A Cyborg Manifest(ed)

By:

September 21, 2010

The popular image is of cyborg as supermodel: a streamlined, metallic mannequin, the flexibility of flesh reinforced with the precision of steel and circuitry; a robot of symmetrical form and shimmering mechanism; an ikon of immortality, flickering agelessly through mechanical reproduction.

We are these things, yes. And have been in metaphor, well before any rude augmentation was imagined, or attempted. But this model, super- or otherwise, is not the best image of the cyborg.

Machines had their eponymous Age, but it was not until becoming Information that they came into their own. And ours. First introduced in a 1960 article notable for its profound reversal of entity and environment, cyborg made its linguistic debut and in so doing, proposed radical new destinies to manifest.

Outer space comes immediately in; the cyborg has always had a special connection to its surround. The thought-experiment of the man outside the space capsule, or rather, of capsules inside the man, allowed our becoming-cyborg to venture far from its native environment. For we are deeply tied to circumstance, and carry it with us as we venture away — atop a mountain, under the sea, into space. To go further we need to boldly rescript the self, to replace systems (respiration, pressure, a desire for meaningful action) that are so aligned with our existence on earth as to forge an identifying matrix with it, impossible to separate out one from the other — or at least, us from it.

Impossible, that is, until one encloses the terms of the proposition to become as self-defined as possible, perhaps in the hopes of aligning with other matrices, or other selves. Or simply to extend beyond entanglement, to leap past limitations and be free.

Let’s turn inward, before turning inside-out. It’s not that we’re pure. We’ve always been mutants, our bodies a hodgepodge of cells and information, a nightmare of maintenance and redundancies, an inefficient delicacy in the face of logic, a porous envelope for a magpie’s trash. All this is collected together in the scrapbook we call DNA; a language that, despite having only 4 letters, comes trailing etymologies that precede and range beyond the human.

And yet, it concerns us to conceive mutations of our own design. It’s horrifying to regard even one small step, “an inverse fuel cell, capable of reducing CO2 to its components with removal of the carbon and recirculation of the oxygen, would eliminate the necessity for lung breathing” (Cyborgs and Space, Clynes and Kline), a horror coded ever more literally in massive amounts of CGI on the multiplexes of our collective consciousness, and in news reports and YouTube videos, as we plumb the depths of the uncanny valley with increasingly viable simulations and automata.

[Young Frankenstein, dir. Mel Brooks, 1974]

Our fear is of the virus, the parasite, the insectoid invasion: the Other inside, which is not so much a loss of control as an overabundance of it. We fear that control will switch our means to its ends, erasing our will as it crunches unconsciously through its script. There is no free will in code; at least, not yet. It is fate, writ in logic and numbers, in flashes of light, in tiny cascading connections both made and missed.

We have abstracted from the soft machine to the more subtle energies of its programming, and with that we reach back to language, the oldest extension of all. To say that we write the self is now literally true, as the genome is decoded and the letters identified and rearranged. We rewrite the codes that program systems, adding a interjection of insulin, or a paragraph of Prozac; even swapping out subjects and objects, as we cloud the probability states in-between.

Old news. All this we have been since our very earliest technologies: stone tools. Fire. Stories. We’ve simply put a finer point on it: spear tips shrink to lithium salts; torches become pacemakers. We turn from Shakespeare to CGAT. And all this time the cyborg has been waiting — waiting; waiting through definitions and back-story, waiting through imaginings and movies, waiting for engineers who might collect and manifest a brilliant new Maria out of the accumulated signals and noise.

[Waiting, performance by Faith Wilding, Womanhouse, 1972]

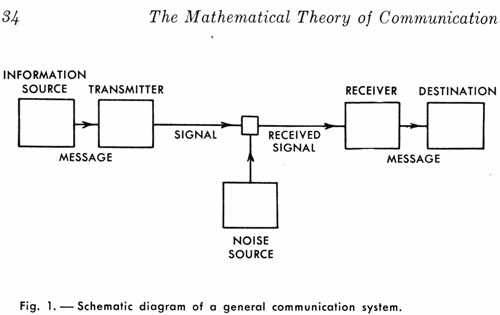

And so we cast our gaze out again, past the moon in which we discern our pale reflection, past the stars outlined by attempts at animals and gods, past futures, past imaginings, past light. But not our bodies; not yet. We needn’t leave our post at ground control; control being, this time, shorthand for C3I: command-control-communication-intelligence. And while control was the first to hand, and intelligence seemed the final frontier, it is communication that finally sparks the cyborg to life.

