How interesting reading is!

By:

August 20, 2010

The drive from Illinois to Boston is nearly long enough to fit in a Victorian novel — which my family and I did last week, listening to all fifteen disks of Dickens’ Great Expectations while traveling back East on i-90. (It turned out that it wasn’t long enough; we still had two disks to go upon our return.) As the dulcet drawl of BBC Audio’s Martin Jarvis carried us through down the highway, I realized that writing plays a special role in Dickens’ tale. The silver thread of literacy is woven all through the long account of Pip’s travails, testing, proving, and transforming the worth of the characters (written characters, mind you!) and the world in which they move.

For young Pip, literacy is nothing less than the Rubicon running between innocence and experience. From the first lines, letters — these on his parents’ gravestone — exert a lively influence upon his imagination. Pip can’t read yet, but the graven characters speak to him nonetheless:

As I never saw my father or my mother, and never saw any likeness of either of them (for their days were long before the days of photographs), my first fancies regarding what they were like were unreasonably derived from their tombstones. The shape of the letters on my father’s, gave me an odd idea that he was a square, stout, dark man, with curly black hair. From the character and turn of the inscription, “Also Georgiana Wife of the Above,” I drew a childish conclusion that my mother was freckled and sickly. (Chapter 1)

As Pip rows out upon the dark waters of literacy, it makes a change in him perceptible to his wise, unlettered stepfather, Joe:

One night I was sitting in the chimney corner with my slate, expending great efforts on the production of a letter to Joe. I think it must have been a full year after our hunt upon the marshes, for it was a long time after, and it was winter and a hard frost. With an alphabet on the hearth at my feet for reference, I contrived in an hour or two to print and smear this epistle:—

“MI DEER JO i OPE U R KR WITE WELL i OPE i SHAL SON B HABELL 4 2 TEEDGE U JO AN THEN WE SHORL B SO GLODD AN WEN i M PRENGTD 2 U JO WOT LARX AN BLEVE ME INF XN PIP.”

There was no indispensable necessity for my communicating with Joe by letter, inasmuch as he sat beside me and we were alone. But I delivered this written communication (slate and all) with my own hand, and Joe received it as a miracle of erudition.

“I say, Pip, old chap!” cried Joe, opening his blue eyes wide, “what a scholar you are! An’t you?”

“I should like to be,” said I, glancing at the slate as he held it; with a misgiving that the writing was rather hilly.

“Why, here’s a J,” said Joe, “and a O equal to anythink! Here’s a J and a O, Pip, and a J-O, Joe.”

I had never heard Joe read aloud to any greater extent than this monosyllable, and I had observed at church last Sunday, when I accidentally held our Prayer-Book upside down, that it seemed to suit his convenience quite as well as if it had been all right. Wishing to embrace the present occasion of finding out whether in teaching Joe, I should have to begin quite at the beginning, I said, “Ah! But read the rest, Joe.”

“The rest, eh, Pip?” said Joe, looking at it with a slow, searching eye, “One, two, three. Why, here’s three Js, and three Os, and three J-O, Joes in it, Pip!”

I leaned over Joe, and, with the aid of my forefinger read him the whole letter.

“Astonishing!” said Joe, when I had finished. “You ARE a scholar.”

“How do you spell Gargery, Joe?” I asked him, with a modest patronage.

“I don’t spell it at all,” said Joe.

“But supposing you did?”

“It can’t be supposed,” said Joe. “Tho’ I’m uncommon fond of reading, too.”

“Are you, Joe?”

“On-common. Give me,” said Joe, “a good book, or a good newspaper, and sit me down afore a good fire, and I ask no better. Lord!” he continued, after rubbing his knees a little, “when you do come to a J and a O, and says you, “Here, at last, is a J-O, Joe, how interesting reading is!” (Chapter 7)

Pip’s phonetic contrivances, with aitches dropped and replaced in the wrong places, also indicates the vernacular cast of his childhood dialect — a measure of the distance he must row in order to become a gentleman. Joe’s guileless wonder at Pip’s mastery of letters, meanwhile, is charming. In the cruel “modest patronage” with which Pip tests the limits of Joe’s literacy, by contrast, the boy’s later prodigality is prefigured.

