That’s Entertainment

By:

February 10, 2010

No matter how you feel about curling (up or otherwise); no one, it seems, has time to read a book. I don’t even have time to read a magazine — and never mind the articles. Books, like fine art before them, have receded from the intuitive adjustments of the quotidian. One needs to make a differentiated, focused effort to concentrate on reading, quite apart from one’s daily life. Like art set aside in a gallery or museum, and requiring a special visit; now books too require a special gallery of attention in your mind. You must set aside time, and set aside space, and of course set aside the internet so you can’t just check your messages or update Twitter in between chapters. Or — who are we kidding — in between pages. We’re getting our entertainment — or news, or information, or even our meditative moments — here and there, interspersed throughout the day, while doing other things.

Our short attention spans provoke much lamentation, but it’s really nothing new. According to a PBS documentary on vaudeville, an act was viable if it could manage to keep the audience’s attention for three minutes. Three minutes!! That’s a span we understand — approximately the length of the average YouTube video, or a popular song.

[Rain Steam and Speed, The Great Western Railway, J. M. W. Turner, 1844]

People have been complaining about the speed and fragmentation of modern life since well before there was a “modern” to complain about. And now that we’ve become modern, or even post-, it’s faster and more fragmentary than anyone anticipated, and looks to be going ever further in that direction.

[Robert Downey Jr. as a naked metaphor in Sherlock Holmes, dir. Guy Ritchie, 2009]

But wait — maybe this is not bad. This is not good versus evil going 40 rounds for the title. This, I would suggest, is something altogether more neutral, more technological. Fragmentation and absorption are models of interaction. And like all models they invite other perspectives.

For example, consider a book. A nice, long book with hundreds of pages, one so good you don’t want it to end. You are completely immersed, looking forward to the end of the day when you can lose yourself in it again, staying up past your bedtime for just a few more pages. Good, right? Our lost Eden, right? But now consider: what may be absorption and focus from one angle could be irresponsible escapism from another. What are you doing with yourself while reading that book? Hiding from your surroundings, spending hours of time immobile, emerging to measure real things in your life by the imaginary story? Replace “book” with “internet” and this looks a lot like addiction.

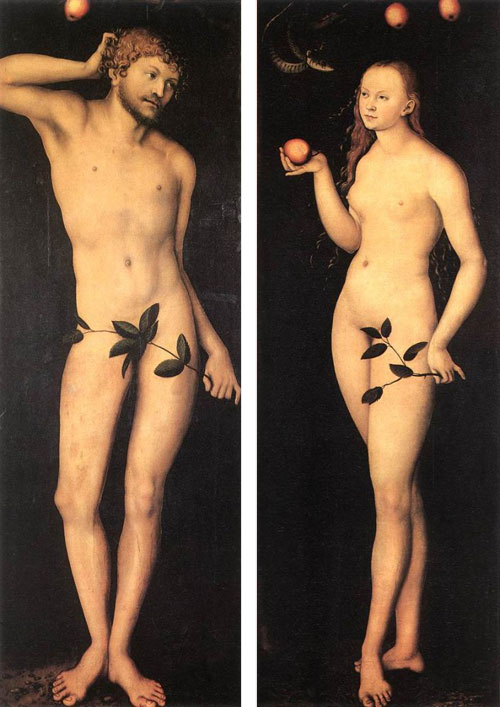

[Adam and Eve, Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1528]

Now consider a Facebook game like FarmVille, or a Twitter novel, or a film or series broken up into short YouTube segments, perfect for viewing in a corner of your screen at work. What may be fragmentary and distracted frittering from one point of view, might also be a way to integrate the experience of art into everyday life. When I lived in Berlin a few years back, there were microfilms in the subway cars. Instead of dead time, undead time: the vampire entered screen left, accepted the beautiful woman’s challenge to play chess, achieved checkmate, bared his fangs and then disintegrated! as the sun came up and the film ended and the doors opened and we all got out.

I’m not advocating a complete replacement of long with short, nor am I claiming, with Pangloss, that “all’s for the best in this best of all possible worlds.” But I am saying these are models of interaction, and there’s often more than one way to look at a model.

[Overture to Candide, composed and conducted by Leonard Bernstein]

In addition, there’s often a future concealed within the fragment. For example, FarmVille: you check in every day for weeks, maybe months, as you tend your virtual 2.5D farm with your friends. It’s not a narrative but it is a persistent relationship. Or Twitter novels, which are narratives; in other words, small increments, doled out consistently over long periods of time can accumulate to — in some cases — significance? There are gaps. But we fill them in ourselves. As we do with everything.

Even the truly molto largo can be sampled in bits. Yes, it’s better if you can devote several hours to the whole thing. But here I give you the opening snippet of Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror, to infiltrate the next 8 minutes of your everyday:

[The Mirror, dir. by Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975]

[Early vaudeville photo from the collection of Bob Bragman, as featured in the San Francisco Chronicle]