Daniel Clowes: Q&A (1)

By:

April 9, 2010

This article was first published in Hermenaut #15 (Summer 1999). Hermenaut was published and edited from 1991-2000 by HiLobrow cofounder Joshua Glenn. Click here to read more from Hermenaut and Hermenaut.com.

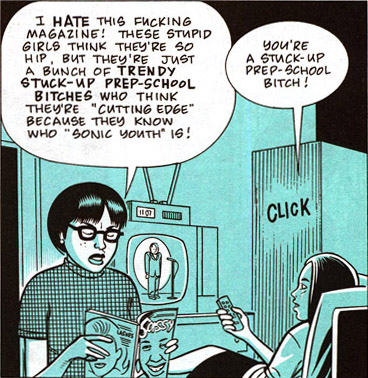

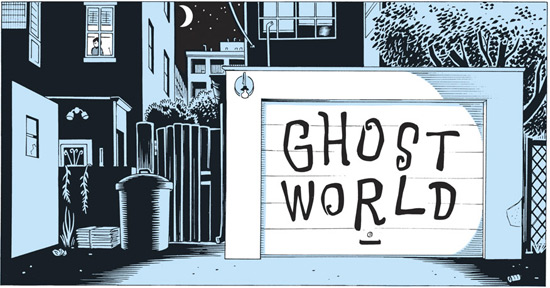

This summer, the University Press of Mississippi will publish Daniel Clowes: Conversations, edited by Ken Parille and Isaac Cates. The collection includes an interview that I did with Clowes for Hermenaut in May 1999, when the movie version of Clowes’ graphic novel Ghost World (1998), whose protagonists are the “post-adolescent chums” Enid Coleslaw and Rebecca Doppelmeyer, was in development. Here’s an excerpt from the interview’s original introduction:

Born in Chicago in 1961, Daniel Clowes toils away in what has become, partly by default, the end-of-the-twentieth-century’s most important narrative medium: the comic book. After publishing six issues of the much-missed comic book Lloyd Llewellyn, and having contributed to Feral House’s ground-breaking book Cad, in 1989 Clowes created the comics magazine Eightball (published, like LLLL, by Fantagraphics). Self-described as an “orgy of spite, vengeance, hopelessness, despair, and sexual perversion,” Eightball has provided innumerable short stories and gags, as well as the graphic novels Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron, Ghost World, and Pussey! to a culture in its death throes; now in its twentieth issue, it has been one of the few consistently good things about the past decade.

To coincide with the publication, this month, of Clowes’ new graphic novel, Wilson (Drawn & Quarterly), I’ve reproduced the 1999 interview in its entirety. I’ve also resurrected a never-before-published interview I did with Clowes in 2002.

HERMENAUT: How’re you doing?

CLOWES: I’m not doing too good, actually. I just found out I lost fifteen pages of original artwork, via UPS. All the good Ghost World stuff was in a show in France: I’ve never sold a single page from Ghost World. What a disaster! I told the guy to insure it for thirty thousand dollars and he insured it for thirty thousand francs instead. Now I’m going to have to sue this poor French guy who doesn’t have any money…

HERMENAUT: Can’t you sue UPS instead?

CLOWES: All I’d like to do is sponsor is one of these disgruntled employees to go in there and kill everybody. I wonder how I can do that? I’ve gotta start a program. You know, I’ve never had a problem with the Post Office, but I’ve had dozens of problems with UPS. I fucking hate that company! [Note: The artwork was recovered shortly after this, but Clowes insisted we leave his anti-UPS sentiments in.] But let’s get started.

HERMENAUT: As we were putting together the forthcoming issue of Hermenaut, which is on “Fake Authenticity,” and which is going to feature articles about the struggle to create yourself instead of just passively existing, and the pleasures and perils of irony, and loving “bad” music and TV shows or just “loving” them, and the lure of “authentic”-seeming lifestyles, it became clear… [beep on line.]

CLOWES: Was that you?

HERMENAUT: No, I don’t know what that was.

CLOWES: I think it was UPS… they must have heard about my program!

