Whence Middlebrow?

By:

October 21, 2009

Here at HILOBROW, we agree with Bourdieu that aesthetics and lifestyle choices aren’t entirely independent of social class. Though (along with Carl Wilson) we reject the reductionism of his Distinction, we do rely on Bourdieu’s notion of the “disposition” (a tendency to act in a specified way, to take on a certain position in any field) and the “habitus” (the choice of positions in a field, according to one’s disposition).

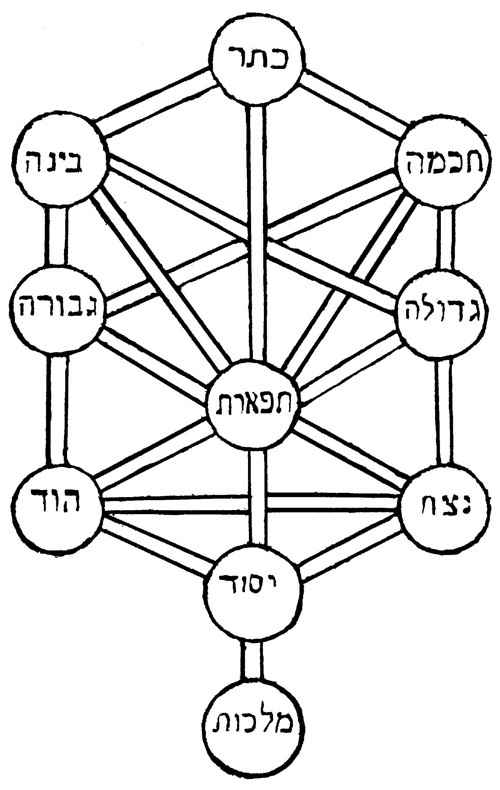

We’ve named and located 10 bourdieuian dispositions — 4 heimlich (Highbrow, Lowbrow, Neo-Aristocratic (Anti-Lowbrow), Quasi-Populist (Anti-Highbrow)); 2 gemütlich (High Middlebrow, or what Dwight Macdonald called Midcult; and Low Middlebrow, which Macdonald, following Adorno, called Masscult); 2 unheimlich (Nobrow, not to be confused with John Seabrook’s confused use of the term; and HiLobrow, our own coinage); and then there’s Unbrow, which Van Wyck Brooks confusingly called Lowbrow. There are various habituses possible within each of these dispositions, but since the mid-17th-century, these dispositions have formed into an invisible matrix of influence.

[This is a version of comment that I posted, earlier this morning, to John Holbo’s recent post at Crooked Timber about Russell Lynes, Virginia Woolf, and Carl Wilson. Holbo is brilliant, but — like Wilson, whom we also consider a friend — he seems to be pro-Lynes and anti-Woolf, whereas HiLobrow.com is anti-Lynes and pro-Woolf. Too bad! But perhaps we can change their minds.]

Our hypothesis is that the 4 heimlich dispositions formed in the mid-17th century and after because of Spinoza and the so-called Radical Enlightenment. Before that time, Highbrow and Lowbrow were united, e.g., in a figure like Shakespeare. For two centuries after this Shevirat HaKeilim-like moment of shattering, Highbrow and Lowbrow remained fond of one another, copacetic and complementary; but as recounted by historians like Lawrence W. Levine, in the late 19th century a wedge was driven between High and Low. Virginia Woolf’s essay is a lament about this suddenly widening gap; unlike those intellectuals of her time who celebrated Middlebrow for bridging High and Low, she blamed Middlebrow for the divide. Writing a decade earlier than Woolf, Van Wyck Brooks also deplored what was happening to Highbrow as it lost contact with Lowbrow. However, Brooks made two major errors: he confused Lowbrow with Unbrow (philistinism), and he called for Middlebrow to close the divide.

Whence Middlebrow, the uncanniest of guests? We’re still trying to track it down — we’re pretty sure it existed before it was named in the Twenties. It might have been born in the very late 19th or very early 20th century, per Woolf and Brooks. I think Christopher Lasch is likely analyzing the disposition High Middlebrow — though he mostly isn’t discussing taste — in his The New Radicalism in America, 1889-1963. But in “Masscult & Midcult,” Dwight Macdonald blames Low Middlebrow on the industrial revolution, and traces its origins back to mid-18th-century England.

At HiLobrow.com we’re interested in tracking Middlebrow’s origins, but the critical thing is our discovery of its true role and position within the matrix of modern dispositions: Middlebrow does not mediate between Highbrow and Lowbrow; and therefore it should not be championed by those who are attempting to champion social mobility (i.e., from lower to upper class) in the sphere of culture. Lynes was misguided in this effort — and, as previously mentioned, so are Andrew Ross, Susan Jacoby, A.O. Scott, the author of a recent Chronicle of Higher Ed essay titled “Confessions of a Middlebrow Professor,” and even our friends Alex Beam (author of a recent history of the Great Books series) and Carl Wilson. Despite what sounds — to our ears — like her snobbery, Woolf was dead-on when she claimed that Middlebrow was only making it more difficult for Highbrow and Lowbrow to reunite; and Macdonald and Adorno (also branded as mandarins) were also correct about this.

Where does Middlebrow sit on the matrix of modern dispositions — and where do all these other “brows” that I’ve named sit? We’ve got it mapped out, and we’re revealing the answer slowly, whenever we get a spare moment (because we have day jobs) right here, on this website.

PS: HiLobrow may not actually be a disposition that anyone can actually inhabit; it might be more of an ideal — Highbrow and Lowbrow, reunited and it feels so good — that can only be articulated negatively, by saying what it isn’t. “Let me admit frankly that I have not in my experience encountered any certain specimen of this type; but I do not refuse to admit that as far as I know, every other person may be such a specimen. At the same time I will say that I have searched vainly for years….”

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).