Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years’ War

By:

February 23, 2010

In 1756, the Duc de Richelieu (great-great nephew of the Cardinal), supported by twelve ships of the line under Roland-Michel Barrin de La Galissonière, the governor of New France, succeeded in wresting the recipe for what we now know as “mayonnaise” from 2,800 British troops dug in at the Port of Mahon, Minorca. It’s probable that the British on site didn’t even know that they had it — they had only taken possession of Minorca during the War of the Spanish Succession in 1708, and have never been known for their culinary perspicacity. The Duc led 15,000 troops in a siege of the capital, while Galissonière succeeded in driving off the British fleet under Admiral John Byng. Byng, by all accounts supplied with sub-par and poorly armed ships, took heavy damage on his initial sally and withdrew without damaging the French fleet. On returning home his “failure to do his utmost” led to his court-martial and execution, carried out over the objections of William Pitt. This last fact does seem to suggest that at the highest levels of British government, the loss of the recipe was greatly felt, for history has long wondered at the disproportionate response to Byng’s failure. Even Voltaire took note of it in Candide (1759), saying “Dans ce pays-ci, il est bon de tuer de temps en temps un amiral pour encourager les autres.” (“In this country, it is wise to kill an admiral from time to time to give courage to the others.”)

This was the first European battle of a conflict that had hitherto been confined to North America (and known here as the French and Indian War). It’s now apparent that France, seeing Britain’s fortunes turning (their alliance with Austria had just fallen apart and they had only Prussia aligned against France, Austria, Russia, Sweden, and Saxony), had taken the opportunity to make a run for what the Spanish/Catalan architects of the sauce called salsa mahonesa. Allioli had been around at least since Pliny wrote about it in the first century C.E., but it had always been extremely problematic — coaxing an emulsion out of oil, garlic, and salt is, it is almost universally agreed, nearly impossible. This process had remained a Catalan secret for millennia for just this reason — it could hide in plain sight because it was the culinary equivalent of black magic. What had apparently happened at some point (probably during the Renaissance) was that someone had added an egg and an acid to the recipe. This changed everything — anyone with the simple, if unlikely, instructions could now make this wonderful sauce. War was inevitable.

If some of this seems unlikely, consider that in French cuisine there are only seven “mother sauces” the sauces from which all other sauces are made. Only two of these sauces are cold — mayonnaise and vinaigrette, with mayonnaise by far the more crucial — and all of them are French in origin. Except mayonnaise. Even the mother sauce espagnole (meaning Spanish in French) has nothing to do with the Spanish (like the secondary sauce, sauce allemande — German sauce — so named because it’s yellow). This also explains why they never incorporated aioli, the great garlic/egg/oil emulsion from Provence, surely the son of allioli and the cousin of mayonnaise. Provence is not France, at least not as far as cuisine goes, and they never would have been able to cover that up.

If the story had ended here, it would be an amusing footnote to culinary history — France and Britain were going to get into it at some point, the fact that the precipitating incident was the seizure of the recipe for salsa mahonesa (sort of the arch-duke Ferdinand of the Seven Years War) is interesting, but it’s the cover-up that is really astounding.

The first story was that the Duc’s personal chef invented mayonnaise on the spot upon realizing that there was no creme to make a sauce to celebrate the Duc’s victory at Minorca — he named it mahonnaise to celebrate the occasion, but it was Frenchified soon after their triumphant return home. Somehow this story, which even in the history of folklore of the kitchen stands out for its ludicrousness, still gets passed around occasionally. The Duc actually has his own sauce (not to mention a sponge cake) made with onions fried in clarified butter, consommé, nutmeg, chervil and, allemande sauce, as well as a reputation as a gourmand. This last fact certainly helped in the selling of this silly story, and was probably why he was chosen to lead the attack in the first place. Interestingly, this is the only story that includes mention of the sauce’s actual name — mahonesa. More telling than the story itself, was the mention of the Duc’s personal chef on a major amphibious operation. Doubtless, Louis XV (or whoever was behind l’affair mayonnaise) had insisted that the invasion force include a chef to test the veracity of the recipe.