HERMENAUT: …it became clear that we had to talk to you, because these are all recurring themes in your comics. In fact, I probably first started being obsessed with fake authenticity several years ago when I read your story “Chicago,” in Eightball, where you describe the Chicago of your adolescence as having been “an entire city made up of those ‘Ye Olde’-type bars and restaurants with intentionally goofy W.C. Fields-inspired names [like] Q.B. Bushwackers, D.B. Wisenheimer, and P.J. Dinglehoffers.” So you’re obviously good at puncturing examples of fake authenticity. I don’t think you’ve shown much sympathy, though, for the person who’s all too aware of fake authenticity, who’s an ironist tortured by his or her own inability to settle into a belief system or a lifestyle… until Ghost World. Enid Coleslaw seems to me to be a real anti-hero of authenticity. Why make her a teenage girl?

CLOWES: It was very safe for me to say anything I wanted through Enid, and through Rebecca, who, by the way, has about twenty percent of the important lines — it was very liberating. Because teenage girls are allowed to struggle to define themselves, and to over-react to everything, in a way that the rest of us aren’t.

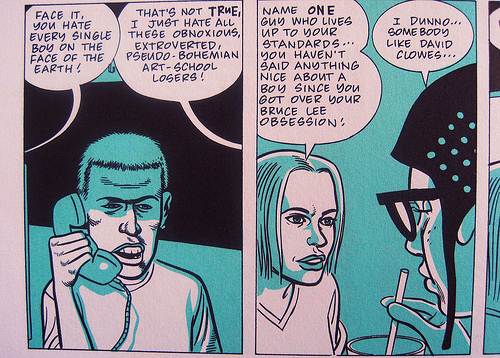

HERMENAUT: You told Dan Raeburn of The Imp that “basically the girls have all my opinions… If I had some cranky old man saying all the same stuff it would just seem awful. He’d be a horrible monster.”

CLOWES: Right. They’re me. And what they go through is something which at that time of my life I was heavily caught up in — not so much “I’m going to wear a hat today!” but more of a “What kind of person am I?” kind of thing. I could never figure out where I fit in, because I wasn’t exactly a nerd — I mean, I was to some degree, but I wasn’t smart enough to be a nerd, I wasn’t, you know, good at math — so I didn’t really fit into that, and even though I didn’t necessarily try new things each day like Enid did, I was searching for something to be a part of, asking “What am I?” I still have never figured that out. There’s endlessly an issue of identity I’m trying to figure out.

HERMENAUT: I want to get back to that, but first I’d like put Ghost World in context of everything else you’ve done. The Philadelphia City Paper says, of Ghost World, that, “read correctly, it almost looks like a repudiation of [your] past work.” They imply you’ve stopped being satirical and have become sincere, serious, even sentimental.

CLOWES: I think that’s really shallow. People like to do that, where they say, “Oh, your old work was just all funny and stupid, and your new work is really strange and deep!” I think there’s a lot of overlap and similarities between the old and the new, they’re just being lazy in their criticism.

HERMENAUT: You are one of those artists who keeps re-working the same themes, over and over again, from different angles.

CLOWES: Right, and they’re not really conscious themes. They’re just the things that keep interesting me. In the beginning it always seems like a Bold New Direction, then half-way through I realize “Oh yeah, that’s sort of similar to that other thing I did!”

HERMENAUT: So Ghost World, despite being about teenage girls, is not a radical break with Velvet Glove, or your new David Boring adventures. But it is more commercial, in a way, right? I have to imagine that one reason Ghost World has been optioned for a movie is because of the perceived huge audience…

CLOWES: I thought that was the most commercial idea I could ever have, two teenage girls. I thought, “They’re going to love to make this!” But once you get to Hollywood, everybody says, “Nobody wants to see another movie about two teenage girls, those movies never make any money. The movies that make money, that get the teenage girl audiences, are the ones that have Leonardo DiCaprio, action and intrigue.” Teenage girls apparently don’t want to see accurate depictions of themselves. So, unfortunately, it’s not as commercial as it sounds. I think if you made the film, and you got a screening audience of teenage girls, they would love it. But you’d have to force them at gunpoint to go into the theater.

HERMENAUT: It’s such a mistake to aim a movie, or anything, at a demographic. Artistic considerations aside, it just seems like you can never hit the target.

CLOWES: I’ve always felt that if you took the audience for Seventeen magazine and ran a demographic on it you’d probably find that there are less readers that are actually seventeen than any other age group. I’m sure ninety percent of them are thirteen, and then there are the dirty old thirty-five-year-old men…

HERMENAUT: When we started publishing Hermenaut, we were all in our twenties and obsessed with Sassy and 90210…

CLOWES: I’m still in that phase, actually! Though I had Enid and Rebecca hate Sassy, because that’s an example of something which is too aware of what it is; it’s trying to sell them something by figuring out what they’re all about. They would like a magazine making a lame attempt to be Sassy, though — a Japanese version, say.

