Camp, Kitsch & Cheese

By:

June 5, 2010

This article was first published in Hermenaut #11/12 (Winter 1997). Hermenaut was published and edited from 1991-2000 by HiLobrow cofounder Joshua Glenn. Click here to read more from Hermenaut and Hermenaut.com.

[Camp is] terribly hard to define. You have to meditate on it and feel it intuitively, like Laotse’s Tao… Once you’ve done that, you’ll find yourself wanting to use the word whenever you discuss aesthetics or philosophy or almost anything. — Charles Kennedy, in Christopher Isherwood’s novel The World in the Evening (1952)

A sensibility (as distinct from an idea) is one of the hardest things to talk about; but there are special reasons why Camp, in particular, has never been discussed… To talk about Camp [is] to betray it. — Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp” (1964)

Why was camp, a term that academic and MSM cultural critics currently toss around whenever discussing phenomena — “cult” movies, “ugly” clothes, “bad” art or music — whose popularity among hipsters is inexplicable, once considered so difficult to define? The quotes above suggest that it was because intuitive sensibilities cannot be objectively demarcated; or else it was because camp was seen as inextricable from its origins in a set of concealed/flaunted postures [supposedly the term comes from the French slang camper, “to pose in an exaggerated fashion”], gestures, and speech acts of an oppressed late-Victorian queer culture. I’m going to suggest another reason — and, somewhat reluctantly, I’ll define camp.

Queer Studies scholars have every right to resent the manner in which camp has been redefined as an apolitical, aestheticized, and frivolous sensibility stripped from its original context — i.e., as a concrete means for a particular group to critique dominant modes of normality (and as a means to produce “social visibility” for themselves). But even if we could reduce camp to its queer subcultural origins, we’d require a definition of the aesthetic sensibility which goes by the name “camp.” We can’t look to Sontag’s “Notes on Camp,” for this — because she didn’t get it right.

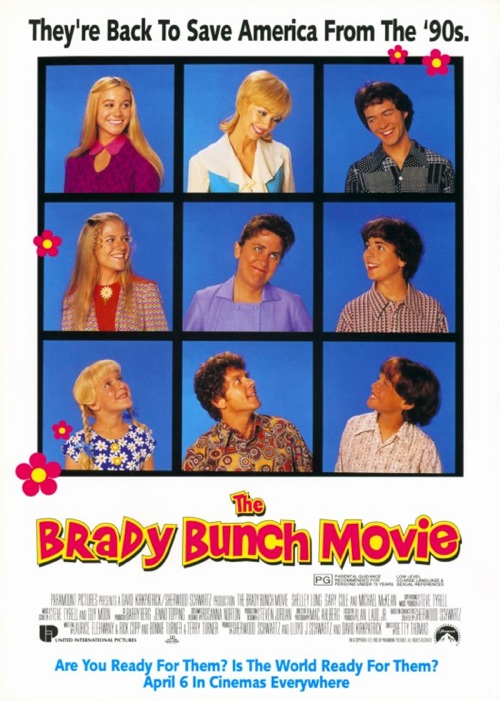

Camp and cheese are reactions to kitsch — i.e., to cultural products intended to be high quality, but highly flawed in conception or taste. People who enjoy kitsch in a naive way may lack good taste, but at least they haven’t lost the capacity to feel. Spare your pity for those hipsters who merely pretend to enjoy kitsch as part of some anti-hip put-on. A couple of years ago, when The Brady Bunch Movie and Pulp Fiction were vying for viewers among the same demographic, I clipped a bunch of articles from alt-newsweeklies around the country in which this anti-hip hipsterism trend was reported on and analyzed. Time and time again, the alt-weeklies confused camp, whose starting place is a mature philosophical irony that’s detached but not disaffected, with cheese: a disaffected, sarcastic defense mechanism as venerable as adolescence itself.