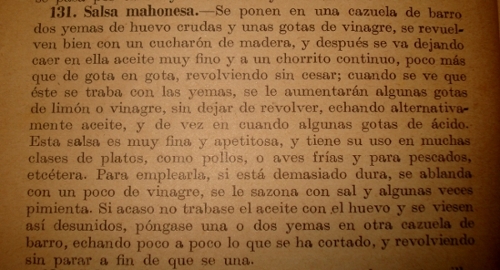

Salsa mahonesa.— Se ponen en una cazuela de barro dos yemas de huevo crudas y unas gotas de vinagre; se revuelve bien con un cucharon de madera, y despues se va dejando caer aceite muy fino y á un chorrito continuo, poco más que de gota en gota , en ellas, revolviendo sin cesar; cuando se ve que éste se traba con las yemas, se le aumentarán algunas gotas de limon ó vinagre, sin dejar de revolver, echando alternativamente aceite, y de vez en cuando algunas gotas del ácido. Esta salsa es muy fina y apetitosa, y tiene su uso en muchas clases de platos, como pollos ó aves frías, y para pescados, etc. Para emplearla, si está demasiado dura, se ablanda con un poco de vinagre, se la sazona con sal y algunas veces pimienta. Si acaso no trabase el aceite con el huevo, y se viesen asi desunidos, pónganse una ó dos yemas en otra cazuela de barro, echando poco á poco lo que se ha cortado, y revolviendo sin parar, á fin de que se una.

Salsa mahonesa — Put two raw egg yolks in an earthenware pot with a few drops of vinegar, stir well with a wooden spoon, after which drop the oil in a very thin, steady stream, little more than drop at a time, stirring constantly, when you see that the yolks are becoming thick, you add a few drops of lemon juice or vinegar, stirring, pouring oil alternately, and occasionally a few drops of acid. This sauce is very fine and tasty, and is used in many kinds of plates like chickens or cold birds, and for fish, etc. To use it, if it is too harsh, it is softened with a little vinegar, seasoning it with salt and pepper sometimes. If the oil and the egg breaks, and they become disunited, take one or two yolks in another earthen bowl, pouring little by little the broken mayonnaise, and stir without stopping, until they are reunited.

It’s unclear if, at the start, the aim was to claim a French genesis for mayonnaise, or to obscure the fact that some fifteen thousand men and twelve ships of the line were sent to Minorca to procure it. As time passed though, the emphasis tipped towards the latter, until the outright destruction of the Spanish claim was the goal. We’ll look briefly at the most famous misdirections:

¶Bayonnaise: The sauce was discovered in the town of Bayonne but later became “corrupted” to mayonnaise.

Clearly this would make more sense the other way around as any French person is perfectly familiar with Bayonne, an ancient and reasonably large and famous city in Basque country. There is a Bayonne version of mayonnaise (just as there is a Dijon version), though.

¶Moyeunaise: Prosper Montagne, creator of the great Larousse Gastronomique, claimed that the name was derived from moyeu, and old French word for yolk. This has the benefit of seeming both plausible and scholarly, but, regrettably, appears to have no other basis. Its repeated appearance in editions of Larousse has granted it longevity, if nothing else.

From: The pleasures of the table: an account of gastronomy from ancient days by George Herman Ellwanger, 1902:

Magnonnaise: This Careme has dealt at length with in his treatise on cold sauces. The origin of the word mayonnaise, a blending supposed to be the invention of the Marechal de Richelieu has remained in doubt. Its etymology has been [traced] to Mahon a town of southern France yet this supposed derivation is extremely dubious and, as it also known as bayonnaise it might belong equally to Bayonne, famous for its hams its cheese and its chocolate and for having invented the bayonet (footnote: All the entrees having the name Bayonnaises a corrupt term for Mahonnoise were the invention of the Marechal Duc de Richelieu Manuel des Amphitevons

It has been variously termed mahonaise, bayonnaise, mahonnoise, magnonaise, and mayonnaise, but Carême after minutely describing its preparation from the first drop of oil to its final silky white and unctuous cream denies its accepted derivation and pronounces it magnonaise from the verb manier to stir, as it may be prepared only through the continual stirring it undergoes which results in a marrowy velvety and very appetising sauce unique of its kind and bearing no resemblance to others that are obtained only through reductions of the range. Despite this ingenious explanation the word is still written mayonnaise and while lights shine brilliantly and champagne sparkles and the great crawfish sublimated into salad receives the encomiums of appreciative guests the famous chef of the Empire is forgotten and the chapter of the Cuisinier Parisien exists only as a tale that is told.

