Into the Void (4)

By:

July 20, 2010

Watching the last batch of episodes of Lost, it’s been occurring to me just how hard it is to make any kind of story fit together. Whether it’s a novel or a TV series or a set of graphic novels, when you set out to tell a story, most of the time you can hardly glimpse where you’re going to end up. And the best stories are often the most complex, with the most intriguing connections.

The richest seams of storytelling are often the ones you open up by accident, halfway through, and the stuff you’d planned way in advance often fizzles. This is no doubt twice as true if you’re making a television show, and you have actors who want out of their contracts early, or a million other unexpected things happen. But it’s true in every medium: the supplies you cram in your rucksack for the journey ahead often turn out to be useless, and you find great stuff along the way.

What’s the difference between an overcomplicated story with a ton of detours, and a brilliant tapestry? Often, it boils down to whether all your added complications fit within a theme. Here are five rules of thematic storytelling that may help.

1) Storytelling tends towards complexity. Subplots accrue. Cool ideas pop up, and characters at the fringes of your vision tend to crowd into the frame. The more time you have, the more complex your story tends to get, and the more random elements barnacle their way onto your hull.

2) Complexity can add to your story, or it can just be needless. Think of it as the difference between grace notes on the one hand, and red herrings on the other. Not that there’s anything wrong with red herrings. There’s a reason why Five Red Herrings is arguably the best Lord Peter Wimsey novel. (Apologies to Harriet Vane fans.) But often times, red herrings just stink after a bit. Or rather, too many red herrings can feel pointless.

3) The difference between grace notes and red herrings is theme. Not plot. Theme. You can make any amount of complexity figure into your plot — or at least, you can make it appear to, which is near enough. Your MacGuffin can pass through an endless series of hands, or your journey can have endless detours. But incorporating endless complexity into your plot doesn’t save it from being a series of red herrings — only thematic consistency can do that. If your added elements seem to fit a theme, or amplify the central idea of the story, then they’re grace notes.

4) You can’t force things to fit a theme. And you can’t always introduce things for thematic purposes. Theme is harder than plot in many ways. If it’s too self-conscious, it’s deadly and your story turns preachy or bludgeony. We’ve all read books or seen television shows where various characters all spout a particular word or bring up a particular idea, to let you know that’s the theme. (I love the Doctor Who story “Survival,” but it’s not exactly subtle about letting you know its theme.) Often, when you’re writing or otherwise percolating a story, you won’t know what themes come up until you’re a ways into it. With a really good story, you won’t know what themes people are going to see in it until years later in many cases.

5) If you do a good enough job of integrating your complexity into a theme, or a cluster of themes, then the readers/viewers won’t care nearly as much if you don’t explain every last little thing. It’s only when the threads stick out that we can’t stop wondering where they go.

So how do you make sure that your complexity enriches your story instead of burying it? I think that theme is something that sort of bubbles up from the unconscious. It emerges during the telling of the story, and it’s something that must be at least somewhat accidental, or it’s not worthwhile. A story told with a conscious theme in mind is a homily.

At the same time, patterns are bound to become plain as the story emerges. You make choices, your characters make choices, and those choices mean something. Also, your characters talk about what they’re thinking and feeling, and sometimes — we hope — those utterances mean something as well. Those bits of meaning are like sonar pings, and you can sort of triangulate them to arrive at a theme. Except that it’s rarely that tidy, and this is not a science in any way.

You probably don’t want to stop and interrogate your theme when the story is just pouring out of you and the road ahead is clear as daylight. When you’re rolling forward like a juggernaut and everything is flowing, the last thing you want to do is stop and think, “Hey, what does this all add up to?” Do it when you’re stuck, or when you’re editing.

Sometimes you get stuck in a dead end, because all of that joyful downhill racing has left you in a ditch. At such times, you may have to backtrack. You may also want to think about your major characters and what they’re actually thinking, and what they’d really do in this situation. But it’s not a bad idea, also, to sit and think about what you’ve written prior to being stuck, and seeing what it adds up to. And maybe, that helps you see the way forward, or else where you went wrong. Sometimes, it’s clear that it all adds up to something — except for one or two elements that seemed like a great idea at the time.

When your novel is done or your story is otherwise in a first draft sort of state, you can sit and think about theme — and this may help you figure out what to cut, or what you need to develop.

Too much self-conscious theme-wrangling can easily become clumsy or even precious and twee. But I think that to the extent that plot, story, and theme are three different things, the first two depend on the third to achieve real greatness. Anyone can construct a competent plot. Most stories are a variation of “someone achieves a goal, someone learns something, someone takes a journey, blah.” Theme is what elevates plot above gimmick and story above cliché.

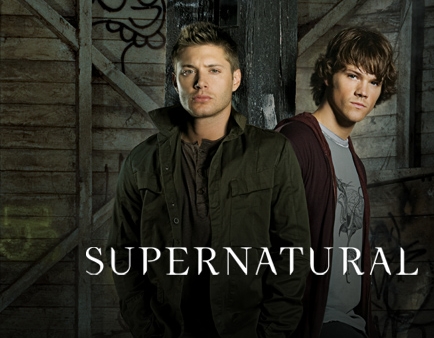

This is why I keep telling anyone who’ll listen that Supernatural is the most literary show on television, possibly ever. Not just because it tells one coherent story from beginning to end, over five seasons. But also because it has a strong thematic texture that’s in the first episode just as much as the last episode. Watch any episode from season one and then the finale, “Swan Song,” and you’ll see the same issues being discussed. The graveyard conversation between Michael and Lucifer could be a Dean-Sam conversation from any episode in the first season: the good son versus the rebellious son.

The reason Sam and Dean beat the Archangel and the Devil is because they’ve outgrown those roles, slowly and painfully, over five seasons. They’ve done what the angels could not — they’ve grown and learned to understand and respect each other. They’ve realized that family is more important than these petty disputes, and that things are always more complex than just “the good son versus the rebellious son.” These roles are the reason why Lucifer and Michael wanted Sam and Dean as vessels in the first place, but the Winchester brothers don’t fit them any more. At the end of the five-year Kripke arc, you no longer need to ask why God would prefer humans to angels — it’s been made plain. And that’s good storytelling, because it’s thematically rich.

Just remember that whatever you think the theme of your work is, your readers/viewers/stalkers will no doubt tell you that it’s something totally different. That doesn’t mean you failed. It probably means you succeeded in creating something coherent and luminescent, after all.

Because we dig the sci-fi blog io9, HILOBROW’s editors have curated a collection of critiques by one of our favorite io9ers: Charlie Jane Anders. This is the fourth in a series of ten. This post was first published on May 20, 2010.