The Anxiety of Connection

By:

July 16, 2010

A new web toy keeps popping up in the writerly streams I follow on Twitter. I Write Like calls itself a “statistical analysis tool, which analyzes your word choice and writing style and compares them with those of the famous writers.” This sort of analytic procedure, once controversial, is now widely accepted; more sophisticated versions have been used to challenge forgeries and authenticate manuscripts that have eluded the critical acument of traditional researchers.

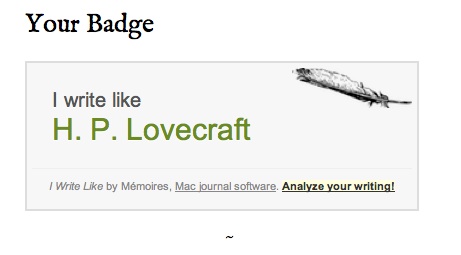

I Write Like’s interface is a simple text box. Enter a few lines or paragraphs of text (no tweets!), click a button marked “Analyze,” and you get a screen like this:

Lots of people have been checking to see how their own writing maps onto the pantheon of possible precursors. Which is exactly what we’re supposed to do; I Write Like makes it easy, with embed codes; links to Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, and Buzz; and opportunities to sign up for newsletters that will help you improve your writing.

Curious, I took a chunk of my own writing and threw it in the box. Here’s the last paragraph of “The Gnomon,” a story I published on HiLobrow back in April:

The people streaming down the escalators joined queues that bent themselves into arcs, forming a great churning spiral of humanity spinning slowly on its axis at the center of the hall. The exhibits themselves had been trampled; coils of crepe and drifts of royal blue fabric caught on the wreckage of shelving and folding chair, of splined plastic and shattered veneer. The spiraling crowd shambled on through the ruins, dragging it with their feet, mixing it into so much particolored flotsam. And in their midst The Gnomon glowered: still erect upon its pedestal, a throbbing core of darkness dragging all towards it. In the spiral’s innermost circle, hands reached out to touch the Gnomon, a wickerwork of arms turning slowly like the spokes of some inexorable wheel. Outward from the Gnomon jetted pullulating ribbons of black as if driven by some nameless wind; they whipped over the heads of the pilgrims, who raised their arms in supplication. The urge to follow was unbearable; I shut my eyes against it, knelt down and touched my forehead to the cool glass beside the escalator. And amid the terrible tolling and the rank odor of compulsion, the lights of the hall began to shut down, one by one; and the fascinating darkness grew until it held illimitable dominion over all.

I would have placed my money on Poe — there’s a direct theft from “The Masque of the Red Death” in the graf, and throughout I was striving to match or adapt the rhythms of the lugubrious bard. To the analyzer, however, I sound like none other than Dan Brown (the analyzer, it should be noted, does not take sales figures into account). But then I tried a few more paragraphs from the story, and they returned varied results: Charles Dickens, Stephen King, James Joyce. This prompted me to grab another paragraph for analysis:

I walked away slowly along the sunny side of the street, reading all the theatrical advertisements in the shop-windows as I went. I found it strange that neither I nor the day seemed in a mourning mood and I felt even annoyed at discovering in myself a sensation of freedom as if I had been freed from something by his death. I wondered at this for, as my uncle had said the night before, he had taught me a great deal. He had studied in the Irish college in Rome and he had taught me to pronounce Latin properly. He had told me stories about the catacombs and about Napoleon Bonaparte, and he had explained to me the meaning of the different ceremonies of the Mass and of the different vestments worn by the priest. Sometimes he had amused himself by putting difficult questions to me, asking me what one should do in certain circumstances or whether such and such sins were mortal or venial or only imperfections. His questions showed me how complex and mysterious were certain institutions of the Church which I had always regarded as the simplest acts. The duties of the priest towards the Eucharist and towards the secrecy of the confessional seemed so grave to me that I wondered how anybody had ever found in himself the courage to undertake them; and I was not surprised when he told me that the fathers of the Church had written books as thick as the Post Office Directory and as closely printed as the law notices in the newspaper, elucidating all these intricate questions. Often when I thought of this I could make no answer or only a very foolish and halting one upon which he used to smile and nod his head twice or thrice. Sometimes he used to put me through the responses of the Mass which he had made me learn by heart; and, as I pattered, he used to smile pensively and nod his head, now and then pushing huge pinches of snuff up each nostril alternately. When he smiled he used to uncover his big discoloured teeth and let his tongue lie upon his lower lip — a habit which had made me feel uneasy in the beginning of our acquaintance before I knew him well.

