bit of blur for me but one thing I remember he said within the larger project of divinizing our magisterial scaffold of concepts called language, is about animals: Only man dies, he says, the animal merely perishes. Cosmical fear calls the bluff of this binary. To fear cosmically is to acknowledge that humans die and also perish, possibly by being et up by a mountain lion. It’s like what Mac Wellman says about plays: they go on for a while, then stop.

Here in Southern California, where pop-up towns creep toward the mountains, the mountain lions occasionally show up in town. A tracking project has been catching and fitting radio collars to mountain lions to map their wandering range, to figure out where and how they cross freeways, and what kind of corridor space they need out there, if we were to treat them not as something we can eulogize the nobility of after we’ve eradicated them, but as part of the same world that is in here, continuous, just like In-N-Out tutors.

Once I was walking in the snow in the woods and a fox ran out, and he stopped and looked me in the eye. I’m sure it was momentary, but it was the kind of experience that doesn’t have any timekeeping in it. I told a guy who lived around there and he said to me: you’re lucky. They don’t show themselves to people very often.

In the space between them as menace and us as menace, there’s a potential equilibrium, the encounter. The collected wisdom on the encounter seems to be amassed in children’s animal movies, and the lesson seems to be: an animal has a face, so try looking at it.

For example in the Black Stallion, Alec and the Black meet by staring — skip to 6:33:

And later in the Black Stallion, Alec meets a snake, another encounter with the face of the other:

And in non-fiction America, a mom and her kids face a mountain lion. It wants to be one of those things without timekeeping, but anxiety intrudes. After a serene four or five minutes, mom rejects the cosmic in favor of the technological. “I want you to get the bear horn, Mikah.”

“Patience and patience,” counseled Emerson, “we shall win at the last.”