Radium-Age Robots

By:

January 30, 2010

During science fiction’s Radium Age, writers dreamed up mechanical and quasi-organic humanoids so compelling that they continue to haunt today’s sf, forcing us to ask what it means to be human.

[A version of this item first appeared on Gawker’s sci-fi blog io9.com, on Jan. 12, 2009. The first episode of HiLobrow.com’s podcast, “Parallel Universe: Pazzo,” features readings from six Radium Age Robot stories; listen to it here.]

Forget WALL-E and GORT. Forget sexy Summer Glau and Tricia Helfer in Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles and Battlestar Galactica. OK, don’t forget them. But check it out: Long before Autobots, Fembots, and the Urkelbot, Radium Age SF authors obsessed over electricity-, steam-, and clockwork-powered machine-men or “robots” (a term introduced in 1921) that might free us from the burden of labor… or else run amuck and destroy/enslave us. Before Yul Brynner, Daryl Hannah, and Brent Spiner played troubled biomechs, replicants, and skin-jobs in Westworld, Blade Runner, and Star Trek: TNG, SF novels and stories published from 1900-35 (roughly) asked what, exactly, distinguishes an “android” — a term, meaning “human-like,” first popularized in an 1886 French SF novel — from one of us? And before the Six Million Dollar Man, the Terminator, and the Borg popularized the obscure 1960s notion of the “cyborg,” Radium Age SF authors had already inserted human brains into machines, and vice versa, creating existential crises of every variety for their characters.

Here’s a list — in no particular order — of 10 of the most compelling and uncanny robot, android, and cyborg-oriented novels, stories, and plays that were published in the decades immediately before SF’s so-called Golden Age. There’s a more complete list at the end, too. Suggestions, criticisms welcome!

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

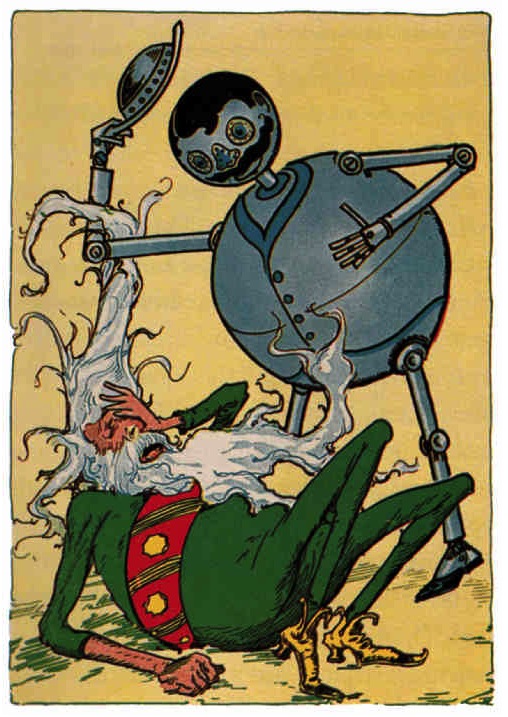

1) L. Frank Baum, Ozma of Oz (Chicago: Reilly & Britton, 1907). The third Oz book, and the first in which we meet one of Baum’s most delightful characters: “He was only about as tall as Dorothy herself, and his body was round as a ball and made out of burnished copper. Also his head and limbs were copper, and these were jointed or hinged to his body in a peculiar way, with metal caps over the joints, like the armor worn by knights in days of old.” From a printed card attached to its neck, Dorothy learns that Tiktok is a “Patent Double-Action, Extra-Responsive, Thought-Creating, Perfect-Talking Mechanical Man Fitted with out Special Clock-Work Attachment. Thinks, Speaks, Acts, and Does Everything but Live.” Though one of the earliest fictional appearances of true machine intelligence, Tiktok (above, with Nome King) is not a free agent like his (equally metallic, yet living) new friend, the Tin Man, to whom he confides that “When I am wound up I do my du-ty by go-ing just as my ma-chin-er-y is made to go.” Fun fact: Baum revisited this story for his 1913 musical, The Tik-Tok Man of Oz, in which Tiktok sings: “Always work and never play!/Don’t demand a cent of pay!”

