Planckvision

By:

July 12, 2010

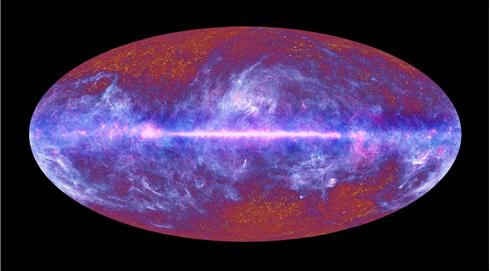

To much fanfare, the European Space Agency last week released this image, hailed as a new map of the universe. It’s what you see if you maintain a stationary position in space 1.5 MILLION km from Earth, blink once every ten months, and see in microwave. (And if that is how you perceive the night sky, I’ll be fleeing now.) The image was gathered over the past year by the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite, which launched last May on an Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana. (Did you know they launched space missions from French Guiana? We don’t need no stinking space shuttles!) Named for the father of quantum physics, the Planck spacecraft is parked at what’s called the Earth/Sol L2 Lagrangian point, an orbit in which it remains stationary relative to our planet and the Sun.

It’s been observed elsewhere that from Planck’s vantage point, the universe looks more than a little bit like the Eye of Sauron. But that’s a trick of your limited perception and geeky hangups, Earthling! In fact, much of what makes this image especially breathtaking to the casual observer — the brightest pixels, in particular the thick horizontal line and wispy blue clouds, which represent our own Milky Way galaxy — will be digitally stripped away by astronomers seeking to measure the cosmic microwave background or CMB, which appears here as faint yellow dots. The CMB is residue from the beginning of the universe, produced less than half a million years after the Big Bang itself. But in its uncanny ocularity, this widely-reported image has captured the imaginations of many not for its esoteric haul of astrophysical data, but on purely aesthetic grounds.

For all its cosmos-revealing power, the Planck map is still an embodied image — by which I mean it’s taken from a particular vantage point. Much can be seen from this perspective; check out the Chromoscope web site, which uses Planck data to produce images of the universe from across the electromagnetic spectrum, revealing whole layers of reality that are otherwise invisible (not to mention instantly fatal) to us. In a way, the Planck, like the mostly-unseen constellations of probes throughout the solar system, is like a very expensive pair of 3D glasses (way beyond the reach of the recycling bin).

Despite being touted as a “map of the universe,” the Planck image reveals how limited our point of view really is — how thoroughly bound up in the vagaries of this particular time and place (cosmically speaking). In a funny way, it makes a putative godlike view of the universe seem more uncanny and impossible than ever — a Net of Indra beyond the ken of any probe or computer analysis.

Of course, the local night sky as it appears to the human eye is more beautiful — but you have to travel to the South Pole or the dark side of the Moon to see it in its full visual-spectrum glory. Part of the power of the Planck map resides in our having lost the night sky’s enchantments to artificial light. In a few short generations, the same technological wave has given us artificial light, taken away the constellations, and extended our senses throughout the electromagnetic spectrum to the ends of space and time. I can’t begin to balance that equation.