Later, Joe produces a sensitive, utopian analysis of the political economics of writing. For although literacy is challenging to acquire, it is not utterly beyond reach. The ladder of letters, for Joe, represents a ready means to class mobility — or more fairly, a token of the equality of humankind. The alphabet, for Joe, is constitution enough.

Joe: “Why, see what a letter you wrote last night! Wrote in print even! I’ve seen letters —Ah! and from gentlefolks!— that I’ll swear weren’t wrote in print,” said Joe.

“I have learnt next to nothing, Joe. You think much of me. It’s only that.”

“Well, Pip,” said Joe, “be it so or be it son’t, you must be a common scholar afore you can be a oncommon one, I should hope! The king upon his throne, with his crown upon his ed, can’t sit and write his acts of Parliament in print, without having begun, when he were a unpromoted Prince, with the alphabet.—Ah!” added Joe, with a shake of the head that was full of meaning, “and begun at A. too, and worked his way to Z. And I know what that is to do, though I can’t say I’ve exactly done it.” (Chapter 9)

As Pip makes his way in the world, other characters produce other writings.

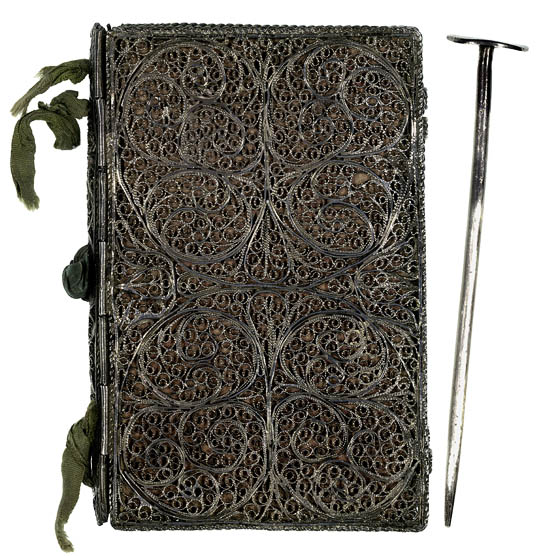

(Miss Havisham) presently rose from her seat, and looked about the blighted room for the means of writing. There were none there, and she took from her pocket a yellow set of ivory tablets, mounted in tarnished gold, and wrote upon them with a pencil in a case of tarnished gold that hung from her neck.

“You are still on friendly terms with Mr. Jaggers?”

“Quite. I dined with him yesterday.”

“This is an authority to him to pay you that money, to lay out at your irresponsible discretion for your friend. I keep no money here; but if you would rather Mr. Jaggers knew nothing of the matter, I will send it to you.”

“Thank you, Miss Havisham; I have not the least objection to receiving it from him.”

She read me what she had written; and it was direct and clear, and evidently intended to absolve me from any suspicion of profiting by the receipt of the money. I took the tablets from her hand, and it trembled again, and it trembled more as she took off the chain to which the pencil was attached, and put it in mine. All this she did without looking at me.

“My name is on the first leaf. If you can ever write under my name, “I forgive her,” though ever so long after my broken heart is dust pray do it!” (Chapter 49)

The tormented Miss Havisham’s ivory writing tablet is an ancient technology. Tablets of wax were used in ancient times for ephemeral note-taking, and small notebooks like Miss Havisham’s — with erasable leaves of ivory, vellum, or washable, plaster-covered paper — were important Renaissance accoutrements. Hamlet cites such a notebook when contemplating his ghostly father’s injunction to “remember me”:

…Remember thee?

Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past,

That youth and observation copied there

And thy commandment all alone shall live

Within the book and volume of my brain. (Hamlet Act 1, Scene 5)

Although such tablets were used into the 19th century, by Dickens’ time they were rare. Miss Havisham’s notebook is a throwback, another reminder of her will to bring time to a stop. Writing her remittance to Pip in such an unusual notebook would enacts her commitment — a signature in their strangeness, the ivory leaves themselves are bond enough. It’s not unlikely Dickens had Hamlet’s “table of memory” in mind when he composed this image. Where Hamlet finds his father’s injunction indelible, Miss Havisham would have Pip’s forgiveness inscribed there.

When in Chapter 53 Pip’s old nemesis, Orlick, traps him in a sluice house on the marshes, planning to kill him, he reveals another side to writing. Like his former master, Pip’s beloved Joe, Orlick is unlettered; but in place of innocence he practices a spite and envy that turn his illiteracy black. He has befriended the forger Compeyson, whose false hyperliteracy he takes for truth. “I’ve took up with new companions, and new masters,” he tells Pip. “Some of ’em writes my letters when I wants ’em wrote,— do you mind?— writes my letters, wolf! They writes fifty hands; they’re not like sneaking you, as writes but one.” It was with such a forged letter that Orlick lured Pip to the marshes.

But when Pip escapes this and other scrapes, and is at last reunited with Joe, he finds that his faithful stepfather has discovered a true and native literacy:

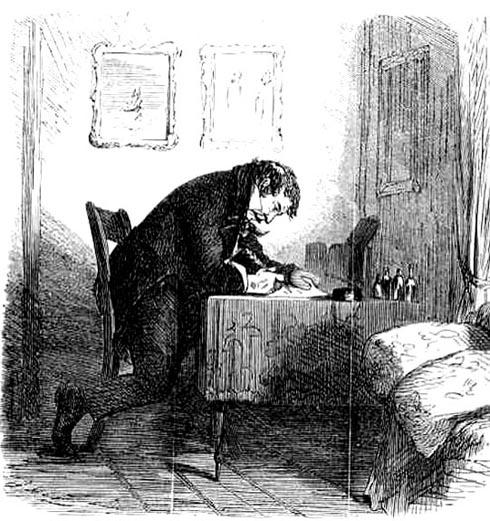

Evidently Biddy had taught Joe to write. As I lay in bed looking at him, it made me, in my weak state, cry again with pleasure to see the pride with which he set about his letter. My bedstead, divested of its curtains, had been removed, with me upon it, into the sitting-room, as the airiest and largest, and the carpet had been taken away, and the room kept always fresh and wholesome night and day. At my own writing-table, pushed into a corner and cumbered with little bottles, Joe now sat down to his great work, first choosing a pen from the pen-tray as if it were a chest of large tools, and tucking up his sleeves as if he were going to wield a crow-bar or sledgehammer. It was necessary for Joe to hold on heavily to the table with his left elbow, and to get his right leg well out behind him, before he could begin; and when he did begin he made every down-stroke so slowly that it might have been six feet long, while at every up-stroke I could hear his pen spluttering extensively. He had a curious idea that the inkstand was on the side of him where it was not, and constantly dipped his pen into space, and seemed quite satisfied with the result. Occasionally, he was tripped up by some orthographical stumbling-block; but on the whole he got on very well indeed; and when he had signed his name, and had removed a finishing blot from the paper to the crown of his head with his two forefingers, he got up and hovered about the table, trying the effect of his performance from various points of view, as it lay there, with unbounded satisfaction. (Chapter 57)

Superficially, Joe’s writing stance sounds clumsy and discomfited. In fact, he writes like an animal — and I mean that in the best possible way, as a human animal doing what comes naturally to itself. Joe approaches the tools of writing as he does those of his smithing trade; with his leg thrown out and his head bowed piously, he takes to his writing hungrily, like a dog following a scent. In Joe, ultimately, Pip discovers his ideal man as an integrated whole: not an alienated gentleman, but a literate savage, spluttering and blotting in honest pursuit of the letters’ native truth.

Pip at gravestone, from David Lean’s 1946 film adaptation, with Anthony Wager as Pip. Writing tables bound in silver filigree, Folger Shakespeare Library, V.a.531. Joe at desk by John McLenan for Harper’s, 1861.