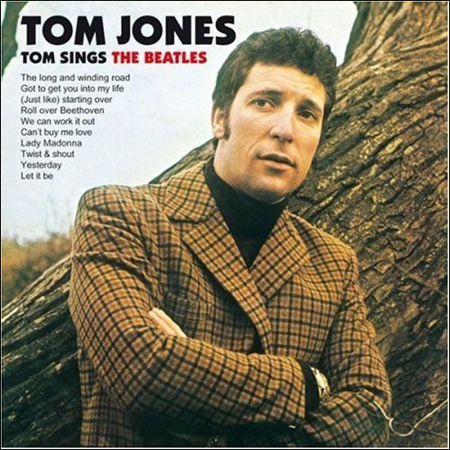

In “Spreading Hip” (LA Weekly), for instance, Arion Berger makes reference to Sontag’s notes on camp in order to bolster his argument that “Hipness used to mean irony, which implied self-awareness; it still means irony, but now demands unwittingness. So it is, for example, in music, the knowing icons of hip (Frank Sinatra) gave way to the semiknowing (Tom Jones), who moved aside for the utterly baffled (Tony Bennett).” First of all, Sinatra and Bennett are vocalists of a different era and order than Jones; it’s an apples and oranges thing. But Berger’s real blunder is to confuse hipness with the camp sensibility. If (for the sake of argument) we agree that Tom Jones is kitsch, then hipsters who pretend to dig Jones aren’t displaying a camp sensibility; they’re being cheesy. People who enjoy Jones should be envied — not mocked — by sarcasm-damaged hipsters.

What about people who feel an emotional connection with the music of Tom Jones while simultaneously recognizing that it’s not “good”? Theirs is an engaged irony which, as camp theorist Esther Newton puts it, “allows one a strong feeling of involvement with a situation or object while simultaneously providing one with a comic appreciation of its contradictions.” Sontag gets this aspect of camp right, when she notes: “Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as ‘a camp,’ they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.” Nobrow hipsters, for whom the highest mode of humor is the “put-on,” are emotionally guarded, terrified of being hurt or ridiculed. Inside their hardboiled shell, they’re a gooey mass of earnest sentimentality. But camp is a negative-dialectical synthesis of sentiment and dispassion. Which, as Isherwood points out, is more or less the Taoist ideal.

Need more clarification? To his fans Liberace was the epitome of cultured taste, but of course we know he was kitsch. However, unlike the not-quite-weird-enough musical stylings of ABBA, say, or the Village People, Liberace-style kitsch is so weird, so outré, that hipsters find it impossible to appropriate as cheese. Liberace didn’t make his work inappropriable on purpose; others, however, have. The director John Waters, for example, described his (excellent) early films, which lovingly celebrate kitsch in an extreme, even terrifying way, as “trash.” He did so in order to prevent hipsters from fake-appreciating his work — as they’ve done with, e.g., the films of Ed Wood. Deploying the term “trash” was a brilliant anti-ironic maneuver on the part of a master ironist.

Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a “lamp”; not a woman, but a “woman”… . — Sontag, “Notes on Camp”

Sontag was a highbrow who wanted to reform Highbrow; in this essay, she adopted a nobrow device — air quotes — to make her point about the camp sensibility. Doing so was a tactical error: cheese is nobrow; camp is hilobrow. To employ Buddhist four-fold logic, which neither rejects nor accepts Western philosophy’s law of contradiction, we might correct Sontag by saying that camp sees a lamp not as a lamp, but a “lamp” — and also as a lamp. Camp recognizes that, e.g., mass-produced Ireland ashtrays and Sacred Heart statues are laughable, a degraded form of nationalistic or religious sentiment. Yet camp is respectful of sentiment, no matter how degraded.

