Winds of Magic (3): Oral or Anal?

By:

September 27, 2009

The first thing to be said about the concept of the “oral history,” as it applies to rock biography, is that Sigmund Freud — damn him! — has triumphed again. For what purer display of Freudian oral fixation could there be than that provided by an assemblage of gobby, gossipy, wilful, indulged and pleasure-craving musicians all spewing off into the mike of some gratefully enabling recorder? American Hardcore: A Tribal History, Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History Of Punk, We Got The Neutron Bomb: The Untold Story Of LA Punk — the din of colliding ego-trips rises from all these books. The second thing to be said is that the oral history is a sign of the times; a racy, trashy, sub-artistic form, in which the author has become a producer — marshaling his oodles of raw content, generating his pseudo-narratives in the editing suite — and the book has become, not a text, but a spectacle: reality TV, if you like, for rock fans who can read.

The current maestro of rock’n’roll oral is the transplanted Scotsman Brendan Mullen, who with Whores: An Oral Biography of Perry Farrell and Jane’s Addiction is making his third contribution to the genre. (The first two were Lexicon Devil, a history of the Germs, and We Got The Neutron Bomb.) Whores is highly entertaining, basely fascinating and — almost despite itself — rather informative. Mullen, founder of famous LA punk rock hole the Masque and seasoned hipster, clearly knows how to talk to musicians — both the rockstars and the fuming failures — and he gets the good stuff out of them. Unguardedly, his subjects preen and bitch and justify. They tell their stories. Crack pipes, blowjobs, see-through unitards, it’s all here; the eldritch light of decadence plays gleefully across the pages of Whores. But there’s also a surprising amount of insight on offer. The music of Jane’s Addiction, for example, stands freshly revealed to us when we learn the details of the band’s formation; how Eric Avery came up with those elementally brooding bass lines all by himself, in a garage; how drummer Stephen Perkins and guitarist Dave Navarro were plucked, enormous-haired, from a high school heavy metal act called Dizastre; and how Perry Farrell, ten years older than his bandmates, was a fashion mutant besotted with English Gothdom — Bauhaus, Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Cure. Put it all together, pour on the drugs, and what do you get? A creepy shamanistic rumble, shot through with metal licks, underpinned by a majestically lonely bass: Jane’s Addiction!

No amount of background, of course, could explain the effect of Perry Farrell’s voice, that sound piped down from halls of celestial orgy, that thin, witchy tone singing about oceans and mountains and three-way sex. The information that his dad was a groovy jeweler named Al Bernstein who spent the ’70s “walking around Miami Beach… with a Fila headband and a bikini bathing suit with gold around his neck” seems helpful, as do Farrell’s accounts of his own fashion experiments (“I was in a Paisley Underground band for about a minute. I got a Paisley shirt and I combed my hair down into bangs, and then I thought, ‘Shit, this is pretty shortsighted.'”) But Farrell is ingredient x, the point at which biography falls down….

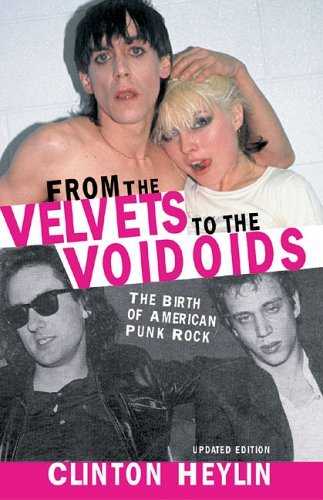

In the opposite corner, as it were, from Mullen and his method stands Clinton Heylin, whose From The Velvets To The Voidoids: The Birth Of American Punk Rock (Chicago Review Press), originally published in 1993 but now making the rounds in an updated edition, is very much NOT oral history. From The Velvets may include great fat chunks of direct-speech testimony from Lou Reed, Richard Hell, and so on, but the voice of the Author — the mighty, synthesizing intelligence that has brought it all together — is supreme. “Like other forms of ‘art’, high and low, the history of popular music contains its fair share of fractures…” drones the opening sentence. From The Velvets makes quite a to-do of its own thoughtfulness, its own grasp of nuance; every second paragraph begins “If…,” “Yet…,” “Although…,” “Despite…,” or “However…,” as Heylin pirouettes sweatily between idea and counter-idea. And in a lengthy “Postlude” to the new edition he puts on a pedagogic frown and takes the oral historians to task for their various cop-outs and improprieties.

