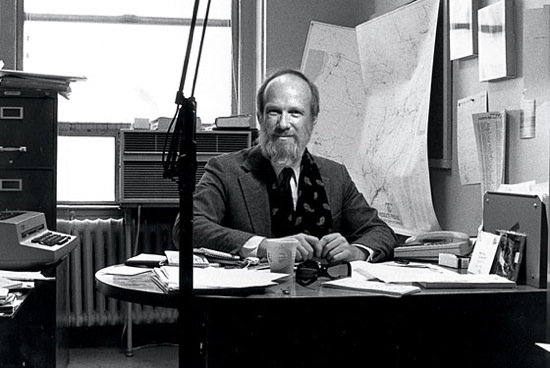

George W.S. Trow

By:

September 28, 2010

On November 17, 1980, the New Yorker took the extraordinary step of devoting an entire issue to “Within the Context of No Context,” an aphoristic essay by GEORGE W.S. TROW (1943-2006). Trow’s jeremiad about the formative influence, via the medium of television and lifestyle magazines, of the “force that seeks to go with the grain” upon the “generation born during (and soon after) the Second World War,” concerns two of this website’s bugbears: Middlebrow and the Boomers. What’s more, and coincidentally, the transitional moments in Trow’s account of Low Middlebrow’s triumph coincide with my own periodization scheme. I’ve suggested, for example, that Low Middlebrow seized the reins of American culture during the Fifties (1954-63); Trow claims that “in 1963… we were still in the 1950s in a way,” and that growing up in the Fifties — he was born on the cusp between the Anti-Anti-Utopians and Boomers — meant being raised less by parents than by “the culture, for reasons having to do with the working of the marketplace.”

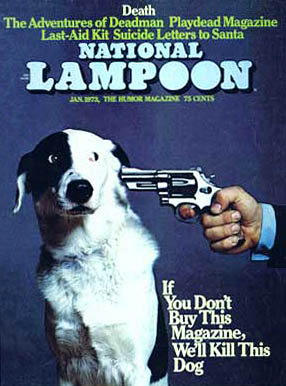

The Sixties (1964-73), which for Trow didn’t begin until the ’64-’65 World’s Fair, and ended shortly before his 1975 revelation that he couldn’t wear his father’s fedora without a “necessary protective irony,” was the era during which the Boomers — a generation formed not by world-historical events (“growth, conflict, and destruction”) but instead by the “organizing power of the context” — failed to grow up. Although the Boomers did improvise their own rock’n’roll adolescence, laments Trow, “they quite rightly considered it the most important historical event of their times and have circled around it ever since.” The perma-adolescence of generational refuseniks like Trow and his friends took a different form: they started the National Lampoon. Their “nego” [nobrow] point of view, Trow says, was: “You’ve got to be kidding.” Among other things, then, “No Context” is an origin myth for Nobrow.

Twenty years before his contemporaries would get around to praising the Greatest Generation, Trow described the the pre-WWI and -WWII generations as “another version of the human race.” Why? They’d been adults, whereas Boomers had redefined adulthood as “a position of control in the world of childhood.” They’d lived three-dimensional lives, whereas Boomers had flattened out into “the demography” — each individual merely a node in a coercive network. And they’d inhabited what Trow characterizes as a true context, while Boomers, to whom “everything is marketed … coldly, yet with a veneer of hateful familiarity,” and who’d been bamboozled by the “aesthetic of the hit” (pre-software recommendation engines), “abandoned shells” (genre conventions, Retro enthusiasms), and “ad hoc contexts” (I think he means the living rooms in which family sitcoms are set), were wasting their lives chasing after fake authenticity.

Trow’s analysis is brilliant… but here’s why this website can’t be described as Trovian. Contra those critics who sniff at what looks like Trow’s nostalgia for upper-class privilege, it strikes me that what Trow is really nostalgic for is… High Middlebrow. He laments the fact that “nego,” developed as armor against Low Middlebrow, has also driven him out of the garden of, e.g., The World’s Fair. Influential members of the generations Trow admired — I call them the Hardboileds, the Partisans, and the New Gods — sold us on High Middlebrow. Which leads me to wonder whether all nobrows secretly feel the same way: do they all yearn to wear the fedora of High Middlebrow without irony? This would explain why Nobrow is so easily leveraged and exploited by Middlebrow in the form of Quatsch. It would also explain aspects of the Cocktail Nation fad, Wes Anderson’s movies, and Dave Eggers’ various projects. Not to mention the one context where Trow fit perfectly: The New Yorker.

The corrosive irony of Nobrow no longer held much consolation, for Trow. Parody, he intones at the most disconsolate point in the text, is an art form for “children who have had imposed upon them a meaningless iconography.” Punk and the punk aesthetic, invented by Boomers and their juniors, is like nothing so much as “what an extraordinary prisoner might do in his cell.” As for the cohort coming of age in the Eighties and Nineties (I’ve dubbed us the Recons and Revivalists), Trow is merciless: “All social memory has been completely obliterated.” If the Boomers were misled into believing that “there are contexts to which television will grant an access” (the Fifties, say) he prophesies, the youth of the Nineties and beyond will be misled into believing that “television itself is a context to which television will grant an access”: i.e., via revivals and rebootings of bygone franchises. Baudrillardian, chilling stuff.

By the time Trow wrote “No Context,” in the mid-Seventies (1974-83), he was a staffer at the [nobrow/high-middlebrow] New Yorker. When Tina Brown became editor and briefly pushed the magazine in a celebrity-obsessed [nobrow/low-middlebrow] direction, he quit and went into exile — first from New York, then from the lower 48, finally from America. He was a Nobrow without a context, and he left us with this counsel: Whenever Low Middlebrow smiles, remind yourself that “there is a lie in the smile” — and remain “glum.” Which, for better or worse, is just what he did.

On his or her birthday, HiLobrow irregularly pays tribute to one of our high-, low-, no-, or hilobrow heroes. Also born this date: Jack Kirby, Morris Graves, Donald Evans, Edward Burne-Jones, Bernard Wolfe, C. Wright Mills, Ben Gazzara.

READ MORE about men and women born on the cusp between the Anti-Anti-Utopian (1934-43) and Blank (1944-53) generations.