We Reabsorb & Enliven (5)

By:

March 25, 2010

When the battery came a cropper a few months after I purchased my first iPod, I was shocked to learn that there was nothing to be done. It’s one of our era’s familiar sensations. This sleek technological confection, like so many others, seems meant to be sucked dry of its juices and then discarded — only the latest and most flagrant iteration of the disposability that seems to be the telos of our tools. Unwilling to accept this fate (and too broke to spring for a new iPod), I went a-Googling for solutions. And I met another sensation familiar in these days: the welcome discovery that a hack exists. A mouse-click or two and a few days later a replacement battery had arrived, packaged with two plastic, vaguely dental tools designed to unstitch iPod’s seemingly seamless case. Painstakingly, clumsily, I applied the tools — and like a rip in the tissue of existence, the impregnable case cracked open to reveal the iPod’s tawdry innards, all microprinted serial numbers and vermiform wires. In so doing I had reconnected with our species’ ancient ways, our own tool-making, world-altering habitus; I had also voided my warranty.

This kind of debasement-by-design, this punishment of our wonted practicality, pains Matthew B. Crawford. It’s of a piece with so much else that seems to speak of decadence and infantilization: the digitization of automobile engines, the complexification of telephones and televisions (don’t try giving your spasming plasma screen that sharp rap one used to apply to a stuttering TV display). For Crawford, nothing serves as a better synecdoche for our despair than the disappearance of shop class from most high schools. There are technology high schools (where C. P. Snow’s “two cultures” of science and the arts are reduced to Excel and Photoshop, respectively), health professions high schools (medical billing and phlebotomy), even arts and performance high schools (polish your portfolio on YouTube!). But nowhere — certainly not among the blue states — is one likely to find adolescent Americans stooped placidly beneath the fluorescent lights working a solder gun, a torque wrench, or a tungsten-blade router with the kind of beatific attention that mechanical work requires. That’s how Crawford sees it; that’s how the followers of Ned Ludd once saw it as well. But that’s not fair to Crawford, who has got chops in both the shop and the seminar room; he’s a University of Chicago–trained political philosopher and a motorcycle mechanic. So before dismissing him as a crank with a crankshaft, it’s worth examining what he’s getting at in his first book, Shop Class as Soul Craft.

Here’s Crawford’s argument in brief: we’ve accorded respect and material rewards to those kinds of work that allegedly levy the greatest cognitive demands — the professions, certainly, but all kinds of white-collar work of managerial and administrative stamp as well. At the same time such work has grown in value, it has been degraded by double-talk, routine, and infantilization, to the degree that it fails to provide the mental stimulation that sustains happy engagement. Our manual trades, meanwhile, have been automated and robbed of social value, marginalizing young workers who feel their call. We feel our children pursue them only when they lose in the competition for places in the white-collar world. Crawford argues that society loses on both fronts: so-called knowledge work becomes a morass of diminished sinecures, while the honorable trades are tarnished. Regardless of the color of our collars, we increasingly lack chances to do work worth attending to — or taking pride in. Not only the product of our labor, but the quality of our working lives, suffers in the bargain.

Crawford resists the lure of nostalgia; he’s not tracing a corrupting historical process as much as he is anatomizing a disposition, one to which our technology-dependent culture easily falls prey. It’s not simply that with increasing automation we become further alienated from a world of tools and competence our forefathers took for granted. The “knowledge workers” of old were highbrows; they couldn’t shoe a horse or raise a barn any better than I can rebuild a carburetor, but the work they did was rich and challenging. Whether writing social novels or making history paintings or running parliaments, whether teaching classics or investigating natural history or crafting letters to faraway friends, highbrows of old did work that required lively and flexible minds. The so-called lowbrows meanwhile not only used tools, they often made them as well, suiting their technologies to novel problems; and the practice of the skilled trades today as ever requires minds as lively and flexible as those required of the actor, the architect, and the novelist.

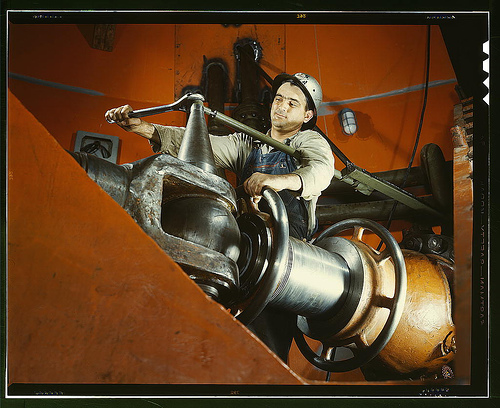

Today’s cognitive labor, however, is mechanized and simplified, broken down into flowcharts and algorithms. In an early chapter that’s a tour de force of popular intellectual history, Crawford traces the latter-day evolution of industrialization, showing how its effects now apply to the cubicle and the classroom as much as the factory floor. The first tradespeople to take jobs on the assembly lines rebelled at the enervating repetitiveness of the new factory work; today, industrial methods of business, teaching, and professional work have turned the office into a Dilbertian dystopia, a brightly lit abyss of alienation and self-loathing. “The new frontier of capitalism,” Crawford concludes, “lies in doing to office work what was previously done to factory work: draining it of its cognitive elements.” In the midst of this fluorescent wasteland, what’s the “spirited man” (or woman) to do? Crawford has an answer: cultivate the need for speed. Learn the ways of metal, oil, and electricity; plumb the mysteries of internal combustion.

For the speedway and the motorcycle repair shop have been Crawford’s salvation, as he tells us in loving detail. Emerging from a childhood spent in the effete realm of the vegetarians and mathematicians who were the adults of his childhood, Crawford found solace in shaping energies to the zero-sum requirements of building and maintaining Things With Engines. Exploring the motorhead’s dedication, he limns its deeply moral qualities — sustained attention on focal practices; subtle recognition of pattern and variation that comes with true mastery; easy and intimate familiarity with the idea of excellence. Crawford’s descriptions of his manual mentors and their skills as well as his précis of the philosophy of work and value offer lively and suggestive reading.

Shop Class as Soul Craft is as spirited as the way of life it recommends; its author is as quick with a quote from Anaxagoras as he is well versed in the ways of the spanner wrench and the voltmeter. Crawford doesn’t explore fully the deficits that the trades carry — how they need highbrows just as highbrows need them. The liberal arts are so called because they involve books; they’re neither above nor below but complementary to the manual arts, the trades. Traditionally, it was understood that society needed both in fruitful engagement with one another. Extolling the shopkeeper and craftsperson’s practical mien, useful skills, and satisfying labors, Crawford risks forgetting that the same set of dispositions can breed complacency and small-mindedness when turned to the work of making and maintaining a society.

We do well to follow the way outlined in Richard Sennett’s book The Craftsman (to which Crawford offers grateful acknowledgment). There, Sennett describes ways in which the moral disposition of the skilled trades offers a healthy approach to kinds of world-making work, whether pursued in the study, the cubicle, or the shop. We can lament our enervation — or we can make the tools we need to render our work and lives moral and meaningful. (Have you checked Google? The instructions required are probably available online.) There are skilled approaches to knowledge work, household work, and teaching work as well as to machine work; the spirited disposition Crawford celebrates should be brought to bear however one pursues a living. Failing a shop-class renascence, it may be our best hope.

A version of this essay appeared at the Barnes & Noble Review on June 26, 2009, in review of Shop Class as Soulcraft: an Inquiry into the Value of Work, by Matthew Crawford. It appears here as the fourth in a series revisiting Matthew Battles’ reviews for Barnes & Noble.