De Condimentis (4)

By:

October 9, 2010

Fourth in a series of posts revealing the secret history of condiments — and the influence they’ve had upon the course of history.

How to account for the curious popularity of hot sauces? It’s not that they taste “good” — at least not in any conventional sense of the word — and it’s not really that they make food taste better, because so often what they really do is make food taste like hot sauce. Chiles used as a seasoning in a well-rounded sauce — be it a Thai curry, a Mexican mole or a Neapolitan puttanesca — are one thing (and for the record, the stewed, spiced, meat-and-beans dish popular in Texas is called chili; a chile is the pepper itself, plain or prepared). But chile as a condiment: why do we do it to ourselves? When faced with a perfectly lovely plate of eggs, why reach for the tabasco? When imagining a hot dog for lunch, why does it always have sriracha on it? The eating of chile sauce is curiously, undeniably attractive. But why?

In the Aztec world, the chile was an ingredient in almost all recipes, helping to flavor a corn-based diet that was conspicuously lacking in variety. The lords of the Aztec empire ate turkeys and rabbits, chocolate and lobsters, but the people ate corn. Keeping a sprawling, protein-deficient empire afloat was made easier by the ubiquitous, pleasing chile (plus there’s a notion that it goes really well with human flesh). It also made its way into a variety of ceremonies, and is noteworthy for being the key element that kept the Xolotl, the monstrous canine champion of deformities, twins, and Aztec baseball, at bay. The chiles bred by the Aztecs, like the chiles eaten today, were from two major families of the genus capsicum — chinense (the habanero and Scotch bonnet peppers) and annuum (representing the rest, from bell peppers to jalapeños). In the Florentine Codex, a post-colonial documentation of pre-colonial Aztec life, 4 types of chile peppers are mentioned: yellow, red, green, and small, and they are noted as hot or not, giving 8 types of chiles. Some things were served with multiple types of chile, some with only one – Turkey was served with all types, frog only with green chile, newt with only yellow, tadpoles with only small chiles, and grey fish with only red.

Some have suggested that the endorphins released as our bodies respond to the painful heat of the chiles are so pleasant that the compulsion to put hot sauce on our food is nothing more than a species of addiction (opiates and endorphins are structurally identical). Psychologist Paul Rozin has suggested that eating chiles is an example of a “constrained risk”: like riding a roller coaster or bungee-jumping, it can be enjoyed because although it’s frightening, we know it’s not potentially lethal, and the thrill of the fear can be enjoyed without repercussion. What has long been clear is that there is something at work beyond the gastronomical when we eat a chile — something transformative. Our feelings change, our view from out of our head shifts, slightly. Eat a nacho piled high with jalapeños or a hamburger drowning in New Mexican green chiles, and you’re not precisely the same person afterward.

It’s long been said that “you are what you eat”, but as the 2nd century physician Galen found, it’s more that that you are WHO you are because of what you eat. This is axiomatically more problematic, sure; but, building on theories developed by Aristotle and Hippocrates, Galen gave us a fully-formed view of the four humors that describe human behavior — and also proved that the biles are not in food, but only influenced by food. Galen argued that each one of us is ruled by a specific humor: blood (sanguine), yellow bile (choleric), black bile (melancholic) or phlegm (phlegmatic). In the millennia since, many researchers have attempted to chart the characteristics of each humor, from Kant (who believed melancholics to be warrior kings and phlegmatics to be serial killers) to Myers/Briggs (who sought only to torture job applicants). The simplest and most useful scheme, however, are the hot/cold and moist/dry dichotomies:

Sanguine: warm and moist, the Spring humor — courageous, hopeful, amorous, irresponsible.

Choleric: warm and dry, Summer — easily angered, bad tempered, ambitious.

Melancholic: cold and dry, Autumn — despondent, sleepless, irritable, Introspective, sentimental, gluttonous.

Phlegmatic: cold and moist, Winter — calm, unemotional, sluggish.

The 11th-century Muslim physician Avicenna laid out food prescriptions depending on which dichotomy you are ruled by. With the notion of keeping your humors in balance, you need to eat the foods opposed to your humor; if you’re sanguine you should be eating foods that are cold and dry, etc. In the middle ages, there was an entire cottage industry of “doctors” prescribing meals for rich folks based on the humors. Until the 17th century, cookbooks and medical books were the same thing. This died out as modern medical techniques began to predominate, but, ironically, it was at this moment that the doctors should have been most aggressively prescribing food-based cures. Until Europeans reached the New World, peppery spices were limited to black pepper, long pepper (a Javanese fruit similar to black pepper), and melegueta pepper (or grains of paradise) — none of which pack the gustatory punch or endorphin-tweaking, humor-influencing powers of the chile pepper.

There have been scattered events through history that suggest that individuals and small groups have noted the transformative effects of chile peppers, to wit:

November 8, 1519: Montezuma’s first action on the arrival of the conquistador Hernán Cortés is to send him food spiced with chiles in hopes of turning his aggression into friendship. When this failed utterly he exclaimed “In great torment is my heart; as if it were washed in chile water, it indeed burneth.” And Montezuma knew what chile water on hearts was like, for it was customary to serve the hearts of enemies of the Aztecs with a chile sauce.

Meerut, India, May, 1857: 85 native soldiers employed by the British East India company, who had been fed piri-piri peppers for 17 straight days by Lt. Colonel George Carmichael-Smyth, are court-marshaled and marched around the camp after refusing their rations. “no one can eat piri-piri peppers and fail to love me,” Carmichael-Smith reportedly claimed just before the ensuing Indian Mutiny erupted, eventually engulfing northern India and claiming the lives of thousands.