HERMENAUT: Back to the question of identity: In the very first installment of Ghost World, Enid makes fun of Rebecca for only going out with guys “who have some lame fake shtick.” She mentions one ex-boyfriend who always dressed like he was from the ’40s, and another guy who looked like “a gay tennis player from the ’20s” (which is a great line). But then, in the “Punk Day” installment, Enid complains, “I wish I could just come up with one perfect look and stick with it… Like what if I bought some entire matching 1930s wardrobe and wore that every day… The trouble with that is you look really stupid and pretentious if you go to a mall or a Taco Bell or something… And you have to act a certain way and drive an old car and everything and it’s a real pain in the ass!” She’s caught in this contradiction.

CLOWES: But I think it’s a contradiction that any person I would like or respect would probably relate to. I imagine there are a lot of people who couldn’t relate to that kind of character at all, but the kind of people I would want to know are the people who have the same dilemma: “Who am I?”

HERMENAUT: Yet you’ve portrayed this kind of person in other strips — the character Epps, in “Gynecology,” for example. That story, which I think was written at the same time as the Ghost World stories, has a kind of Bela Lugosi-like narration pointing out that Epps’s various shticks — “asexuality,” “morbid vulgarity,” “the Joe Lunchpail common man phase,” the “intentionally unfashionable, world-weary misanthrope” — are mannered and precious. So why do we like Enid, who seems to cycle through shticks even faster than Epps?

CLOWES: I think it’s just the direction I’m coming at the character from. I’m coming at Epps as a horrible version of my worst feelings, and I’m coming at Enid as a sympathetic version of these same feelings. It’s in the way that it’s presented. I liked Enid, I didn’t like Epps, and that comes through.

HERMENAUT: Why, then, has Enid been described, by some of your reviewers, as a hateful person, a bored suburbanite, a freak?

CLOWES: I’ve read reviews that say, “Clowes obviously hates these characters, and is making fun of them…” and of course that’s not true. But Enid is a freak, in a way. There’s no real place for her. That’s why it’s hard to think of a sequel to that story, because where could she go?

HERMENAUT: Obviously not Chicago, not the way you’ve portrayed it, as being full of “Jim Belushi-guys,” these obnoxious fucks with bad haircuts who are so settled into their shtick they don’t even know it’s a shtick. But didn’t you ever wish you could just be one of these stupid, happy people who never agonize about who they are?

CLOWES: No! I always knew that I could only be like that if my awareness were somehow diminished, and I wouldn’t want that. The only way you can define yourself is against types of people, anyway. You sort of negate everybody else, and then… where are you?

HERMENAUT: World Art asked you, in an interview about Ghost World, if at some point the process of defining her self in terms of separation from everything else can ever end for Enid, and you said, “It hasn’t for me, so I don’t know. It’s an ongoing process.”

CLOWES: It hasn’t gotten any better!

HERMENAUT: The end of Ghost World, though, although it’s ambiguous, seems to suggest that Enid may have finally settled — that’s the wrong word — made some kind of leap into a look, an identity that she can live with.

CLOWES: That was sort of the idea, that she was taking that step toward “This is my final look.” I tried to make it a hopeful ending, I thought she was going on to do something interesting, certainly more interesting than Rebecca.

HERMENAUT: In Enid’s final look I think I can recognize a kind of post-shtick shtick I’ve seen before: one shared by people who haven’t settled into an easy hipsterism, but who also haven’t given up on being ironists. I call it the “regular style.” You come as close to looking like a ’40s or ’50s or early ’60s person as you can without actually wearing the vintage clothes.

CLOWES: I guess that’s basically what I’ve settled on after all these years, what I think of as the “Standard, Normal Clothes That A Man Would Wear.” My look these days is based on what my dad would have worn in 1965. It can be surprisingly difficult to pull it off, though. It would be so much easier just to walk around in a Bulls T-shirt.