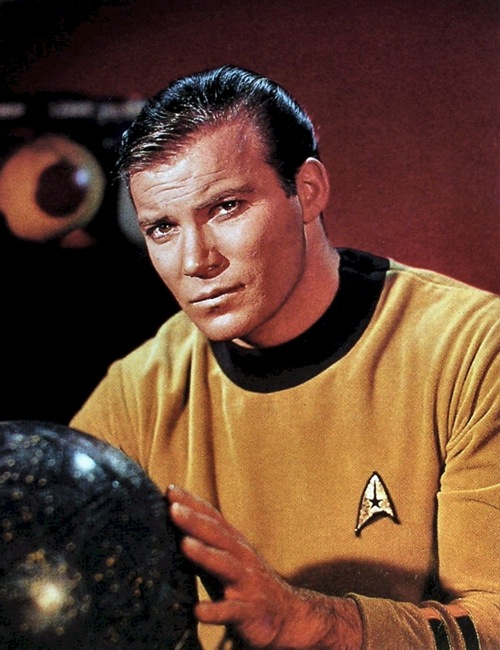

Here in the 1990s, even our most Menckenesque cultural critics appear to be incapable of doing the same. In his article “Anti-Hip” (Boston Phoenix), Geoff Edgers claims that in order to be truly hip, today’s young turk must be anti-hip — which is true enough. But then he goes on to describe how the anti-hip hipster must “pretend to like things that are campy (surf music), horrible (William Shatner’s turn at ‘Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds’), nostalgic (Molly Ringwald), square (Karen Carpenter), or ugly (polyester).” We applaud Edgers for criticizing the anti-hip hipness of his readers; but let’s get it right: Shatner is campy (in a good way), Karen Carpenter is horrible (grotesque, to be precise), surf music is nostalgic, polyester is square, and Molly Ringwald is ugly.

Over in the mainstream media, Jeff Gordinier’s “Camping Out” (Entertainment Weekly) uses the examples of Quentin Tarantino, Nick at Nite, Spike Jonze videos, and the other usual suspects (Tom Jones, The Brady Bunch Movie) to claim that, “In the last year or two, the two halves of the entertainment universe have collided, and what’s left in the debris is neither cool nor uncool but a mutant offspring of both: kitsch… All of a sudden kitsch defines cool.” If Gordinier means that pretending to dig kitsch is hip, then he’s right; that’s been true for decades. However, he’s missing the big picture: what’s changed in recent years is that mass culture now parodies itself for profit, churning out ersatz kitsch (cf. OK soda, Nick at Nite’s faux retro commercials, The Brady Bunch Movie) with the emotional distance pre-packaged. Call it the Mystery Science Theater syndrome.

Alas, too many of my contemporaries either embrace cheese, or become deadly earnest. Which demonstrates, to me, that the two sensibilities are closely related. Is it too soon to predict that, in the year 2000, a talented nobrow artist will discover a means of dialectically synthesizing cheese and earnestness — and thereby become a media darling, beloved by hipsters and middlebrows?*

In a 1992 New York Times trend piece (“First There Was Camp; Now There’s Cheese”), Michiko Kakutani blamed the Revivalist generation’s stunted emotional life on their upbringing. This is a generation, writes the OGXer, that “grew up suspicious of sincerity; wary of making emotional, political, or artistic commitments; and whose cynical, defensive mantra is, ‘Hey, I’m cool, you’re cool, and we won’t endanger our coolness by ever admitting to a genuine emotion or serious ambition.'” Cheese started out “being sort of mean-spirited, hostile like the hippies were to Middle America. It was a way of mocking the lame sort of conservative, blatantly superficial products of American mass-media culture,” a student at Boston’s Berklee School of Music told Kakutani. “The problem is, people started to take Cheese seriously. They’re not saying anymore it’s so bad, it’s a joke…”

Kakutani’s interviewee isn’t wrong to criticize the popularity, among his peers, of mass culture products featuring what I’ve called pre-packaged emotional distance. He’s right that something has changed. The mildly subversive parodic possibilities that, e.g., the Situationists, the editors of Mad, and the early Saturday Night Live once found in mass culture products have today been all but neutralized. Dan Aykroyd’s cheesy fake TV commercials were edgy-ish; today, the edge is off. Too bad that instead of rejecting cheese in favor of camp, sensitive and intelligent young men and women hanker for the days of edgy cheese.