READ IT | OZ IMAGES

LISTEN TO HILOBROW’S PODCAST VERSION

2) Karel Čapek, R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots (1921 premiere as R.U.R.: Rossumovi univerzální roboti; in translation, 1923). This surreal morality play takes place in the 1960s or so, and it’s set in the factory of a (USA?) manufacturing concern that has shipped hundreds of thousands of “Robots” — biological humanoids designed for cheap labor — around the world. (We’d call Čapek’s Robots “androids,” now; see Spock-like sketch of one from the ’22 New York production, above.) The Robots, which have a limited life span, are supposedly soulless. Not so, claims Helena Glory, a liberal activist who marries the factory’s GM (who envisions a utopia in which humans won’t have to do any work). At Helena’s urging, R.U.R.’s scientists develop Robots tricked out with extra humanity… at which point they rise up and exterminate humankind. In an epilogue, Alquist, R.U.R.’s construction engineer and the last surviving human, give his blessing to two new-model Robots, Primus and Helena, who have discovered love. Warning them to avoid the sins that destroyed his own species, Alquist sends them forth to be fruitful and multiply. Fun fact: The term robot, coined by Čapek’s brother, Josef, comes from the Czech for “serf labor.”

READ IT | R.U.R. IMAGES

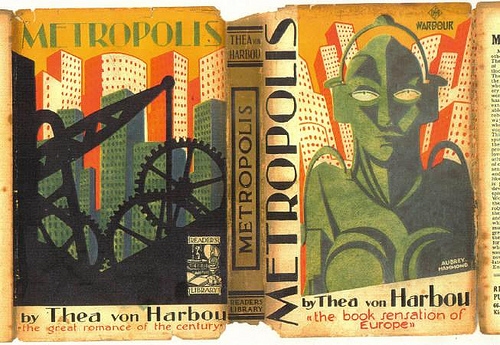

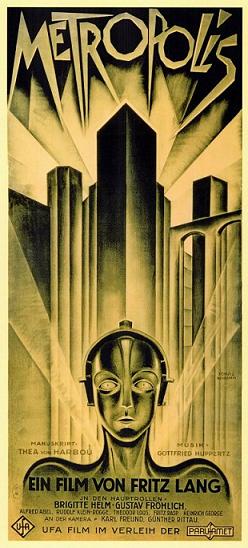

3) Thea von Harbou, Metropolis (1926; in translation, 1927). Set in a dystopian city-state, this Expressionist novel asks us to imagine a perverse synthesis of the era’s seminal dichotomy: Henry Adams’s dynamo-vs.-virgin question. Metropolis’s Pharaonic master, Joh Fredersen, deplores those weaknesses that make his dehumanized laborers (they wear standard uniforms, and answer to numbers) inferior to machines. So he orders the mad inventor-magician, Rotwang, to build him “machine men.” Instead, Rotwang constructs an alluring female-shaped machine whom he names Parody, or Futura: “The being was, indubitably, a woman… But, although it was a woman, it was not human. The body seemed as though made of crystal, through which the bones shone silver.” After rendering Futura’s face in the exact likeness of Maria (a flesh-and-blood woman who is both the conscience of the rebellious workers and the object of Fredersen’s pinko son’s affection), the villainous technocrats program their synthetic Virgin/Dynamo to act as an agent provocateuse. The workers revolt, and Futura/Maria is destroyed. But in the end, the Virgin (sentimental religiosity) triumphs over the Dynamo (technology-driven development). Hooray? Fun fact: Von Harbou and her husband, film director Fritz Lang, developed the scenario for Metropolis, then she wrote the novelization while he directed the brilliant 1927 movie.

