Becoming Animal

By:

December 22, 2009

Reeling and writhing and fainting in coils formed the core curriculum at the seaside school in Wonderland. But it takes more than the necessities to navigate today’s media soup; we need conceptual art.

[John Tenniel, The Gryphon and Mock-Turtle, 1865]

Enter Gail Wight. In School of Evolution (1992), Wight took the fish to college. She updated the lesson plan for an advanced class of koi in the SF Art Institute pond, conducting an all-day seminar in ichthyology, aesthetics, and, finally, evolution, encouraging them to take the next step.

[School of Evolution, 1992]

Gail Wight is a multimedia conceptual artist who approaches the natural environment and the practice of science with a skeptic’s clarity, irreverent glial leaps, and deep empathy. Based in California, her work ranges across disciplines, continents, and species, to reveal very personal stories about how we are in the world, and who we’re here with.

[“Fighting Naturalist,” from Master and Commander, dir. Peter Weir, 2003]

It’s not so much that she talks to the animals as that she recognizes the value in meeting them half-way. In Rodentia Violoncello (2003) and Rodentia Chamber Music (2004), Wight switched roles from teacher to guidance counselor, showing lab mice how art is a more promising career path than science.

[Rodentia Chamber Music, 2004]

[Rodentia Violoncello, detail, 2003]

She built them a gated community full of desirable things: nooks and crannies, sawdust shavings, switches shaped like whiskers, mousefood, and other mice. The environment just happened to look exactly like a plexiglass cello (in Violoncello) or an early music ensemble (in Chamber Music). The mice like to swat at the whiskers, perhaps because they too have whiskers, or perhaps for other reasons of their own. At any rate, when they do, a short musical phrase is played, while motion-sensors placed here and there amplify their scurryings, creating ad hoc HiLo harmonies punctuated by Cageian pause.

[John Cage, 4’33”, composed 1952]

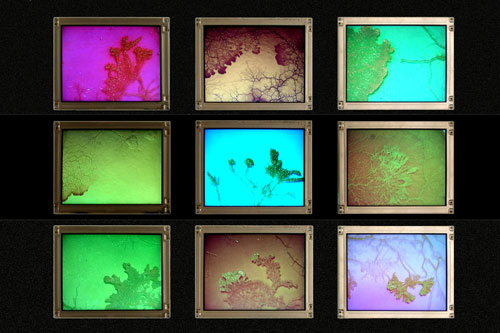

But something doesn’t need a pretty face to be a contender. In Creep (2004) Wight pays homage to the sublimity of slime. She tinted its agar using non-toxic dyes and videotaped its time-lapsed growth. Sometimes the slime (physarum polycephalum) would become the color of its food, or a more saturated version; sometimes, its complement. The resulting chroma ballet is a slow-motion Northern Lights, a puddled reflection of another sky.

[Creep, 2004]

[Creep, 3 views, 2004]

In many of these pieces Wight plays with time, and its scales. Often talking to the animals, or the plants, means slowing down to pick up on their patterns. Our lives and thoughts are a blur to a tree, for example; and are even more so to the ancient rock of the planet.

[Center of Gravity, 2008]

In Center of Gravity (2008), Wight displays prints of the glacial rorschachs of core samples from endangered environments, with the motion of visitors triggering low ululations of sound. “Who dares enter the tomb of the Earth?” To answer Igneous, we need to slow down enough to hear him, we need to enter into his time as well as his tomb.

[J’ai des papillons noirs tous les jours, 2006, fabric, HO lights, pins]

But at no point does she deny our own animal nature: “the laughing animal, the weeping animal,” as Nietzsche aphorized. For all that we cannot hear and do not know, we often know too much. The French have a phrase for it, “j’ai des papillons noirs tous les jours.” In Wight’s piece of the same name (2006), the papillons noirs of depression are pinned right through their faux little hearts, while what’s left of their electric souls blinks slowly away like the receding stars in the sky.

[The Anatomy Lecture of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, Rembrandt, 1632]

[An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, Joseph Wright of Derby, 1768]

In All My Leucotomes (2006) she turns to history painting. Following in the brushtrokes of Rembrandt and Joseph Wright of Derby, Wight created a large-scale group portrait of all the butter knives in her house. The members of the group so honored? Lobotomy recipients. The leucotome (the instrument used to lobotomize) was pretty much a butter knife: right up through the eye socket, wiggle it around, and presto! No more crazy. Could practically do it at home; the developer and popularizer of the procedure, Walter Freeman, actually roadtripped all over the country on house calls.

[All My Leucotomes, 2006]

Of course it didn’t work as expected, except that whatever else a lobotomy was, it was irreversible. Our love of control and technology overwhelms what should be its real object, and under the guise of improvement or experimentation, we kill the things we love. Ask not for whom the dove cries, it cries for thee.

[When Doves Cry, Prince, 1984]

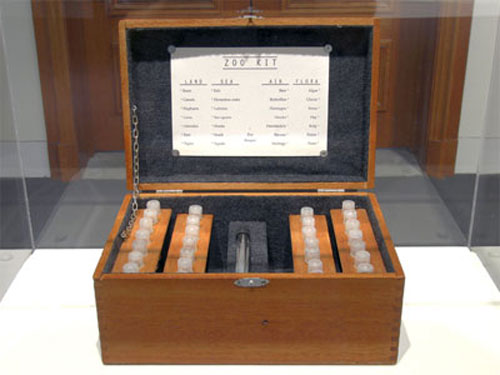

Still, somebody has to run the asylum, and in Zoo Kit (1997) Wight provides us some likely candidates. Collaging together the visual language of Victorian science with the conceptual stance of Fluxus, she assembled a DIY kit for a zoo. Inside a velvet-lined, hinged wooden box are rows of test tubes labeled in script, containing DNA samples. Fauna on one side, flora on the other. And in the middle sits a single tube: the zookeeper. Us.

[Zoo Kit, 1997]

“The obsession to make art is a neurological disease” – Gail Wight

Gail Wight is Professor in Experimental Media Arts at Stanford University, and can be reached via her website: http://www.stanford.edu/~gailw/

Artists in residence archive.