HERMENAUT: I remember in the ’80s, the Cosby era, trying to find a sweater that didn’t have huge patches of color all over it…

CLOWES: People don’t believe me when I tell them how impossible it was to get non-bellbottom pants in 1977! When I learned about punk, I had to get non-bellbottom pants, but it was literally impossible. I had to have them made, get girls to sew them for me. You can’t imagine how that would be your only choice. You think, “Well, there’s always been straight-leg pants…” but I defy anybody to find them in 1977. Just look through some old catalogs. And today it’s very tough to find anything without a logo on it. I won’t buy anything with a logo.

HERMENAUT: So much for the ironic self; can we talk about irony in general? After we did our “Camp/Kitsch” issue a couple of years ago, you wrote me a postcard that said, “‘Irony’ is a word that usually makes my eyeballs bleed!” People have such a one-dimensional idea of what irony is, don’t they? Some of Ghost World’s reviewers called Enid and Rebecca “supremely ironic teenagers,” who are “trapped in a world of self-referential irony and pop-culture obsession,” and who “avoid the outside world by hiding behind a wall of would-be hipness.”

CLOWES: I see it exactly the opposite way. Reviews say, “These two bored Gen X girls…” and I think these two girls are the least bored people I’ve ever created! They’re never bored, because they make something interesting out of everything.

HERMENAUT: But is “interesting” enough? In the “Ghost World” installment, Rebecca says she loves this terrible stand-up comic, not just because he’s a bad comedian but because his “weirdo” act just doesn’t work. And in the “Hubba, Hubba!” installment they go to this terrible faux-’50s strip-mall diner — “the Mona Lisa of the bad, fake diners.” They make fun of it mercilessly for not getting the ’50s even halfway right, but then Enid asks, “Isn’t this place the greatest ever!?… Could they possibly be more clueless!? I’m so happy we’re here!” So do they really love the comedian and the diner, or do they just “love” them?

CLOWES: What they love is that there’s some sense of humanity in the failure of these things. I think the thing that they’re opposed to is the lack of humanity in these whitewashed images around them. If there were a perfectly-conceived ’50s diner, they wouldn’t find that appealing because it would have this air of some corporate committee that had figured out every angle and made it somehow palatable. But the fact is that the one they’ve picked is obviously created by people who have no idea what they’re doing, and they’re sort of inept at it — that’s what Enid and Rebecca are looking for. They’re not laughing at it, they’re really sort of loving it. They’re able to elevate every experience into something artistic and exciting.

HERMENAUT: There’s a recurring refrain, spoken by Enid: “This comedian is God.” “This diner is God.” Are these moments the author’s way of saying, “They really love these things”? Are these things actually God?

CLOWES: I think so. That’s somewhat literal. There’s some sort of spiritual component there.

HERMENAUT: Does Enid also really love the sex shop? She seems to, particularly in the way she’s seen wearing the bondage mask on the street later, it’s all very funny — but it also sort of seems like she’s just in there to make all the old perverts feel uncomfortable. Is she just being cruel, like she is when she entices the “bearded windbreaker” man to go on a fake blind date?

CLOWES: No. I wanted that strip to seem like she was a kid in a candy store, like this was the greatest moment of her life. She had no idea what it was going to be like, and she can’t believe how great it is. That’s based on an experience I had with my wife. We were in Germany, and we went into all these porn shops, and she was so elated that you could buy these wacky boots, like, “There’s this amazing shoe store where you can buy these great boots!” She was completely oblivious to the giant dildos.

HERMENAUT: Speaking of having a child-like attachment to silly objects, why, in the “Garage Sale” installment, won’t Enid sell her “Goofie Gus” doll — which seems as significant as the “Mister Jones” statuette in Velvet Glove, and the “Dr. Disguise” figures in “Gynecology” — to a guy, just because his haircut is too trendy? [Note: Ten years later, I’d edit a book about people’s weird stuff and its personal meaning.]

CLOWES: I think you should be able to look at somebody’s stuff and it really says something about them, their aesthetic. Often I look at people’s apartments and I think, “Well, you have this stuff because other people have this stuff.” I think, “This stuff just doesn’t quite have it.” I know that the things I have, every single item on display, has personal meaning, some undefinable quality; each item is something that I need to look at every day. That’s how Enid feels about “Goofie Gus.”

HERMENAUT: You show Enid’s shelves groaning with ponderous sex books, ’60s French yé-yé girl records, Scooby-Doo stuff, grotesque dolls. This is a self-portrait, right? In your story “The Party,” you depict yourself as thinking, “Jesus, it always depresses me to see the stuff that hipsters have on display in their apartments… It always seems so childish and unoriginal, but it’s really not much different from my stuff.” Why are you, and Enid, so attached to this, well, kitsch?

CLOWES: I don’t like how the word “kitsch” is usually used. Like I said, I take it more seriously than just: “Amusing Things To Laugh At.” Actually, although I think about stuff from my own childhood a lot, things I haven’t seen in years, all I have to do is see the thing once and I’m cured of it. I’ve recently bought video tapes of cartoons I hadn’t seen since I was four or five years old, and I’m enthralled by them exactly one time, by this feeling of “Wow, this is what I was so interested in?” My memory had turned them into something much more fascinating than they actually were.

HERMENAUT: Like Enid and Rebecca’s trip to “Cavetown, USA,” the stone-age theme park that turns out to be abandoned and depressing?

CLOWES: Exactly.

HERMENAUT: So through irony, Enid creatively finds ways to love things that sincere, earnest people would find unlovable. She seems, though, to be attracted to earnest guys. In the fourth installment, “The First Time,” she remembers how the first guy she had sex with “always seemed too busy figuring out his counter-culture philosophy (which, of course, was total bullshit) to waste time with girls…” She finds that endearing. Why?

CLOWES: Just the idea that anybody would put himself on the line at all, by adopting an opinion that he’s actually serious about, instead of one of these sort of mock-opinions that people seem to have, I think is appealing.

HERMENAUT: But she hates people who are Serious, with a capital “S.” She makes fun of an activist friend of theirs, saying, “Yeah Jason, ever since you stopped eating meat and bathing and started doing graffiti and fucking up ATM machines, the world has become a way better place!” I love that. But then she goes on to say, about the Jasons of the world, “It’s not like these are just groovy, concerned people who actually care about humanity. It’s like the same as when guys are into sports!”

CLOWES: Right, that kind of activism is just a show-off kind of thing. It’s not about actual concern for someone else, it’s just a way of exuding your… “values-strength.”

HERMENAUT: Is the character Josh supposed to be an example of a “groovy, concerned” person? In the “Hubba-Hubba” installment, while she’s torturing the “bearded windbreaker” man, Enid asks Josh about his political beliefs, and he says, “I suppose I endorse policies that are opposed to stupidity and violence… cruelty in any form… censorship.” Are these meant to be political values we can take seriously, or is Josh just another overly sincere person?

CLOWES: In that instance, he’s speaking about the present circumstance he’s in, trying to make an issue out of the fact that what Enid’s doing is opposed to his way of thinking. He’s got a real love/hate thing with her, where he’s very attracted to her personality but is also repelled by her. He thinks she’s kind of shallow, and a “crazy girl.” He’s not a political type, but he’s the kind of guy who’s been teased all his life. He was the type of child who did not torture small animals, or pull the wings off of flies, and would have been horrified by that even then. He’s a gentle soul. Enid thinks of Josh as being the one decent human being in the world, because he’s a quiet person who keeps his opinions to himself.

HERMENAUT: So being an ironist like Enid does not preclude seriousness, as long as it’s a seriousness which does not take itself seriously. In fact, she seems to take things too seriously, a lot of the time, like these weird characters she collects: the psychic Bob Skeetes, the Satanist couple, the old bus stop guy she calls Norman. That’s what makes “The Norman Square” installment so tragic, because when Skeetes and Norman disappear, and the Satanists break up, and the pseudo-hipsters start hanging out at the un-cool diner because she’s made it cool, she’s devastated. The arch ironist is more emotionally vulnerable than other people, precisely because she’s worked to invest the crappy objects around her with meaning, and so she has more to lose.

CLOWES: Right! Enid has turned these people into kitsch, and loves them the same way she loves the bad comedian or the diner. The thing about the other kind of irony, the loveless David Letterman irony, is that it makes you totally invulnerable. You have nothing ever to lose, and therefore nothing has much of a charge to it, nothing’s really that interesting. It’s all just a sameness. Every day, it’s just another set of things to smugly look down on. You need to figure out a way to electrify things, instead.

HERMENAUT: By “electrify,” you don’t just mean “rebel against,” right? In fact, the only type of person Enid seems concerned to rebel against is the rebel. She never misses a chance to point out how much she hates pseudo-bohemian art-school guys who listen to reggae and the Grateful Dead, for example.

CLOWES: She hates that music exactly as much as I do! I live in Berkeley now, and every pizza place is blasting one or the other. I’ve always hated the Grateful Dead. I couldn’t even tell you what their music sounds like, that’s irrelevant. It’s the whole mentality that gives me the creeps. I never liked hippies at all. I grew up in-not quite a hippie family, but a family that was sympathetic to that kind of thing. When I was a little kid my older brother would have his hippie friends over and they’d smoke pot in my room and walk around naked, and at the time I just really disliked it. I was obsessed with Jack Webb [of Dragnet] when I was a little kid, and I agreed with his attitude about hippies — I still do.

HERMENAUT: What, specifically, do you dislike about hippies?

CLOWES: I think they generally have bad taste. I don’t like any of the things they like, their taste in art or music, or anything. I’m not even that crazy about the Beats, really. I like the idea of the Beats more than anything they actually wrote. I can relate to the whole ’50s anti-conformity thing, but then to go from that into abstract painting and cut-up poems… I find that stuff to be antithetical to the kind of work I like, which tends to be much more labor-intensive and which strives to communicate a concrete idea, rather than just throwing out impressions in the hopes that someone will “relate” to them.

HERMENAUT: Enid also rebels against her peers, people just like her: the hipsters and punks who hang out at the same record shops and zine stores she does. She despises the guy who publishes Mayhem, which is an Answer Me! type of zine all about serial killers, circus freaks, guns, and Nazis… but he also seems to be her friend. Because, like her, he seems to have this very self-conscious shtick, which he’s settled into, and he hates a lot of the same things she hates.

CLOWES: She feels some sort of vague kinship with him but then hates herself for it.

HERMENAUT: And then there’s this Johnny Apeshit character, who used to be a skinhead/anarchist type of punk, and now says stuff like, “I’m gonna be a big-ass corporate fuck! I’m gonna work for ten years, fuck things up from the inside as much as I can, and then retire when I’m thirty-five! That’s the way to be subversive…” He seems to represent another road Enid could go down, in her quest to rebel without being a “Rebel.”

CLOWES: That character is based exactly on a guy I went to school with, who was a hardcore punk when we were in college. I ran into him five years after that, and it was exactly that scenario, where he was going to business school but he was really trying to keep his “street cred” by saying he was only going to do it so he could “fuck everything up from the inside.” He struck me as the most pathetic person I had ever met.

HERMENAUT: So when you say that “you need to figure out a way to electrify things,” you mean something much grander, and also much more subtle, than rebellion-as-we-now-know-it. I like what Tripwire magazine says about Enid: “She turns the world around her into something glistening and different, something that’s big enough for her to be in.”

CLOWES: Right!

HERMENAUT: In the “Cavetown, USA” scene, Enid says she’s almost having a religious experience…

CLOWES: But not quite.

HERMENAUT: Unlike the “Jim Belushi-guys,” who aren’t even aware of the possibility of a religious experience, someone like Enid is constantly aware of the absence of such a state.

CLOWES: It’s very difficult to induce it. It comes when it comes. You just have to remain aware, keep yourself open to the possibility. You can have these experiences where you overhear someone talking about Bob Skeetes, and if you’ve made that event important enough, moments like that are these great highs. If you live without those moments, you’re always on some bland… mid-level.

HERMENAUT: At the end of “Chicago,” after detailing everything that’s wrong with that city, the narrator-you-say that “Chicago is a beautiful place; a dark and decaying testament to the sad beauty of bleakness and unfulfilled promises.”

CLOWES: Sounds like something I would write…

HERMENAUT: That’s a positive way of looking at the world that many people would not be able to recognize as such; it seems so negative.

CLOWES: “Chicago’s great because it’s bleak and horrible.” Yes, that’s exactly how I feel. You have to try to find a way to live, that’s what Ghost World is about. Enid finds a way to get up every morning, and she always finds something to do. That’s all you can hope for.

MORE CLOWES on HILOBROW: Joshua Glenn’s 1999 Q&A with Daniel Clowes | Joshua Glenn’s 2002 Q&A with Daniel Clowes | Josh also has an essay, “Against Groovy,” on Clowes’ anti-boomer ferocity, anti-hipsterism, apocalyptic fantasy, and trashy messianism, in The Daniel Clowes Reader.