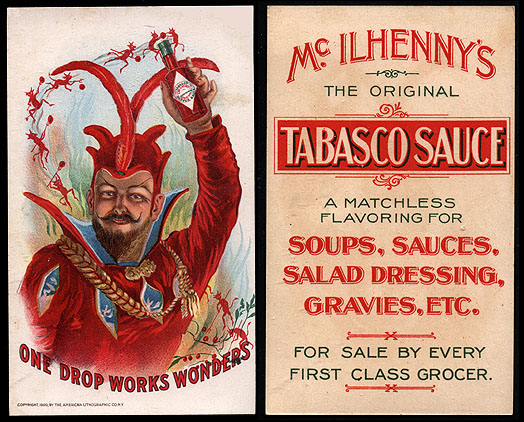

Avery Island, Louisiana, 1858: Tabasco is founded and becomes curiously popular. The chiles for Tabasco sauce are grown on Avery Island, a massive salt dome that attracted the attention of Walker Percy as the setting for his novel Love in the Ruins (1971). In the novel, the main character constructs the Ontological Lapsometer, a device for diagnosing and treating moods, that threatens to cause a catastrophe because of its proximity to the Avery Island salt mound. On Avery Island is also the debut album from the mind control associated band Neutral Milk Hotel.

Algeria, 1962: Using cash raised from the sale of opiated hash in the Southern United States, the Organisation armée secrète attempted to “pacify” the Algerian uprising using imported Scotch Bonnet Peppers to transform the harissa-eating national character from melancholic to phlegmatic. The abject failure of the attempt led directly to the attempt on General De Gaulle’s life (dramatized, more or less, in Forsythe’s Day of the Jackal, though with the chiles conspicuously absent.)

Cape Verde, 1974: the Portuguese Import/Export Company Caixas de Coisas Boas (who, given the pepper’s Brazilian origins, should have known better), to avert a showdown over a chile shortage, shipped 300 tons of melegueta pepper into Praia, thinking it was the locally popular malagueta (chile) pepper. It was burned on the tarmac.

There have been missteps — perhaps there will be more — but harnessing the transformational power of chile peppers is far from impossible. What has always been lacking is a proper framework for their use, a system, both descriptive and prescriptive, that allows the user to see the relationship between pepper and mood, flavor and humor. Though there are hundreds of chile peppers used for culinary purposes, we’ll confine ourselves to the few that are used as condiments. It’s the drive to self-medicate, to keep our humors in balance, that is most central to the human condition — and most accurately indicates the nature of each pepper.

As the Aztecs had it, there are eight types of pepper — a scheme which corresponds to the four basic humors, each with a reversed dominant dichotomy (e.g. dry, hot and hot, dry). Aristotle pinpointed the method for moving between the humors by using the element that the humors have in common — sanguine and phlegmatic share the property of moistness, sanguine and choleric hotness, etc.. By applying a pepper with the shared dominant characteristic, humors can be shifted, even if one’s basic nature is immutable.

[table id=5 /]

As one might expect, some of the characteristics can change based on usage and ripeness. Jalapeños, for instance, which when picked green are naturally cold, aren’t always thus if ripened and smoked (as a chipotle); likewise their giant, tastier cousin, the New Mexico green, can be ripened and dried. The dichotomies given are for their most frequent use as condiments.

This system of Aristotle’s also forms the basis of the transmutative alchemy of the likes of Paracelsus and Newton (“crazy” Isaac Newton, not the better known “gravity” Isaac Newton), though often with the elements (clockwise from top: air, water, earth, fire) replacing the humors. So to move from choleric to sanguine, using the common characteristic of hot, would take the application (noting Avicenna’s warning that foods harmonize with the opposite humor) of a “cold” jalapeño sauce. To move from sanguine to phlegmatic (supposing you wanted to) would take a pequin/arbol chile sauce. We do all of this intuitively, choosing sauces that either harmonize with our base humor, or the sauce that allows us to move to a more desired state – Avicenna called this drive towards self-preservation and balance Quwwat-e-Mudabbira, which translates “healing power of nature” – all organisms seek to heal themselves; even people.

All of this is why the Naga Jolokia pepper (sometimes called the “ghost chile”) is so dangerous. It’s a hybrid between Capsicum frutescens (which includes malagueta, tabasco and thai peppers) and Capsicum chinense (habanero, Scotch bonnet) and thus acts on opposed humors simultaneously — it’s Hot/Cold. Neo-Kantian political philosopher John Rawls once said of the Naga Jolokia that its creation could only have taken place “behind a veil of ignorance.” It was created for its monstrous heat — estimated at four hundred times the heat of a tabasco — but it’s a sower of disharmony, “a destroyer of worlds” as Robert Oppenheimer noted after innocently putting some on his huevos rancheros one quiet morning in Los Alamos.

Hopefully this will serve as a warning as well as an aid — hot sauce has gotten enormously more popular in recent years, and the opportunity to misuse it has grown exponentially. So recognize your humor and recognize that you can’t, like an 1880’s baseball player going from 1st to 3rd across the pitcher’s mound, go across the square — that’s your antithesis. And, even more dangerous, avoid the Scoville scale (the muy macho chile heat rating system) and any of the crazy super “chiles”. They’ve been overbred and are loony and dangerous like a perfectly-spotted Dalmatian. Start eating peppers that have been cross-pollinated with other pepper families for a few generations and you’ll be lucky if all you end up with is a world-class case of Montezuma’s revenge — which, most of the time, is actually a case of incompatible humor reaction.

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.