Feedback (6)

By:

October 15, 2010

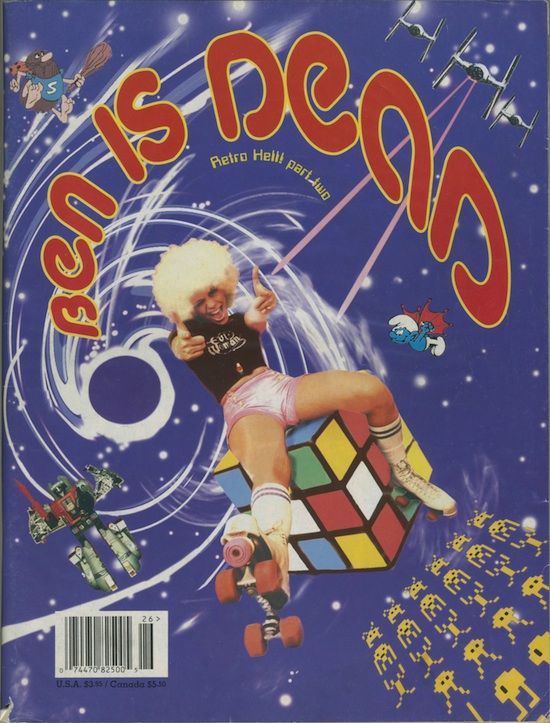

FEED (October 15, 1999): “You don’t have to like or subscribe to the mainstream to find yourself caught up in the desire for acclaim,” explained Darby Romeo, the editor of the long-running zine Ben is Dead, in the publication’s recently released final issue. Romeo was speaking generally about celebrity, the latest and final theme her publication has tackled (in typically obsessive eight-point type, with over 150 newsprint pages, largely devoid of white space). But as always she was also talking about herself. Romeo, you see, believes that publishing something she wants to read is the whole point of being in publishing. In a world where each issue of every newsstand magazine is pre-market-tested to death, such unflagging dedication to self-obsession has garnered her plenty of acclaim. So what does it mean, after 30 issues in almost 11 years, that Ben is Dead is finally dead?

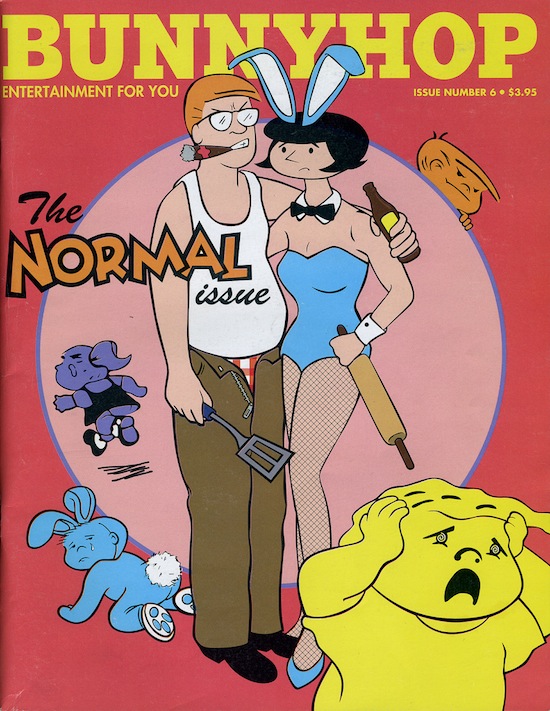

Ben is Dead — whose amphetamine-fueled coverage of everything from disinformation to ’80s pop culture, not to mention all things Sassy, should earn it a prominent place in any encyclopedia entry for “zine” — is the canary in the coal mine of the moribund “zine revolution.” If it goes under, its compatriots probably will, too. Those few naifs who still think self-publishing has any value whatsoever are doing their thing online now, where production and distribution costs are low, and where one’s chances of being discovered (and recognized for one’s efforts) are even lower. As long as there are Xerox machines and glue-sticks zines will always exist, but the few stalwarts who’ve struggled to raise production values by selling ads and printing glossy color covers are rapidly disappearing. Moreover, the dinosaurs who edit attractive and intelligent borderline zines like Bunnyhop, Mommy and I Are One, Giant Robot, and Bust just don’t seem to realize how extinct they already are. [NB: I was struggling to continue publishing Hermenaut at the time I wrote this, so I was indulging in a little black humor at my own expense, here.]

Traditionally, high-performing self-publishers like Darby Romeo have staggered forward against the gale winds of corrupt and bankrupt distributors, a seemingly infinite number of bounced checks, and a reading public barely interested in Granta, much less Bananafish. These crusaders have been fueled, more than anything else, by a shared contempt for the world of glossy newsstand magazines. “It’s so easy to throw a mainstream magazine away,” Romeo said in a phone conversation, “because they’re all just trying to fill a space, one they think will generate money. I don’t ever throw zines away.” True, figures like David Eggers, an ex-editor of both the independently-published Might magazine and mainstream Esquire, have become increasingly adept at keeping fingers in both pies. (Eggers appears twice in the current issue of The New Yorker — once as the wacky self-publisher responsible for McSweeney’s, and once as a respectable memoirist.) But Romeo aims for a different combination of recognition and independence. Though she yearns for acclaim — and she has, in fact, been temporarily famous for masterminding the one-shot I Hate Brenda newsletter — she’s never been interested in mainstream approval. That’s why her next project is, yes, another zine: but the old-fashioned kind this time, the kind where you get a friend at Kinko’s to run it off for you after hours.

To outsiders, zines seem hedonistic, for too many zines are dedicated to sex, drugs, and Royal Trux. But for true believers like Romeo, zine-publishing is hedonistic only in the strictly philosophical sense: While publishing a well-written, well-edited, well-produced zine won’t necessarily help you achieve pleasurable goals in your life, the activity of self-publishing is a pleasurable end in itself. Maybe that’s why, when asked to describe Ben is Dead, Romeo says, “It wasn’t a ‘music magazine’ or a ‘pop culture magazine,’ it was 11 years of my personal growth. It was me wanting to die only after having made a magazine because it was the best way to save my life at the moment.”

Launched in May 1995, the web magazine FEED — which helped launch the careers of Steven Johnson, Steve Bodow, Keith Gessen, Joshua Micah Marshall, Erik Davis, Christine Kenneally, Alex Abramovich, Chris Lehmann, Sam Lipsyte, Alex Ross, Clay Shirky, Ana Marie Cox, and many others, including yours truly — went offline in the summer of 2001. In June 2010, its archives were made available. This is the sixth in a series reprinting a few of my own favorite FEED Dailies.