Cyborg Theology

By:

September 17, 2010

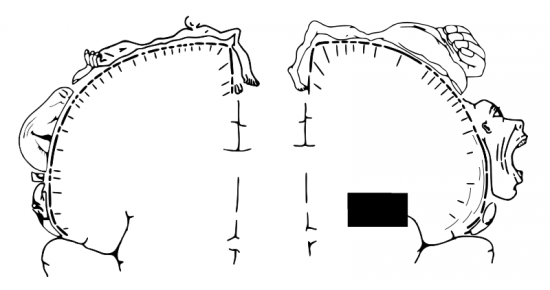

In this disenchanted age, it may seem impertinent to associate cybernetics with religion. In fact, cybernetics is explicitly conceived as a theology. In the 1960 paper “Cyborgs in Space” (in which the word “cyborg” makes its first appearance), Manfred E. Clynes and Nathan S. Kline cast the cybernetic project in religious terms from the very first sentence. “Space travel challenges mankind not only technologically but also spiritually,” they state, “in that it invites man to take an active part in his own biological evolution.” It’s a striking assertion, given that the challenge they take up, while daunting, is quite narrowly specified: the elaboration of systems of cybernetic control that will allow human beings to live and operate in the environment of outer space. But while Clynes & Kline express the problems with which they are concerned — regulation in space of respiration, nutrition, waste management, and the like — in practical and technological terms, it’s clear that in toto some kind of transcendence is evoked by the prospect of the cyborg. In fact they bookend their argument with this numinous note, ending their paper with a statement combining the practical with the spiritual: “Solving the many technological problems involved in manned space flight by adapting man to his environment,” they conclude, “will not only mark a significant step forward in man’s scientific progress, but may well provide a new and larger dimension for man’s spirit as well.”

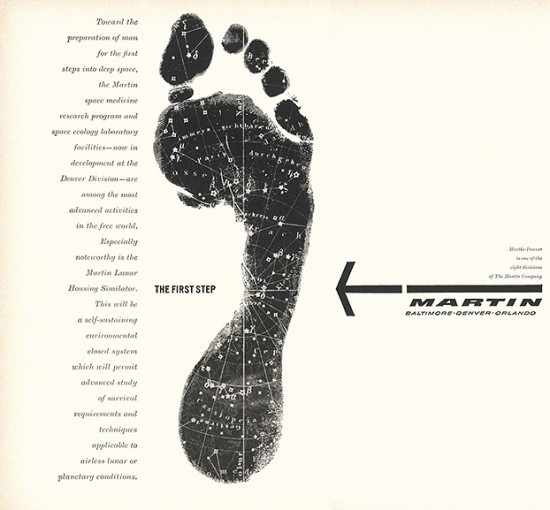

The spiritual strain was very much alive in the budding aerospace industry. As Megan Prelinger shows in her fabulous book Another Science Fiction: Advertising the Space Race 1957–1962, even recruiting ads for companies like Martin and Lockheed combined technological necessity with the numinous. Ten years before Armstrong’s “small step,” and Dave Bowman’s “full-of-stars” cry in 2001: a Space Odyssey, this Martin advertisement (collected with many others by Prelinger) mingled the infant’s footprint with the “star stuff” with which the cyborg seeks (re)union.

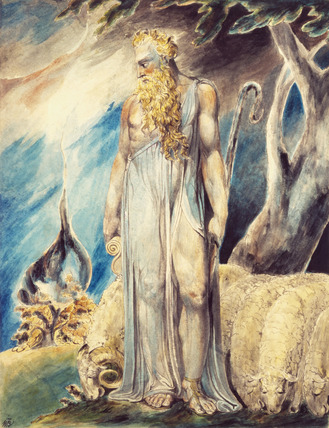

But the spirituality of cyborgs was not spawned by the space race — for transcendence and extension are perennially-sought qualities. The Bible is full of cyborgs. Take Moses, the first great hero (and putative author) of the Torah. In Exodus 3, Moses is tending the flocks of his father-in-law, Jethro, a priest of the Egyptians, when he witnesses the prodigy of the burning bush. The voice claims the mantle of YHWH, the God of Israel, Lord of Moses’ forefathers. As my HiLoBrow colleague Joshua Glenn has already shown, via a heterodox reading of the Torah, rabbinical commentary, and comic books, that there is strong reason to believe that YHWH was a paranoid, hypochondriac extraterrestrial). In the shock and awe of the moment, YHWH commands incredulous Moses to throw his staff to the ground, where it promptly turns into a serpent. Moses recoils, but YHWH commands him to catch it by the tail, whereupon it returns to its original standby state. Later, Moses and his brother Aaron discover that this rod runs a number of useful apps: with it they consume the serpents of Pharoah’s priests (endowed with less powerful cybernetic rods of their own); change the Nile waters to blood; bring forth a plague of frogs from the rivers, canals, and pools of Egypt; make the dust into maggots; bring a storm of rain, hail, and lightning; call locusts out of the east wind; and part the Red Sea.

