Devil’s Dictionary

By:

September 14, 2010

Stephen Hawking took Occam’s Razor to God the other day, something worth noting mainly for the extent of the gap between event and horizon. Nietzsche, or his madman avatar, had famously declared God to be dead back in 1882, and modern science had been holding calling hours for some time prior. But the acknowledgement of science never implies acceptance by all scientists, and somehow it still seems to be news when one of them discards the Ultimate Abstraction as an extraneous entity.

Abstractions are, by their theoretical nature, particularly resistant to being discarded. Platonic Forms may not exist, but once postulated, they are very difficult to un-imagine. A Circle is the ultimate abstraction of all the circular things you, or anyone else, will ever see; similarly for a Pyramid, a Plane, a Point. Now try not to think of a circle. Right. And of course what about Numbers? Do we know them by the robustness of their results, or by the innate power of considering?

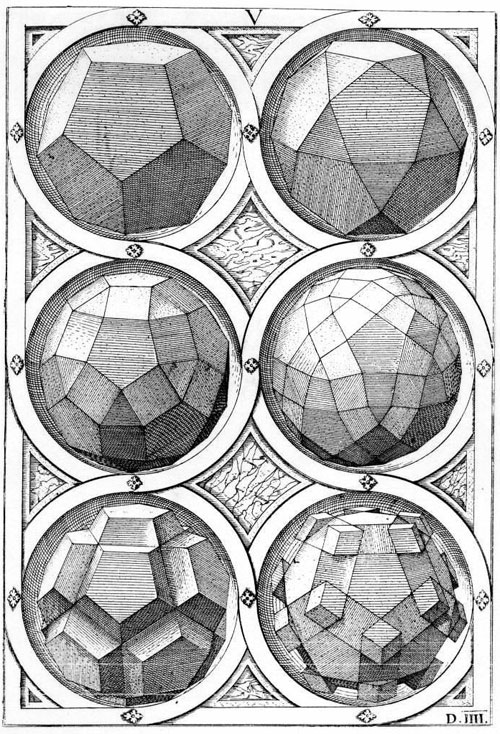

[Dodecahedron and other forms, Wentzel Jamnitzer (1508-1585)]

In any event, the Ultimate Abstraction, when the accessories and incarnations are stripped away, is even more abstract than that. The idea of single and singular God, despite never being quite apart from a host of attendant entities, is a meta-abstraction, the definition of theoretical perfection, the idea of the perfect idea. Reliably difficult to imagine, the Ultimate Abstraction is just as difficult to un-imagine, thus apparently stranding us in a state of continual surprise at its absence.

Devils, however, are specific. They have names. They have needs. They have specialized areas of annoyance. They’re supposed to live under — well, somewhere — but they seem to prowl around here quite a lot. They’re not difficult to un-imagine at all.

Unless we manage to kill them all off.

Cedric, a very specific devil, has died. He died last week, of the fatal facial cancer that is scything through his population, culling them by 70% since 1996. Cedric lived in captivity, where he proved remarkable in his resistance to the cancer, and was hoped to be the saviour of his species, the clues in his body and blood providing immunity for those that had none. But sadly, he too has now succumbed. Like the bats, and the frogs, and even the passenger pigeons before them, the Tasmanian Devils are dying. We may not have shot them out of the sky, but the changes wrought during our reign have altered many areas in catastrophic, and perhaps unfixable, ways. Catastrophic to their current occupants, that is.

And so to us. Of the opposing entities and their absences, I feel the loss of Cedric exceedingly. Our specific world will be a poorer place when our fellow fallen neighbors have gone.