Carême, the most famous chef of the 19th century and perhaps of all time, gives it a good try here. His name recognition has certainly kept the story alive, but there’s not any real basis for his derivation which seems, like moyeu, to be wishful thinking. I’m especially charmed by the description of Mahon as a town in southern France and the conflation of mahonnaise and bayonnaise so that they are both the Duc de Richelieu’s fault.

¶McMahonaise: This last I mention only as an entertaining side note (and as one of Irish extraction myself), but the Irish did try to claim the recipe by attributing it to a McMahon.

At the end of the Seven Years War, in 1763, Minorca was conveyed back to Great Britain in exchange for Guadalupe. Britain also received most of the French lands in North America, including everything French west of the Mississippi. Unbeknownst to everyone (including the inhabitants of Louisiana and the French Canadians making their way there) the French had ceded Louisiana to Spain in the previous year’s Treaty of Fontainebleau. Often viewed as a clever stratagem to keep Louisiana out of the hands of the British, it seems more likely that the gift secured Spanish silence on the mahonnaise subject. The Spanish (after putting down a revolt of disenfranchised French peoples — put down, I should note, by the Spanish governor, Irishman, Alejandro O’Reilly) immediately began work on a cajun rémoulade recipe (mayonnaise, gherkins, parsley, chives, chervil, tarragon, capers, anchovy essence, paprika and cayenne).

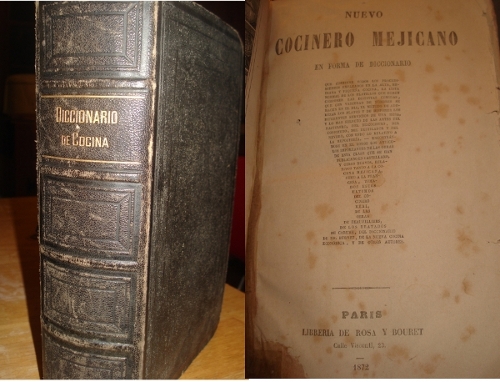

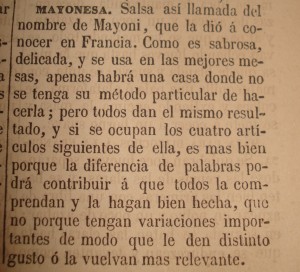

The recipe shown above for “salsa mahonesa” is from a Spanish/Mexican cookbook published in Mexico. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was common for Spanish language cookbooks, both Spanish and the newer efforts to document Mexican cuisine, to be published in Paris, like this cookbook from 1872:

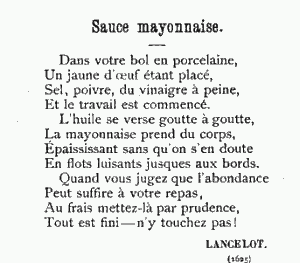

This poem is pretty remarkable — folded into an 1891 Spanish culinary almanac, it poetically describes the creation of a mayonnaise as if it were the most quotidian of creations, and was dated 1625. Attributed falsely to “Lancelot” (presumably intended to be Lancelot de Casteau, author of Ouverture de Cuisine, Paris, 1604), it was actually written by Achille Ozane (after a poem by René-François Sully Prudhomme, titled “Le vase brisé“) and collected in Poésies Gourmandes, 1900. The French had a long history of food poetry — Les Soupers de Momus, for example, was a yearly collection that stretched decades of the early 19th century — so there was a built-in inclination to believe this sort of thing. Extremely clever, of course, was the planting of this seed in a Spanish publication so its origin (no French speaker would mistake this for a 17th-century poem) wouldn’t be questioned. Years later the truth was discovered, but the psychological damage was done. Today you’d be hard pressed to find even a Minorcan who believes that the Spanish invented the great salsa mahonesa.