I Write Like tells me it’s like the work of Charles Dickens. Actually, it’s James Joyce. But that’s not fair, really; the paragraph is from Dubliners, which, while hardly Dickensian, seems written to defy rather than gratify statistical analysis. It’s a striking contrast from the opening paragraphs of Finnegans Wake:

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

Sir Tristram, violer d’amores, fr’over the short sea, had passencore rearrived from North Armorica on this side the scraggy isthmus of Europe Minor to wielderfight his penisolate war: nor had topsawyer’s rocks by the stream Oconee exaggerated themselse to Laurens County’s gorgios while they went doublin their mumper all the time: nor avoice from afire bellowsed mishe mishe to tauftauf thuartpeatrick: not yet, though venissoon after, had a kidscad buttended a bland old isaac: not yet, though all’s fair in vanessy, were sosie sesthers wroth with twone nathandjoe. Rot a peck of pa’s malt had Jhem or Shen brewed by arclight and rory end to the regginbrow was to be seen ringsome on the aquaface.

— for which I Write Like yields an accurate result.

Melville’s The Confidence Man:

At sunrise on a first of April, there appeared, suddenly as Manco Capac at the lake Titicaca, a man in cream-colors, at the water-side in the city of St. Louis.

His cheek was fair, his chin downy, his hair flaxen, his hat a white fur one, with a long fleecy nap. He had neither trunk, valise, carpet-bag, nor parcel. No porter followed him. He was unaccompanied by friends. From the shrugged shoulders, titters, whispers, wonderings of the crowd, it was plain that he was, in the extremest sense of the word, a stranger.

In the same moment with his advent, he stepped aboard the favorite steamer Fidèle, on the point of starting for New Orleans. Stared at, but unsaluted, with the air of one neither courting nor shunning regard, but evenly pursuing the path of duty, lead it through solitudes or cities, he held on his way along [2] the lower deck until he chanced to come to a placard nigh the captain’s office, offering a reward for the capture of a mysterious impostor, supposed to have recently arrived from the East; quite an original genius in his vocation, as would appear, though wherein his originality consisted was not clearly given; but what purported to be a careful description of his person followed.

— to I Write Like’s Borgesian criteria, it’s James Joyce again! But a later passage in the book:

Stools, settees, sofas, divans, ottomans; occupying them are clusters of men, old and young, wise and simple; in their hands are cards spotted with diamonds, spades, clubs, hearts; the favorite games are whist, cribbage, and brag. Lounging in arm-chairs or sauntering among the marble-topped tables, amused with the scene, are the comparatively few, who, instead of having hands in the games, for the most part keep their hands in their pockets. These may be the philosophes. But here and there, with a curious expression, one is reading a small sort of handbill of anonymous poetry, rather wordily entitled:—

“ODE

ON THE INTIMATIONS

OF

DISTRUST IN MAN,

UNWILLINGLY INFERRED FROM REPEATED REPULSES,

IN DISINTERESTED ENDEAVORS

TO PROCURE HIS

CONFIDENCE.”On the floor are many copies, looking as if fluttered down from a balloon. The way they came there was this: A somewhat elderly person, in the quaker dress, [79] had quietly passed through the cabin, and, much in the manner of those railway book-peddlers who precede their proffers of sale by a distribution of puffs, direct or indirect, of the volumes to follow, had, without speaking, handed about the odes, which, for the most part, after a cursory glance, had been disrespectfully tossed aside, as no doubt, the moonstruck production of some wandering rhapsodist.

—I Write Like finds to be like the writing of Mary Shelley. Seems more Joycean to me, but I’m not an algorithm.

I don’t think it’s a problem that I Write Like yields varying results for different passages from the same writer, even when they’re taken from the same work. We’re all things of shreds and patches, after all — shreds within patches within shreds stretching back to the first singers. But where does the impetus for I Write Like come from — what needs does it satisfy? Maybe it’s nothing less than an instance of “Apophrades” — Harold Bloom’s term for the sixth and final (and, we must presume, decadent) of the “revisionary ratios” that comprise his theory, the anxiety of influence. Aprophades is “the return of the dead,” when the work “is now held open to the precursor, where once it was open, and the uncanny effect is that the new poem’s achievement makes it seem to us, not as though the precursor were writing it, but as though the later poet himself had written the precursor’s characteristic work.”

I’m not sure that Bloom’s anxious paradigm holds up for writing on the web, however. “Chance favors the connected mind,” someone said at TED earlier this week; I couldn’t tell from the tweet whether it was Chris Anderson or Steven B. Johnson. We’re eager to see each other in ourselves. We always have been; now we have the tools not only to instantiate those connections, but to fantasize them. With I Write Like, we’re not overcoming Great Writers — we’re friending them.