LEARN MORE | READ IT

LISTEN TO HILOBROW’S PODCAST VERSION

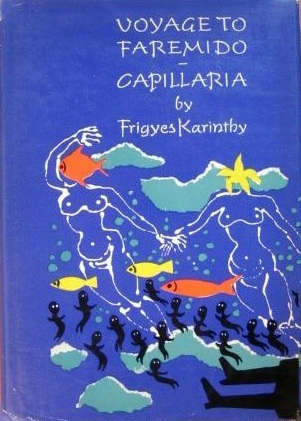

4) Frigyes Karinthy, Voyage to Faremido: Gulliver’s Fifth Voyage (Utazás Faremidóba; Gulliver ötödik útj, 1916; in translation, 1965). It’s 1914, and Jonathan Swift’s Lemuel Gulliver is eager to go to sea again. He signs on as a surgeon on a British ship, only to be torpedoed in the Baltic, then picked up by a UFO and transported to Faremido, a planet ruled by intelligent machine-folk. They regard organic life as a loathsome disease of matter, so they’re tickled about the Great War, which looks likely to exterminate humankind. Agreeing that the Faremidoans (whose society is peaceful, and whose fa-re-mi-do language is musical) are superior beings, Gulliver accepts an injection of their own brain-matter — quicksilver and minerals — into his head. Now a proto-cyborg himself, Gulliver is sent back to England, where he finds it difficult to adjust to the irrational horrors of everyday life. Fun fact: The sequel to this Hungarian novella is Capillária (1921), in which Gulliver gains insight into sexual politics when he visits a submarine civilization whose women dominate and eat their menfolk. Also see Karinthy’s recently reissued autobiographical novel, A Journey Round My Skull.

BUY IT | READ IT (HUNGARIAN)

5) S. Fowler Wright, “Automata: I-III” (Weird Tales, September 1929). The first episode of this three-part series — by the British author of The Amphibians, Deluge, and Dawn — is set in the present or near future. Addressing the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the distinguished scientist Dr. Tilwin announces that humankind’s prerogatives will soon be taken over by machines, which are already superior to us in certain ways. Intelligent machines are omnipresent in the second episode, set at some point after the 20th century. By this time, human procreation has almost stopped (Wright, a would-be Wellsian social prophet, was a fierce critic of birth control) and children are increasingly rare. In the final episode, one of the last humans on Earth is drawing a picture — one of the few tasks that machines can’t perform, because it requires imagination. Alas, because he doesn’t properly finish his assignment, he is condemned to be executed. Fun facts: Robots didn’t come hardwired with systems of ethics until Isaac Asimov and John W. Campbell made it so in the ’40s. Also, Wright translated Dante’s Inferno and Purgatorio.