The staff itself has a curious history; its Biblical description is amplified by legend and midrash. Made by YHWH in the evening of the sixth day of creation, it was of sapphire, and weighed more than four hundred pounds. On it were carved the names of its apps (the characters דצכ עדש באחב, initials of the plagues, which together may be translated as “to the extent of God let these come to pass.”) God gave the rod to Adam as a sort of parting gift when casting him out of Eden. It was handed down from patriarch to patriarch; after Joseph dies it is taken by Jethro, who plants it in his garden. Moses finds it there, recognizes its power, and thus is able to draw it from the ground and claim it as his own. Awed by Moses’ power over the rod, Jethro gives him his daughter in marriage; soon, Moses is turned out in the hills to use the most powerful alien cybernetic tool on the planet to herd his father-in-law’s sheep.

A catalogue of all Biblical cyborgs lies outside the scope of this brief letter. (It’s worth briefly noting that, beyond Torah, Jesus the Christ is God’s cyborg; he’s the feedback mechanism God uses to exert his influence in human affairs. Previous prophets were analog tools, blunt weapons, “instruments of god.” In the world of the Gospels, the Christ is a cybernetic system of the divine, made of meat.)

My purpose here is to note that the cyborg has always been the object and the agent of a necessary theology. At least since the mind-body problem first presented itself, we’re all of us always already cyborgs, hungry little homunculi knit to the levers of the corpse, thrusting ourselves into extension by means of these lurching, crudely-sensing, corporeal cages. Our hands are always already mechanical claws, our sensory palps the wriggling techno-pustules of a blind and curious demiurge driven to remake the set of all things that are the case.

Ultimately, it’s impossible to distinguish cybernetic power from spirit, essence, the sephirot and the élan vital. As Bergson described an animate creature as a thing charged with animating power; as Molière’s quack ascribes opium’s capacity for causing sleep to its “soporific power”; so we connect our gadgets’ connections to their “connectivity.” In our everyday gadget-chat, we’re no more sophisticated than the nineteenth-century spiritualist attributing the floating of tables and the disembodiment of voices to the influence of ectoplasm. No matter how sophisticated one’s sense of the engineering and science involved in one’s cybernetic extensions — the distortion of electric fields by capacitive touch, the modulated flow and impedence of electrons traveling in circuits, the electroluminescent properties of certain semiconductors, the fungibility of pixels — at some level of detail there is a gap where experience and sense data fail us, which only faith can bridge.

Faced with this cybercarnal estrangement, the cyborg theologian proposes a rapture of dissolution, a final disrobing of the homunculi from their quaking and gibbering corpsepods, a merging into a field of quantum entanglement seething with pure unpacketed information. This is the spiritual challenge Clynes & Kline set forth, viewed in its naked form: see now, how even the packets become sad little lost souls, bits ensorcelled by the rumor of identity into assuming addresses, submitting themselves to protocols? For there is a specter haunting the Internet: the specter of Singularity.

But if the notion fills you with horror — if the very syllabling of Singularity sets your meat-mechanical claws waggling, your sense-probes dilating and quaking — perhaps salvation lies not in rejecting cyberspirituality but in embracing it. The animists anciently had their sacred groves, their lively herbs and epiphytes; to them, the river’s every pool and cascade revealed its own sloe-eyed, smiling spirit, ready to aid or to deceive. Every rock was tended by its dutiful gnome, shaggy and wise; every herb had its characteristic mood, its animating green fuse. As with the Sioux warrior — whose piece of perforated feldspar which, hung demurely behind the ear, acted as a cellular conduit of wakan, the spirit-power that hewed and habited the living rock — so one’s cell phone, one’s iPod, one’s GPS receiver, becomes a cheerful-but-fickle agent of its own vital and peculiar energies. In place of the concentrated pandemonium of the Singularity, the cyborg theologian celebrates the distributed spirituality of the Ubiquity; in place of a solar cult of phallically piled-up monocybertheism, she practices a fey and fearsome animism of enchanted gadget-spirits.

This is one of 50 Posts about Cyborgs, a project to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the coining of the term, conceived and hosted by Tim Maly of the blog Quiet Babylon.