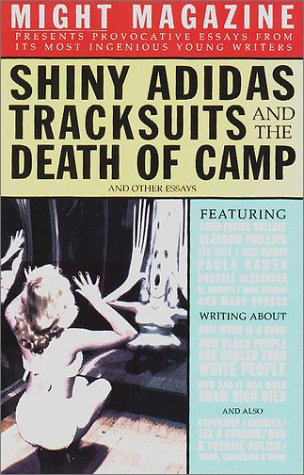

Writing in Might magazine (“Shiny Adidas Track-suits and the Death of Camp”), young novelist Glasgow Phillips berates “those of you who claim to enjoy [Spelling television shows like 90210] genuinely, that you really, really like them…” he writes. “Burying your head in the sand of Camp sensibility is a logical move for a cultural ostrich, but don’t imagine that it’s anything else.” By “camp,” of course, he means “edgeless cheese.” Phillips’ inability to recognize any possible response to 90210 and Melrose Place other than edgy cheese marks him as a nobrow. (Hilobrows enjoy 90210 and Melrose Place.) David Eggers and his fellow Might editors have followed suit, publishing a book titled For the Love of Cheese; it urges readers to “discover your inner cheesiness and rejoice.”

Samuel Beckett’s novel Watt makes a similar point. Commenting on three types of laughter, Erskine notes:

The bitter laugh laughs at that which is not good, it is the ethical laugh. The hollow laugh laughs at that which is not true, it is the intellectual laugh. Not good! Not true! Well well. But the mirthless laugh is the dianoetic laugh, down the snout — Haw! — so. It is the laugh of laughs, the risus purus, the laugh laughing at the laugh, the beholding, the saluting of the highest joke, in a word the laugh that laughs — silence please — at that which is unhappy.

Right! The ethical anti-highbrow laughs bitterly at High Middlebrow, which is irreligious yet pious; meanwhile, the intellectual anti-lowbrow laughs hollowly at Low Middlebrow, whose cobbled-together spirituality is bogus. Whence the mirthless laugh? It’s an expression of Nobrow’s edgy cheese sensibility. Haw!

Like many other hilobrows, from Jarry to Adorno to Godard, Beckett enacts the hilobrow mode of laughter — which doesn’t laugh at what’s unhappy; and which doesn’t posit a fallen world, a degraded culture as the highest joke — while steadfastly refusing to define it. (Erskine doesn’t mention hilobrow laughter as a possibility!) This, finally is the most important reason why camp is so difficult to define and discuss. Some of its most articulate, insightful acolytes insist that to do so is taboo.

They’re right to fear idolatry. Camp hasn’t been well served by its best-known spokespersons. Sontag, for example, claims in “Notes” that the “whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious. More precisely, Camp involves a new, more complex relation to ‘the serious.’ One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.” Huh? The second half of her statement, beginning with “more precisely,” accurately describes engaged irony, or camp; as Isherwood has Charles Kennedy put it, “You can’t camp about something you don’t take seriously. You’re not making fun of it; you’re making fun out of it.” However, the first half of Sontag’s describes not camp, but cheese — whether of the edgy or edgeless variety.

Confusion between camp and cheese has plagued us ever since. Which is why I’m foolishly rushing in where hilobrows like Beckett fear to tread. Here in the 1990s, this confusion has become a crisis.

For example: in “The Dark Side of Camp” (The Washington Monthly), Gareth Cook writes that, these days, “camp’s irony and detachment are everywhere, almost to the point where they threaten to squeeze somber, reflective thoughts out of the national conversation… [Camp is] a way of avoiding choices and responsibility.” No: cheese’s detachment is everywhere; cheese is a way of avoiding choices and responsibility. If a thoughtful writer like Cook is confused, just imagine how muddled others are.