In particular, and for obvious reasons, Heylin is dissatisfied with Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain for 1997’s Please Kill Me. I was once taught Latin by a withered old man whose delight it was to punish classroom misbehavior by bringing down an enormous dictionary on the head of the offender; this, more or less, is Heylin’s tactic as he lays into Please Kill Me. “The lack of any authorial introduction…” he writes, “[or] bibliography of debt or discography of sounds — nope, not even an index — makes this a true exemplar of postmodern nonfiction — small-h history, and sod the context. Adrift in an ocean of opinions, the reader must decide what to believe from the whole jumble of lies and damned lies. No qualifying phrases here, no messy historical inter-relationships, just one misunderstood maverick after another…”

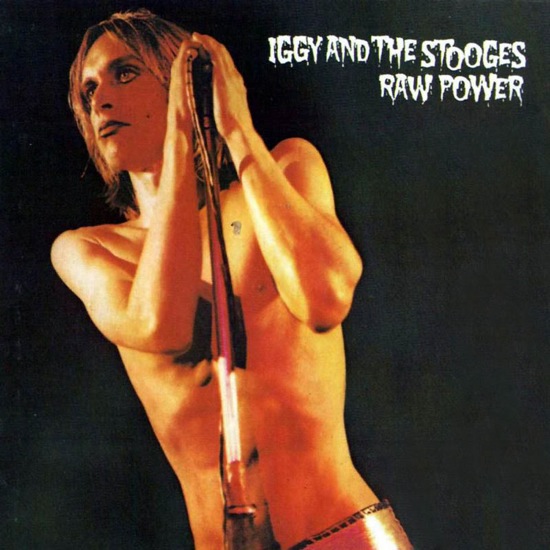

Heylin is obviously right about most of this; the oral history tends to lack context; sloppiness and subjectivity abound; the afflicted ramblings of some muso are no substitute for the facts, etc. “In my original interviews,” he writes, “I was frequently obliged to correct musicians in mid-interview, lest the order of things become inverted.” (How they must have loved that!) The problem is that big-H History, even when written by one so stringent as Clinton Heylin, is just as unreliable, just as susceptible to ego-driven error. Getting the facts straight, filling in the background, knitting your theorems together, you can still miss the story completely. Here’s Heylin, for example, on late-period Stooges: “They unwisely reassembled in London in the summer of 1972, after David Bowie offered to produce an Iggy Pop album. They continued to produce music of stark primitivism but recorded only one more studio album, the disappointingly restrained (indeed ill-named) Raw Power, which suggested that Bowie’s main forte was sanitizing genuine innovators for public consumption, particularly when taken in association with the results he achieved on Lou Reed’s Transformer.

This, I think, turning back to our Freud, we can justly call “anal” history — that is, history in which all the facts, whatever their shape, are squeezed through a single, jealously pinched aperture of authorial perspective. The signature style is one of mincing and incessant judgment; what a shame that the Stooges were deprived of the benefit of Mr Heylin’s counsel in 1972, when they “unwisely reassembled.” Heylin gets it wrong about Raw Power — an album which a three-year-old could tell you is not “restrained” — because he is too busy making his case against David Bowie. Committed to this argument, to this display of analytical muscle, he is led to his final loony act of equivalence, in which the gay chamber rock of Transformer, tart and bejeweled, is given the same sonic value as the shrieking, bacon-fat-on-the-tape-reel high end barrage of Raw Power. (If it proves anything, the fact that David Bowie worked on these two records within months of each other proves that he is a solid-gold GENIUS.)

Which, then, is to be preferred? The weightlessness of the oral history, with its fluff and noise and trivialities, or the gravity of the critical work, with its tendency to land heavily in the wrong place? As my shrink used to say, “I think what we’re looking for here is a balance.” Clinton Heylin has undoubtedly performed a historical service with his monastic dedication to “the order of things,” just as Brendan Mullen, juggling his quotes, has fluked his way to certain fugitive truths; the awful fate of Alternative Rock, for example, is presaged in the final pages of Whores when Dave Navarro’s cousin burblingly recounts how Dave first met Carmen Electra. “There’s a call on his cell phone and he’s like, ‘Dude, it’s a fucking friend of Carmen’s right now and they’re all together and they want me to come down and meet her. Should I go?'” Go, Dave Navarro, go, and take our childish dreams with you.

Originally published by the Boston Phoenix, July 2005. From 2004-08, our friend and colleague James Parker, currently a contributing editor at The Atlantic, was a culture critic for the Boston Globe’s Ideas section and for Boston’s alt-weekly, The Phoenix. HiLobrow.com has curated a collection of Parker’s writings from this period. This installment is the third in a series of ten.