Feedback (4)

By:

August 10, 2010

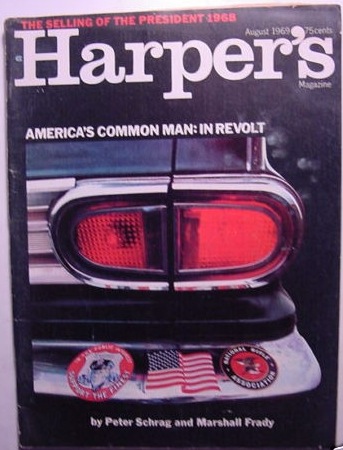

FEED (August 10, 1999): From his autobiography North Toward Home (1967) to his essay collection Terrains of the Heart (1981), and in each of his other dozen books, Willie Morris, who died two Mondays ago, never tired of revisiting his childhood in the Deep South. Though he was a talented, hard-drinking Mississippian writer given to flights of melodrama and bald allegory, Morris was no Faulkner. His florid style — which once led him to recall that a pile of dog shit’s “malodor was, to say the least, obstinate” — was too often combined with the kind of sentimental self-indulgence which inevitably leads one to write a paean to Little League baseball. (Which, in fact, he did.) Let’s remember Morris, then, not for his dubious success as a Southern Writer, but for his brilliant failure as editor-in-chief of Harper’s Magazine.

Having been made, in 1967, the youngest top editor in the history of the country’s oldest literary magazine, the 32-year-old Morris wanted desperately to overcome Harper’s’ well-deserved reputation for being — as he recalled in his second, well-worth-reading autobiography, New York Days (1993) — “remote and docile and safe, wanting in enthusiasm, too lacking in quirks and emotional commitments.” (Call it: middlebrow.) In an effort to “re-make literary America,” he set about stealing New York intellectuals away from Commentary, New Journalism studs from Esquire, and crack reporters from The New York Times. He succeeded, wildly, but only four years into his editorship he ran afoul of the magazine’s publishers, a media conglomerate that wanted less Norman Mailer, and more demographic surveys. His public letter of resignation — “It all boiled down to the money men and the literary men. And, as always, the money men won.” — remains a classic of the “take-this-job-and-shove-it” genre.

Even during the heyday of his years as New York’s hottest New Yorker, Morris wore his own Southernness like a red badge of courage. Norman Podhoretz captured this sense of pride in his analysis of Jimmy Carter: by the ’60s, Podhoretz argued, Southerners had learned to turn their sense of cultural inferiority into one of superiority, by asserting that their tragic sense of life afforded them a profound understanding of the true nature of things. This assessment certainly seems true of Morris, who cast himself as a Good Old Boy, a populist, and a small-town hothead distrustful of big business, the degenerate urban middle class, and self-righteous liberals alike. But although Southernness may have been a source of strength — Harper’s distinguished itself, in the end, as a magazine of intense moral concerns — Morris later felt that his “very Southern pride, and distrust of inherited and entrenched absentee wealth” ultimately rendered him incapable of remaining at the magazine he’d put back on the map.

What can we learn from Morris’ failure? One thing: in the magazine business there is, and will always be, what Morris called “a worm in the lilac.” He wanted to publish a magazine (as he told his colleagues) “willing to fight to the death the pallid formulas and deadening values of the mass media”; but he was employed by a mass media company. That Morris managed to beat the system at all is an astonishing triumph; that he failed is only proof that, in the end, the system can’t be beat. (Alex Kuczynski, writing in yesterday’s New York Times about the ironic juxtaposition of Talk’s launch and Morris’ funeral, notes that the days are long gone when magazines “consistently ignited sweeping public dialogue.”) The only reason Harper’s is still fighting the good fight — publishing morally serious, well-written, and astonishingly long articles, for a general public increasingly unable to focus on anything more complex than the instructions for those new yogurt containers — is because it went non-profit in 1980.

Launched in May 1995, the web magazine FEED — which helped launch the careers of Steven Johnson, Steve Bodow, Keith Gessen, Joshua Micah Marshall, Erik Davis, Christine Kenneally, Alex Abramovich, Chris Lehmann, Sam Lipsyte, Alex Ross, Clay Shirky, Ana Marie Cox, and many others, including yours truly — went offline in the summer of 2001. In June 2010, its archives were made available. This is the fourth in a series reprinting a few of my own favorite FEED Dailies.