ABOUT SFW | BUY SFW BOOKS

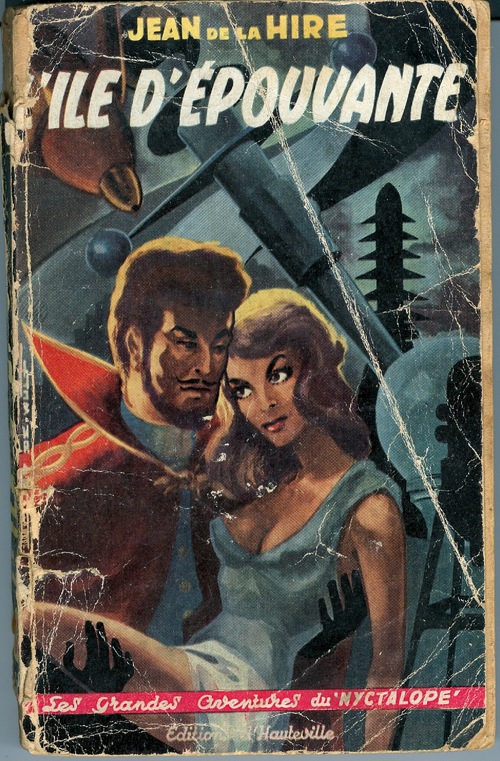

6) Jean de La Hire, The Nyctalope on Mars (Le Mystère des XV, 1911). Léo Saint-Clair, alias the Nyctalope, is an indomitable Doc Savage-style crimefighter gifted with night vision. As we learn somewhat late in the series, he’s also equipped with an artificial heart, which he gained after being tortured and nearly assassinated, and which prevents him from aging. In this, the first of a series of exploits published through the mid-1940s, the Nyctalope — pictured above, in a different adventure — battles Oxus, leader of the sinister Society of the Fifteen, who is plotting to conquer Earth from his secret base on Mars. Later, however, he allies himself with Oxus and the planet’s benign inhabitants in order to defeat H. G. Wells’ evil Martians. Then he gets married. Phew! In subsequent SF adventures, the Nyctalope will travel to the planet Rhea, where he’ll end a war between the day- and night-siders; discover a lost civilization of Amazons in Tibet; and have himself cryopreserved so that, 170 years later, he can defeat an enemy who has also been frozen (hello, Demolition Man and Austin Powers). A pioneering pulp superhero and cyborg. Fun fact: Nyctalopia is a real medical condition that causes you to see poorly — or well — in the dark.

LEARN MORE | BUY THE 2008 ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION

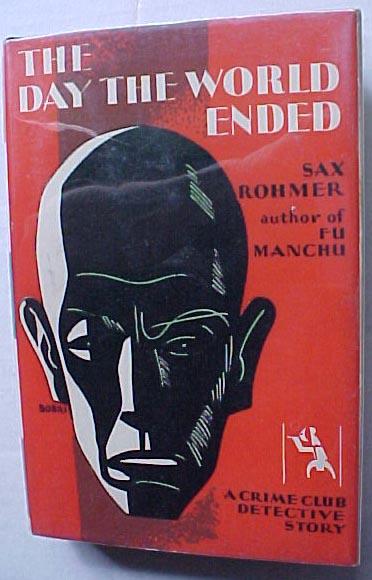

7) Sax Rohmer, The Day the World Ended (London and New York, 1930). Three international crimefighters — Lonergan, an American secret service agent; Gaston Max, a dandified French police detective; and Brian Woodville, an English journalist — are investigating a series of strange events: radio silence in the USA, reports of man-bats in the Black Forest, the sudden death of everyone in a French village. It turns out that Anubis, a dwarfish evil genius, is plotting to establish a utopian society populated by surgically altered and highly conditioned humans (i.e., androids). How? By destroying the rest of the Earth’s population with a sonic weapon. The trio infiltrate Anubis’s German castle, populated by 7-foot-tall guards and “soulless” houris — hello, Westworld and Stepford Wives — and call in an air strike. Fun fact: Rohmer was best known for his (racist) thrillers about Dr. Fu Manchu.

BUY IT | ABOUT ROHMER | READ ROHMER |

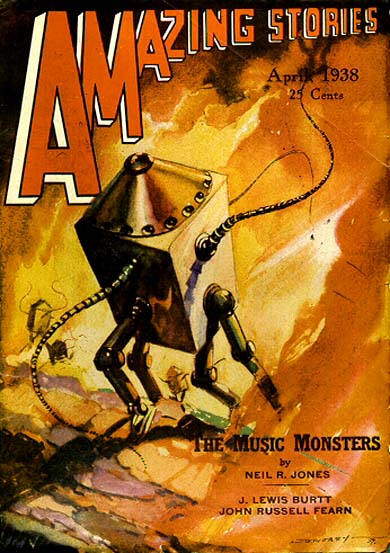

8) Neil R. Jones, “The Jameson Satellite” (Amazing Stories, July 1931). In 1958, Professor Jameson arranges for his body to be cryopreserved — in a rocket orbiting the Earth — after he’s dead. Forty million years later, a crew hailing from the planet Zor, whose inhabitants had “built their own mechanical bodies, and by operation upon one another had removed their brains to the metal heads from which they directed the functions and movements of their inorganic anatomies,” discover the satellite. The Zoromes transfer Jameson’s brain into a machine body, then take him to visit the lifeless Earth, an experience that nearly drives him mad, until he realizes that “He could be immortal if he wished! It would be an immortality of never-ending adventures in the vast, endless Universe among the galaxy of stars and planets.” Indeed, Jones would publish 21 more “Professor Jameson” stories; cover illustration for 2d installment, at left. Fun fact: Isaac Asimov claimed the Zoromes, who are thoroughly objective, gave him his “feeling for benevolent robots who could serve man with decency.”

READ IT | BUY THE BOOKS

LISTEN TO HILOBROW’S PODCAST VERSION

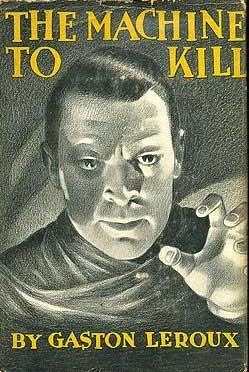

9) Gaston Leroux, The Machine to Kill (1924 as Le machine à assassiner; 1935 translation). France’s top police detective, Lebouc, is on the trail of a human-looking mechanical man (pictured at left) whose skull houses the brain of Benedict Masson, a guillotined murderer. Animated with radioactive serum, the cyborg — named Gabriel by its creator, a clockwork expert named Norbert — has carried off Norbert’s daughter, Christine. She’s the one who witnessed Benedict burying a corpse in his basement… so does Gabriel/Benedict want revenge? And what’s with the Hindu vampire cult that kidnaps Christine — did they commit the murders for which Benedict died? G/B is captured by Lebouc, but escapes and rescues Christine from the cultists before destroying itself by leaping into a river. The End? No! Christine, who has fallen in love with the cyborg, reassembles G/B’s remains, and prepares to reanimate it… only to discover that her husband has destroyed its brain. Fun fact: Leroux is best known for his 1910 horror tale, Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, on which the movies and Broadway show are based.

READ IT (FRENCH) | MORE LEROUX

10) W.K. Mashburn, “Sola” (Weird Tales, April 1930). Though he despises women and can’t stand their company, Dr. Franz Dietrich desires them sexually. So he invents a flesh-like substance, which a sculptor helps him shape into a gorgeous female android. Having wired Sola with complex responses — the apparatus is supposed to react in particular ways, immediately upon perceiving his telepathically projected emotions — the mad scientist invites a group of colleagues over to dinner. Growing tipsy, Dietrich flies into an embarrassed fury, because he thinks Sola is unresponsive, and tries to destroy it. But his colleagues — and eventually, the entire town — pitch in to raise his self-esteem by treating Sola as a member of the community. Oh wait, I’m thinking of Lars and the Real Girl. What actually happens is that Sola’s emotion receptors are activated by the professor’s rage, and his own creation crushes him to death. A classic example of what McLuhan — in The Mechanical Bride (1951) — would call “the curious fusion of sex, technology, and death.”

MORE RADIUM AGE ROBOTS

NINETEENTH CENTURY (1804-1903)

* E.T.A. Hoffmann, Der Sandmann (1814) — lifelike clockwork

* Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (1818) — human, assembled and reanimated

* Edgar Allan Poe, “Maelzel’s Chess Player” (1836) — Poe disputes machine intelligence

* Edgar Allan Poe, “The Man That Was Used Up” (1843) — human, artificial body

* Nathaniel Hawthorne, “The Artist of the Beautiful” (1844) — mechanical butterfly

* Herman Melville, “The Bell Tower” (1855) — automaton bell-ringer comes to life?

* Edward S. Ellis, The Steam Man of the Prairies (1865) — man-shaped engine

* H. D. Jenkins, “The Automaton of Dobello” (1872) — 14th-century automaton as ghost

* Julian Hawthorne, “An Automatic Enigma” (1878) — human disguised as automaton

* E.P. Mitchell, “The Ablest Man in the World” (1879) — Babbage’s analytical engine in head; first cyborg?

* Jacques Offenbach, The Tales of Hoffmann (1881) — lifelike clockwork

* Don Quichotte, “The Artificial Man: A Semi-Scientific Story” (1884) — human, artificially grown

* Luis Senarens, Frank Reade and His Electric Man (1885) — electricity-powered mecha?

* Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve (1886) — popularized “android”

* Howard Fielding, “Automatic Bridget” (1889) — robot housemaid amuck

* Cyrus Cole, The Auroraphone (1890) — humanoid “dummies” rebel

* William Douglas O’Connor, “The Brazen Android” (w. 1857, p. 1891) — steam-powered mecha? First steampunk?

* Jerome K. Jerome, “The Dancing Partner” (1893) — dancing robot amuck [LISTEN TO OUR PODCAST]

* M.L. Campbell, “The Automatic Maid-of-All-Work” (1893) — robot housemaid amuck

* G.H.P., The Artificial Mother: A Marital Fantasy (1894) — robot nursemaid amuck

* Elizabeth Bellamy, “Ely’s Automatic Housemaid” (1899) — robot housemaids amuck

* Gustave Le Rouge & Gustave Guitton, The Billionaire’s Conspiracy (1899-1900)

* Harle Oren Cummins, “The Man Who Made a Man” (1902)

THE NINETEEN-OUGHTS (1904-13):

* H.P. Fitzgerald Marriott, The Iron Detective of Germany: A Comedy of the Near Future (1908)

* Ambrose Bierce, “Moxon’s Master” (1909) [LISTEN TO OUR PODCAST]

* Henry A. Hering, “Mr. Broadbent’s Information” (1909)

* Charles Hannan, The Electric Man (1910)

* J.H. Rosny aîné, La Mort de la Terre [The Death of the Earth] (1910) — the emergence of a new species, the metal-based “Ferromagnetals” (not robots)

* Edgar Rice Burroughs, The Monster Men (1913, 1929)

* Jacob Epstein’s sculpture “Rock Drill” (1913)

THE TEENS (1914-23):

* L. Frank Baum, Tik-Tok of Oz (1914)

* Luigi Pirandello, Shoot: The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator (1915), whose protagonist ends by not knowing where his body ends and the machine he operates begins: “I cease to exist. It walks now, on my legs… I form part of its equipment.”

* Jean Metzinger, painting, “At the Cycle Race Track” (1914)

* Perley Poore Sheehan & Robert H. Davis, Blood and Iron (1917)

* Jean de La Hire, Lucifer (1921-22)

* Jean de La Hire, Le Roi de la Nuit (1923)

* E.V. Odle, The Clockwork Man (1923)

THE TWENTIES (1924-33):

* John Lionel Tayler, The Last of My Race (1924)

* Jean de La Hire, L’Amazone du Mont Everest (1925)

* Ivan Narodny, The Skygirl, A Mimodrama (1925)

* Edmond Hamilton, Across Space (1926)

* Edmond Hamilton, The Metal Giants (1926)

* Jean de La Hire, L’Antéchrist (1927)

* Maurice Renard & Albert Jean, Blind Circle (1925)

* David H. Keller, “The Psychophonic Nurse” (1928)

* Edmond Hamilton, The Comet Doom (1928)

* Amelia Reynolds Long, “The Twin Soul” (1928)

* Francis Flagg, The Chemical Brain (1929)

* Jean de La Hire, Titania (1929)

* Stephen Leacock, “The Iron Man and the Tin Woman” (1929)

* William Salisbury, The Squareheads (1929)

* Jean de La Hire, Belzébuth (1930)

* Otis Adelbert Kline, The Prince of Peril (1930)

* Ainslee Jenkins, “Men of Steel” (1930)

* Abner J. Gelula, “Automaton” (1931)

* Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (1932) — maybe

* Jean de La Hire, Gorillard (1932)

* John Wyndham, “The Lost Machine” (1932)

* David H. Keller, Revolt of the Pedestrians (1932)

* Neil R. Jones, “The Planet of the Double Sun” (1932)

* Neil R. Jones, “The Return of the Tripeds” (1932)

* Jean de La Hire, L’Assassinat du Nyctalope (1933)

* Jean de La Hire, Les Mystères de Lyon (1933)

* Neil R. Jones, “Into the Hydrosphere” (1933)

* Neil R. Jones, “Time’s Mausoleum” (1933)

* J. Storer Clouston, Button Brains (1933)

PLUS:

* Harl Vincent, “Rex” (1934)

* A. Merritt, “The Last Poet and the Robots” (1934) [LISTEN TO OUR PODCAST]

Not included: myths (the Golem, Pygmalion) or fantasies (L. Frank Baum’s Tin Man) where no attempt at achieving scientific verisimilitude, however feeble, is made. Also: I have mostly left automatons (or mecha) — defined as mechanical apparatuses programmed or devised to do certain operations that rely on control from outside; no possibility of independent action — off this list.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE