The Kibbo Kift & the Usable Past

By:

January 7, 2010

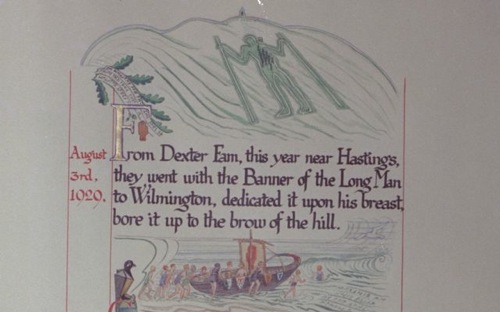

A prehistoric track stretches across 250 miles from the Dorset coast to the Norfolk Wash. For over five thousand years, people have walked or ridden this trail. The first section we know as the Ridgeway, a chalk ridge beginning in the uplands of Wessex and bisected by the River Thames at Goring Gap, rising above the low ground and valleys that once would been treacherous with woods and marshes, wolf and boar. At Ivinghoe Beacon in the Chiltern Hills, the second part of the track commences, the Icknield Way, a narrow corridor and ancient line of communication between South-West England and the East coast, a path worn steadily by traders, travelers, and invaders as far back as the Bronze Age.

On a night hike returning to his encampment in Latimer overlooking the River Chess, John Hargrave crossed the Icknield Way, inspiring the closing address of The Confession Of The Kibbo Kift, published in 1927, Hargrave’s public manifesto for a secret movement that was already seven years old.

Titled “The Spirit,” this song of the land draws upon William Blake’s capitalized allegorical forces (“Dimly they felt the threat of Just Men”) and James Joyce’s compound neologisms (“They hew out heaven-timber from the quickbeam of their own body-wit by the stave that runs in the blood.”) Add a heady pull on the Native American peace pipe, chased with a draught of the occult imaginings of theosophy, and you approach the style of “The Spirit.” As an evocation of English mysticism, a seeking of wordless wisdom on an ancient trail, it is the closest Hargrave’s writing came to the achievements of his modernist peers. Rolf Gardiner, an acolyte of D.H. Lawrence, briefly a member of the Kindred, was a critic of Hargrave but recognized the genius in “The Spirit,” describing it as “a truly magnificent exhortation, the authentic voice of the seer crying in the wilderness of stupid wayward men; it is the voice of the gods in the soil of Britain.”

“The Spirit” is a shamanic call to enter a state of wordless wisdom and silent communion with the undersong of the British soil. Hargrave knew yoga and meditation through his association with theosophy. He synthesized Eastern ideas — the clarity of unbeing — with the sensual being of Lawrence, that knowledge in the blood, “when the mind and the known world is drowned in darkness everything must go.” The night hike was a way into the deep knowledge buried beneath civilization. The charged, adrenalized sensation of being alone with nature, every sense alive to predators — this was being! This was life! No wonder scholar David Bradshaw has seen something of John Hargrave filling the red trousers of Mellors, Lady Chatterley’s Lover himself.

“The Spirit” closes with a call for the great men to go into isolation and prepare themselves for the work to come.

I shall go where the great trees stand, deep into the half-light of the woods whelming upon the giant bodies of the beech. I know the place where the afterglow shines like a pale halo upon the hill, and there the ash and the elm take hold upon the earth, flinging their strength into the sky. And over the summit of the hill on slanting ground a crab tree and a crooked thorn crouch and clutch each other.

I shall come around them uneasily and pass under the ash and the elm with an intaking of breath, and so down the valley to the track that runs into the pine wood where the darkness closes in, and the feet tread noiselessly, and the lungs are filled with the scent of the hanging curtains, the needled carpet and the cones…

Tread softly over the grass that springs out of the blood and bodies of old heroes of the Icknield Way long since gone to dust.

Back to the place of dwelling, to the encampment.

The land was where the Kindred overcame the servitude of their modern industrialized lives. The Kindred sought to tap into a strata in the cultural soil containing remnants of “Anglo-Saxon, Viking, Celt, and the Neolithic builders of barrow, dolmen, and the old straight track,” a “new and vital patriotism” aimed at overturning the capitalist and socialist alike. But the land was not an end in itself. Their educational policy, designed so that the child would recapitulate the primitive life outdoors, was “no mere sentimental Thoreauism or imitation Tolstoyan attitude towards life.” Hargrave was in earnest in working toward social change. This was not just a series of interruptive gestures. Pragmatic, if possessed of a wildly contradictory philosophy, the Kibbo Kift were training for leadership. Technology would liberate man from work, and afford the leisure required for a Kibbo elite to remake society. The prehistoric peoples of the land were just one of the sources this future could tap.

It is Hargrave’s early concern with regenerating national stock and his mystical conflation of blood and land that has lead some to describe him and his movement as fascistic. The Kindred were swimming in the same current of ideas as fascism. Blood and soil. Regeneration of the race. The movement’s later assault on the bankers and international finance — all hallmarks of the Nazis. James Webb argues in The Occult Establishment that not too much should be made about the crossover between fascism and the “illuminated movements” (his description of groups like the Kibbo Kift driving for spiritual development in the psychic ruins of the Great War) in the 1920s. While both the woodcraft-inspired movements and the German Wandervogel shared a “vicarious expectation of an idealistic revolution,” and Hargrave’s books in translation were a leading influence on the Bunde (a precursor to the Hitler Youth), the “only prominent member of the English illuminated group who joined a fascist party seems to have been the originator of the guild theory, A.J. Penty.”

The Kindred were intended to be a movement that transcended party politics, beyond the Bolshevism of the Russian Revolution (1917) and Mussolini’s Fascism (Il Duce came to power in 1922). By 1926, Hargrave and his followers were being demonized by Nesta Webster, a prominent conspiracy theorist whose work built on the notorious forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. She linked the Kibbo Kift with communists and socialists in a world-wide fraternity with the devil. Yet, despite the fact that their contemporary critics were fascists, the Kibbo Kift project shared some of its DNA with fascism, primarily its conviction that an elite cell of individuals could go amongst the people and guide them, syndicalist thinking that has no respect for democracy and majority rule.

The futurist energy of the movement distinguished it from the gentler longings of the Edwardian era. In an essay on the generations of the twentieth century, [HiLobrow.com’s] Joshua Glenn characterizes those born between 1884-93 (John Hargrave was born in the generational cusp year of ’94) as an international cohort outraged with the world they inherited:

The romantic anti-capitalism … of their elders wasn’t good enough for the Modernist Generation, who dismissed 19th-century utopianism as a quietist longing for a mythical — often neo-medieval — golden age. Instead of looking backward nostalgically (i.e., retrogressively), utopian Modernists discovered and invented what Van Wyck Brooks (born in ’86) called a “usable past.”

Ancient Britain was Hargrave’s “usable past” which he employed in his syndicalist approach to democracy. Unlike his romantic elders, he expressed the agency of mankind in pseudo-scientific terms. “The history of the human race is truly the history of ideas, and it would be possible to record the development of mankind as the work of a) individual idea-generators and b) group idea-carriers.” There is a biological metaphor at work here, in which the mass of men is infected by new ideas carried into their midst. More of a slow and evolutionary process than a revolution. (Revolutions smacked of Bolshevism.) Envisaging himself as an idea-generator and the Kindred as idea-carriers, he anticipates Richard Dawkins theory of memes, in which ideas propagate like genes using our minds as temporary hosts.

There is more science fiction within the Kibbo Kift project, from H.G. Wells’ presence on the advisory board to their outlandish costumes. Hargrave’s followed the Confessions of The Kibbo Kift with a science-fiction novel, The Imitation Man (1931), about a scientist who transposes the alchemic formulas of Paracelsus (an abiding interest of Hargrave’s and described in the novel as “the founder of the science of modern medicine, whose extraction of the ‘essential spirit’ of the poppy resulted in the production of laudanum”) into chemical formulas and succeeds in growing a homunculus in a glass jar. This is very Brave New World. In fact, Aldous Huxley’s brother, Julian, was also on the advisory board of the Kibbo Kift, emphasizing the progressive futuristic promise of the movement, albeit one bulwarked with its “usable past” of the collective unconscious seething under the English landscape. Huxley’s future dystopia, which included children grown in jars, was published the following year.

This is an extract from Matthew De Abaitua’s essay on the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift to be published in The Idler in 2010. De Abaitua’s debut novel The Red Men was shortlisted for the Arthur C. Clarke Award. He can be found at the website Harry Bravado.