Take Neal Karlen, whose essay “Terminal Kitsch” appeared recently on the back page of The New York Times Magazine. Noting that he shared with his fiancée “a long-standing love of the campy [read: cheesy] esthetic that recycles the lowest of pop culture — The Brady Bunch, Pop-Tarts, and Wayne Newton — into hipster icons,” Karlen recounts how the two of them traveled to Las Vegas to “celebrate our marriage amid the tackiness.” While wallowing in the cheese sensibility, Karlen had a Glasgow Phillips-like epiphany. Wayne Newton graciously welcomed the newly-weds, and they felt ashamed; a few months later, their hipster marriage broke up. “Hip is not necessarily from the heart,” Karlen’s essay concludes. “One should not mock Las Vegas singers who are nice enough to send Champagne upstairs to honor the marriage of the mockers. And… irony [read: sarcasm] is a terrible companion on Valentine’s Day.”

Karlen’s conclusion, like his essay, is lame. The editors of Motorbooty put it much better, when they recently claimed that “Irony is not making fun of Elvis, it’s making fun of people who make fun of Elvis.” So next time you’re about to reflexively scoff at kitsch — whether it’s Margaret Keane’s Big Eye paintings, Mexican wrestlers, truck drivers, ladies with elaborately decorated fingernails, Green Acres, bowling paraphernalia, or elevator music — stop! The love you save may be your own.

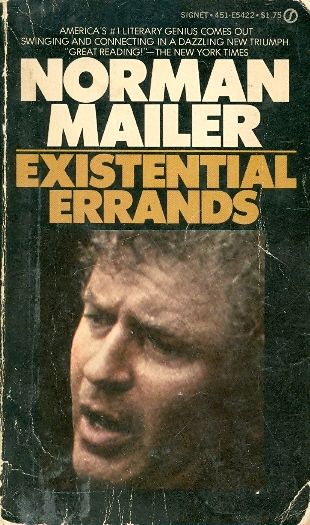

However, taking things seriously is not an antidote to camp. Phillips, Cook, Karlen, and others who’d have us cultivate gravitas might imagine they’re opposed to camp, but (unless they’re earnest, instead of serious) they aren’t. Blame the confusion on Sontag — and also on Norman Mailer, whose introduction to his 1973 collection, Existential Errands, reinforced the notion that the point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Late Sixties-era camp, according to Mailer, had sucked everything out of the intellectual “air” except for “gesture, role, costume, supposition, and borrowed manner.” By writing about boxing and bullfights, Mailer hoped to create an air so “livid” that “Camp [would be] stripped of its marks of quotation, and put-ons shrivel.” No! Cheese uses air quotes and favors the put-on; cheese is earnest, but anti-serious.

The engaged irony of camp is never earnest, but it does not exclude seriousness. In fact, in a culture ruled (as ours is) by the law of non-contradiction, engaged irony might be more aptly classified as a mode of gravitas, not levitas. However, as noted earlier, camp is a negative-dialectical phenomenon. As camp theorist Scott Long puts it, camp “does not merely invert the opposition between the trivial and the serious; it posits a stance, detached, calm, and free, from which the opposition as a whole and its attendant terms can be perceived and judged.” If this sounds more like philosophical irony than camp, it’s true that the former is a way station en route to the latter. If one continues on past that point, however, you come to see the opposition itself as absurd, based — as the same theorist puts it, “on a higher and more encompassing sense of absurdity.” Right. Cheese is a sensibility predicated upon lower forms of absurdity; camp is predicated upon higher ones.

We need to contemplate the difficult notion of engaged detachment, and vigorously oppose apathetic disaffection masquerading as the same thing. Back in camp’s early days, Oscar Wilde did so. In A Woman of No Importance, Lord Illingworth remarks that “People today are so absolutely superficial that they don’t understand the philosophy of the superficial.” Glasgow Phillips and others who’d have us reject the edgeless cheese sensibility aren’t wrong; but they fail to grasp the philosophy of camp.

* I didn’t write that paragraph in 1997! However, this essay could be read as a prediction about the advent of quatsch, and the juggernaut effect that one figure in particular who’s named herein would shortly have on the culture.

READ MORE essays reprinted from Hermenaut.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE