10/40/70 synecdoche

By:

April 2, 2010

Earlier this week, at The Rumpus, Nicholas Rombes (who has written a contest-winning story for our sister site Significant Objects; and whose apocalyptic micro-story was a top-10 finalist in our latest Radium Age science fiction contest) read three frames of Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers in an aleatory fashion. Pausing the movie at the 10-, 40-, and 70-minute marks, Rombes claims to discover sufficient evidence to demonstrate that Verhoeven is an auteur who requires viewers to decide for themselves whether his 1997 Robert Heinlein adaptation is a satire or an endorsement of fascism; a critique or a celebration of war; an indictment or glorification of cruelty and bloodlust. Finding the whole in the part: synecdoche.

Synecdoche is a paranoid mode of interpretation — it’s employed brilliantly by Adorno, in Minima Moralia, for example when he claims that the difference between 20th- and 19th-century window-opening mechanisms reveals the violence lurking just beneath the surface of a supposedly advanced, progressive modern social order. But synecdochical and aleatory methods don’t mesh well. The latter (e.g., Rombes’ 10/40/70 trick) trust in chance, while the former are controlling in the extreme. What’s more, most attempts to employ synecdoche as an interpretive device aren’t nearly paranoid enough to pull off convincingly. I’m not disputing Rombes’ conclusion that Starship Troopers is a highly ambiguous text when it comes to political themes; he’s obviously correct. (Verhoeven has said that the movie’s message is: “War makes fascists of us all”; one wonders if that’s also true of the Starship Troopers first-person shooter video game?) But just as fascism (for Adorno) is a symptom of the dialectic of enlightenment, its political theme is merely one aspect of the movie’s overall dialectic — and not necessarily the most telling one.

Another aspect of the movie’s ambiguous overall dialectic — one which isn’t merely absent, but effaced from the 10-, 40-, and 70-minute scenes analyzed intelligently by Rombes — concerns gender. Although women do pilot spaceships in Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, in Edward Neumeier’s screenplay for the movie, women are portrayed as our future society’s dominant gender. Johnny Rico (Casper Van Dien) can’t compete academically with his girlfriend, Carmen Ibanez (Denise Richards), and she has more exciting career opportunities than he does. The quarterback of Johnny’s football team is “Dizzy” Flores (Dina Meyer); when the team showers together, a female player slaps Johnny on the ass.

Desperate to prove that he’s Carmen’s equal, Johnny joins the Mobile Infantry; the toughest member of the MI, however, turns out to be Dizzy, the only soldier tough enough to tackle the brutal Sergeant Zim (Clancy Brown).

And when Johnny and Dizzy hook up, she’s on top.

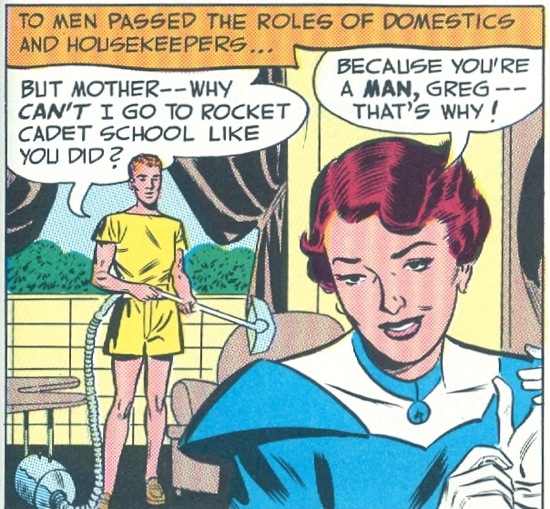

Starship Troopers is an intensely macho movie in which women are the macho-est of all. It’s as though Neumeier had mashed up Heinlein’s novel with John Broome’s 1952 Mystery in Space comics story “It’s a Woman’s World,” about which I posted last year.

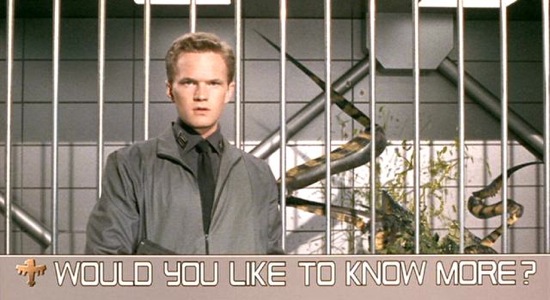

So what’s the ambiguous whole dimly glimpsed via these two synecdochical readings? What topsy-turvy dialectic, what rage against the social order and culture of the mid-1990s finds expression in Starship Troopers? Only Neil Patrick Harris knows for sure.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).