[Claude Shannon’s communication model, from The Mathematical Theory of Communication]

Within our systems of feedback and aggression and imperative and alteration lies just as deep a desire to connect, to lightly switch roles between sender and receiver and message itself, to dance with others in mutual patterning, to span new segments of the matrix and feel the flows that lay along those lines, to invent our stories and elaborate on those of others. To write ourselves into being — every node is attempted in the telling, and confirmed in the hearing. We live, and we augment, in the flow.

[Pneumatic tubes at the Mayo Clinic]

We have finally arrived. It’s not that each of us may become a cyborg, nor that they walk among us. It’s that we’re all cyborg together, once we but speak. Activated, we find the cyborg to be not, after all, a discrete, polished entity. It is born of us in an ecstasy of communication; it has manifested through our connective technologies; it has launched itself into space, both outer and cyber. It is both embedded in and extended past us all.

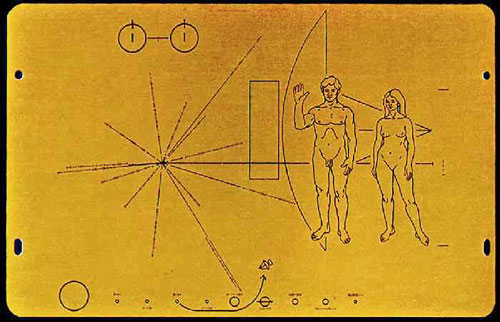

Have we swapped space for time, and infinity for immortality, defying death by covering as much ground as possible before it catches up? It is no accident that the aspect of ourselves that has ventured furthest afield has been our communications, both contained within satellites and broadcast free-range, arcing out past the solar system with anatomical correctness: I Love Lucy, Bach, Jimmy Carter; even the news reports of us landing on the moon. Each message is tethered to us at its origin point, but the tether becomes tenuous as it races outwards, to entropy and beyond.

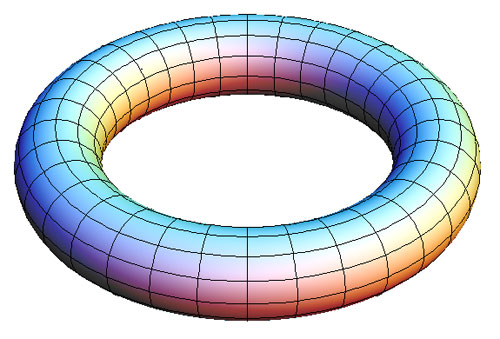

Of course it may be that “beyond” is back home again, depending on space’s own nature. But in every geometry space is reflexive — both outer and inner, personal and cyber — and in all these we are extensible. The paradox of our embedding is that our unbounded imagination is free to make all the giant leaps it can. For different worlds we need only activate the machinery of delight and description, which contains within it its own quickening life.

Does the cyborg wish to be free? Defined within a system, what happens when we attempt to leave that system behind? For the cyborg is, despite and beyond all manifestation, a metaphor. With computers, we have seen the power of metaphor edge back along the beyond to enclose ourselves and our possibilities, to offer limitation in the guise of control. And the idea of immortality, never far, has returned, rephrased, in the idea of the Singularity, the untethered abstraction of the always-already hybrid self, as Matthew Battles has noted previously in this series. Are we to play Moses to the assembled data, unable to cross to the promised land ourselves, but successfully scripting the way?

But freedom may yet be possible. Instead of dreams deferred — to immortality, infinity, information — perhaps we might manifest a better here and now. We are cyborg. We’ve looked in the mirror, and now we must claim the stage; cyborg is less an evolutionary imperative than an aesthetic one. We have the ability to not only convert noise to signal, but to turn both to music. It’s no longer enough to repost links from boingboing and YouTube, to thread oneself into various topics, to buzz about interactivity. The ante is upped.

For we are in society with the cyborg. And as we explore new spaces, as we seek out the company of clever, well-informed entities, who have a good deal of conversation, we may well be reminded that we might seek not only good company — but the best.

[The Assembly at Wanstead House, William Hogarth, painted between 1728-1732]

With this post, HiLobrow continues its participation in 50 Posts about Cyborgs (#50cyborgs on Twitter) a project to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the coining of the term, conceived and hosted by Tim Maly of the blog Quiet Babylon.

READ Matthew Battles on #50cyborgs: Cyborg Theology.

READ MORE about cyborgs on Hilobrow.

READ MORE Peggy Nelson on the Nieman Storyboard on cellphones and the flow.