Bouzingos

By:

October 8, 2010

The following is an excerpt from a post published yesterday about the Autotelic Generation (born 1805-14). Their number includes: Gérard de Nerval (1808), Edgar Allan Poe (1809), and Théophile Gautier (1811).

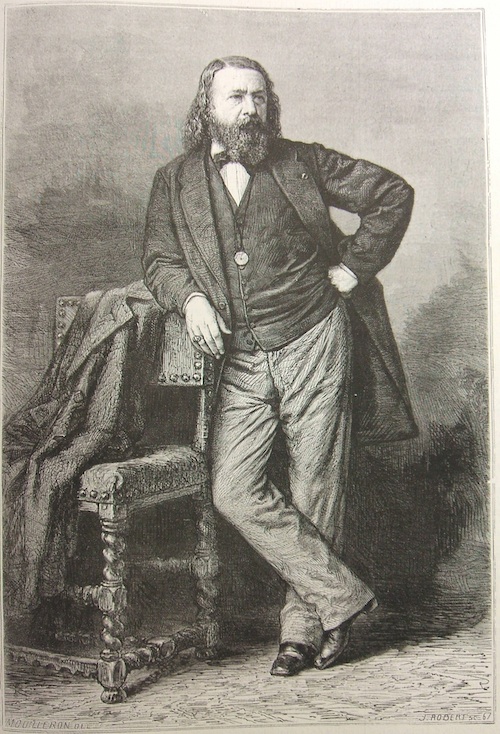

As the literary critic Gene H. Bell-Villada has argued, the idea of l’art pour l’art was particularly attractive to French writers whose medium (poetry) and rhythm of production (leisurely and careful) conflicted with the modes and rhythms of the newly industrialized literary market. He calls Gautier, Nerval, and their comrades “aesthetic separatists” — i.e., they were a crypto-political movement that rejected both the (bourgeois) republican and (hereditary aristocratic) monarchist factions of the era. They were particularly opposed to the newly ascendant culture-consuming bourgeoisie — particularly bourgeois liberals, who insisted that art should be socially and morally “useful” — but they weren’t socialists. The dandies presented themselves as a new, self-invented kind of aristocracy.

“Art for art’s sake” is the English rendering of Gautier’s defiant l’art pour l’art slogan, which expressed the aesthetes’ belief that the intrinsic value of art is divorced from any didactic, moral, or utilitarian function. “Nothing is truly beautiful unless it is useless,” insisted the preface to Gautier’s Mademoiselle de Maupin (1836); note that works like Gautier’s are described as “autotelic,” in the original Greek sense of something “complete in itself.”

In the US, Poe was another theorist of autotelic art — which is why Baudelaire, whose translations did so much to popularize Poe in France, was such a fan. In his essay “The Poetic Principle” (1850), Poe writes:

We have taken it into our heads that to write a poem simply for the poem’s sake […] and to acknowledge such to have been our design, would be to confess ourselves radically wanting in the true poetic dignity and force: — but the simple fact is that would we but permit ourselves to look into our own souls we should immediately there discover that under the sun there neither exists nor can exist any work more thoroughly dignified, more supremely noble, than this very poem, this poem per se, this poem which is a poem and nothing more, this poem written solely for the poem’s sake.

The French Revolution of 1830 (the July Revolution) saw the overthrow of King Charles X of France and the ascent of Louis-Philippe, the “bourgeois monarch.” In Paris during the Twenties (1825-33), political factions (ultra-royalists, Girondin republicans, Jacobin republicans, American-style republicans, Bonapartists, moderate semi-liberal royalists, utopian socialists) enjoyed the support of various literary factions.

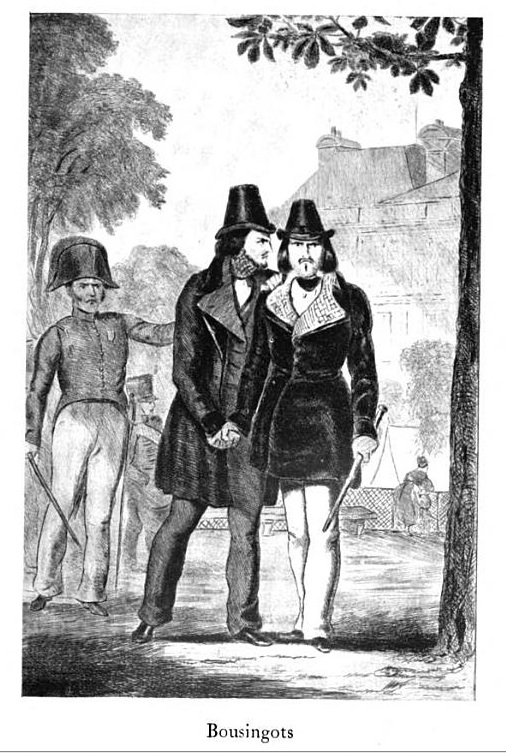

Most romantics were somewhere on the continuum between republican and liberal, though their factions — Les Meditateurs, Les Frénétiques, Les Larmoyants, Les Illuminés, Le Petit Cénacle, Les Jeunes-France, Les Buveurs d’Eau, the literary-political Bouzingos, the militant Bousingots, Les Badouillards, Les Muscardins, Les Dandys and Les Bohème — suggest that the continuum was a minutely parsed one. The Autotelics who interest us are dandies, aesthetes, and Bouzingos [a slang word meaning something like “shit-heel”] like Nerval and Gautier.

The aesthetes’ insistence upon art’s uselessness may have been an anti-partisan position, but it was not unpolitical. The dandies and flâneurs who inspired Baudelaire’s dandyism, and his theory of the “perfect flâneur,” were engaged ironists; their “useless” art and anti-bourgeois mode of dressing and sauntering through crowded Paris streets was a political gesture, a rebuke to the proto-neoliberal “bourgeois monarchy” of Louis-Philippe — which they recognized, presciently, as a new mode of tyranny. Whether or not he actually once walked a lobster on a pale blue leash, Nerval’s flânerie was a form of guerrilla street theater — a gesture of contempt for the hustle and bustle of modern capitalism.

NB: Somewhere in the early 19th century, according to patterns I’ve discovered via research and abductive methods, our decade/generation scheme shifts from a “4-3” to a “5-4” pattern. It seems fairly obvious that the shift happened in Paris, in 1830 — thanks to (a) the “battle of Hernani” waged by the Jeunes-France on behalf of romanticism vs. rules in poetry and proper language on the stage; (b) the July Revolution, which installed the “bourgeois king” Louis-Philippe and signaled the first triumph of the middle class in world affairs; (c) Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, which shattered the convention of “four-squareness” in melody, the rigidity of rhythms, and the predictability of harmonic formulas; and, finally, (d) at the Academy of Sciences, the break between Cuvier and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire over Lamarck’s hypothesis (which chimed with the Romanticist idea that everything is alive and in motion) about the transformation of species, i.e., Evolution. As a result, the the Eighteen-Twenties lasted only nine years: 1825-33.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).

Which means the Post-Romantics are a slightly smaller generation than every other one in my scheme. Those born in a 3 or 4 year after 1825 are cuspers; those born in a 4 or 5 year before 1833 are cuspers.