Novel Apps

By:

September 28, 2010

Dipping into the archives at the lovely web site of the Paris Review, I came across a 1984 interview with J. G Ballard, in which the great dystopian is asked to describe his “daily working habits”:

Every day, five days a week. Longhand now, it’s less tiring than a typewriter. When I’m writing a novel or story I set myself a target of about seven hundred words a day, sometimes a little more. I do a first draft in longhand, then do a very careful longhand revision of the text, then type out the final manuscript. I used to type first and revise in longhand, but I find that modern fiber-tip pens are less effort than a typewriter. Perhaps I ought to try a seventeenth-century quill. I rewrite a great deal, so the word processor sounds like my dream. My neighbor is a BBC videotape editor and he offered to lend me his, but apart from the eye-aching glimmer, I found that the editing functions are terribly laborious.

He describes a lost world.

Twenty years later, Ballard’s work habits had not changed. In an 2006 interview with Simon Sellars of Ballardian, the author said that, although quite interested in computers, he was too set in his ways to try them out.

I don’t have a PC. I’m not on the internet and I think that’s a matter of age. I’m nearly 76 now and I think the personal computer and the internet really came in about 10 years ago. And by then I was an old dog and the internet was a new trick. I mean, I still write my novels in longhand and type them out on an old electric typewriter. I don’t have any modern appliances.

Ballard’s habits mirror those described by so many twentieth-century novelists: the months of steady effort, the diurnal rituals of attention, the epistolary relationship of manuscript and typewriter.

I do have to wonder how real it all was.

I’m thinking about the several senses of the word habit. There is the sense of practice, but also of compulsion, even addiction. But then there’s the kind of habit that’s a raiment, a kind of ritual garb. Maybe it’s the historical tendency of habits go through a cycle with these senses as stages, from practice to compulsion to costume.

Information Architects’ iPad app, Writer, made quite a splash in my corner of Twitter last week.

“Writer has no graphical settings or formatting features,” according to ad copy on the app’s page. “It avoids all distracting glitz in the user interface and puts all the beauty in the shape of the text.” The app also avoids the distractions of auto-correction, spell-check, and toolbars; there’s even a “focus mode” that blurs out all but the three lines of text around the cursor (neurological nota bene: the human brain actually comes with this feature pre-installed).

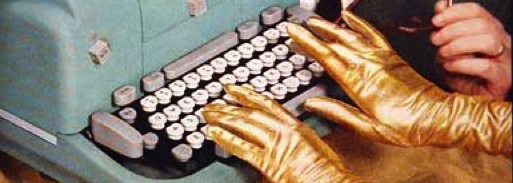

Admittedly, I was rather smitten with Writer at first, although a number of Internet friends found the app’s tendentiousness irksome. But the rub, for me, isn’t its slightly-smug ad copy or its bespoke font, or the suggestion that it will help solve your writing problems. Toolmakers made such claims throughout the industrial era, after all, and writing tools are tools. “Only the Underwood Golden-Touch Electric gives your hands such skill,” goes the copy in a 1957 typewriter ad, “such effortless speed, such print-perfect letters…. It’s as though you’d suddenly put on magic gloves!” We can’t blame the folks at Information Architects for finding a similarly stylish way to pitch their product.

No, I’m struck instead by the setting in which we come to Writer: the world of the app, which militates against every habit of attention and concentration in which Writer wants to enrobe us. Writer is a raiment-stage habit that celebrates the practice-stage era of novel-writing by engineering a cybernetic set of compulsion-stage reflexes.

But this is not a death-of-the-novel post! It’s clear that novel-writing has a lot of energy left in in. Plenty of people have the chops to sustain novel-writing levels of attention, the freedom to write lengthy works, to sequester themselves on islands of concentration. But if there are habits that come with the world of apps, the novels those habits produce will look much different. In the early age of multimedia, James Joyce wrote Ulysses, with each chapter taking on the habits of a different genre of modern prose, from free indirect discourse to vaudeville show to ladies’ magazine.

Maybe the next Ulysses will take the shape of a cycle of apps.

A version of this post originally appeared at library ad infinitum.