Spacetime Bandits

By:

October 18, 2010

Where you are depends on when you are.

For example, are you lounging with a latté in Battery Park, waiting for the ferry so you can take in a little nearby history? Or are you fighting for your reality, trying to prove you aren’t just another Ape’s Construct after failing the Turing Test while your peers were struck mysteriously mute?

It all depends on what you have time for. And these days, the answer is, not much.

[Textman, Jane Prophet, House of Words exhibit, Johnson House, London, 2009]

I’ve suggested in a previous post about vaudeville that earlier eras have felt themselves similarly pressed. For another example, we might consider Dr. Samuel Johnson. Johnson never stood in front of a microwave willing it to hurry up. And yet he filled his tiny houses with a moveable feast of friends, apprentices, and hangers-on; he filled his writing with the week’s froth of memes and gossip, and while he was at it he decided to trace and organize the definitions of every word of the day, making him think twice about every syllable. To say nothing of the daily 18-plus cups of tea with which he agitated his brain. Yes, Johnson managed to think deep thoughts and accomplish work of substance. But it wasn’t for want of distraction.

There’s a fascinating recent trend in art about place that takes an almost fractalized approach to size. By scaling the work down — way, way down — it turns out that it has as much potential for complexity and meaning as the previous era’s scaled-up offerings. One might call it locative art, or walking tours, but the trend encompasses more than text and audio, and involves more than virtual incursions into physical environments, or GPS. And it turns as much on time as it does space.

[Uchronia/“The Waffle,” The Uchronians, Black Rock City, 2006; photo by George Hart]

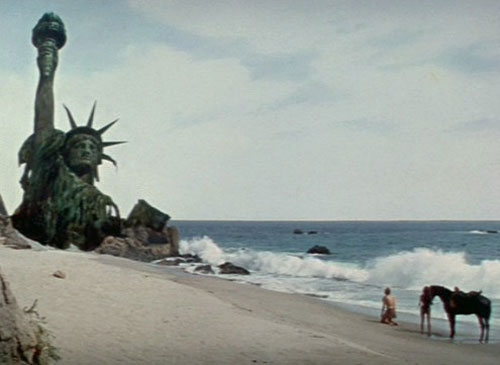

Consider any piece of large, public sculpture, from Spiral Jetty to the Statue of Liberty. Despite these works being outdoors they maintain “white gallery walls” around them, by which I mean they are set apart from the everyday flow. Physical space needs to be assigned, but so does mental space, and for that one needs time. Time to get to where they are. Time to walk around them. Time to allow for contemplation.

But what if walking-around time was itself permeated with smaller stuff?

[The Cones Project, Peggy Nelson, Boston, 2009]

In my recent work, I’ve used randomized audio files (The Audio Tour, 2006), 2D barcodes, cellphones, and Wikipedia (Web021…, 2007), Twitter (In Search of Adele H, 2010), and traffic cones (The Cones Project, 2009) to insert small, short fragments of artworks into the everyday, with their accumulation adding up to much larger and longer-term projects than if the whole of each had been presented at once. The Audio Tour was originally installed to trace the endless Black Rock desert in breadcrumbs of sounds and ideas. In Search of Adele H was a 10-month movie/novel/reenactment on Twitter, in increments of a few seconds a day.

[The Audio Tour, Peggy Nelson, Black Rock City, 2006]

Significantly difficult to display or perform in traditional art-world settings, these incursions into place, like graffiti, live outside the galleries (and outside their funding structures), but inside one’s everyday paths, whether on sidewalks, on the playa, or online.

Locative art can allow art to escape its special-status designation and permeate the quotidian world, giving it potentially greater accessibility. You don’t need to make a special trip, or set aside time. It’s not only that there’s street art, or public installations (legal or illegal), or mimes in corners, or software mapping mashups — it’s that they can be and are inserted into the micromoments in between multitasking, absorbed and contemplated in between errands, caught in a glance before ducking into the convenience store, heard in a snippet on the short walk from the parking lot to the office. Size and duration are crucial to delivery, and in this case, small, in its flexibility, is beautiful.

Small need not be insignificant, however. Small may increment, and herein lies its power. Fragments need enough internal consistency so that they might seem to go together, and enough external differentiation so that we notice their signal winking out from the general flow.

We are pattern-making, and pattern-perceiving, animals, and we strive to connect: the dots, the gaps, the space between us. When not continually told to Obey Giant, we begin spinning our narrative threads, rolling them in spindles or weaving larger webs, as community and inclination permit.

[Giant Obey Giant poster, Shepard Fairey, Venice, 2009]

But sometimes mere repetition is the message. Like so much in new media art, the original impulse might be traced to the military: Sputnik’s A-flat beep is the poster child for the pulse. Calibrated to be detected by American ham radio operators, the signal said, “We are here, we are here! — and you are not.” Them beeps was fightin’ words in the Cold War.

And yet, we crave interruption. Increments accumulate over time, but we don’t have time to stand there and watch them. How many times have you skipped the video installation in the museum because 5 minutes was just too much?

Discontinuous accumulation is the key; the gap is what leads us into this art. Messages arrive to be read or listened to at your leisure. Streams update and can be stepped in more than once. Personal expression fills peripheral spaces along your regular path. A notice pops up on your phone: “Reply? Close?” You need stop nothing you’re doing for these signals to start seeping in. And if the proto-narrative or visual collation is compelling enough, you may even start seeking them out.

In accumulation, small signals may form, if not a presence, than a pressure in the day, a direction, a bent to one’s life.

[Neal Cassady and Timothy Leary on Further, 1974]

And if not? Then we disappear round a corner, and are gone.

Follow Peggy Nelson on Twitter: @otolythe.