Winds of Magic (2): The Real Peter Pan

By:

September 20, 2009

On January 16, 2004, outside the California courthouse where he had just been arraigned on seven counts of child molestation and two counts of administering an “intoxicating agent with intent to commit a felony,” Michael Jackson climbed up onto the roof of his SUV and struck a pose.

It wasn’t a pop pose — one of his freeze-framed, blast-lit snarls or crotch-grabs. Nor was it a pose from his life as a global celebrity — the veiled figure waving faintly from limousines, balconies, and departing ambulances. This pose was strange and statue-like, addressing itself apparently to history, or to memory: the chin was raised, the right arm lifted high, the open right hand extended in a gesture that mingled defiant self-acclamation with a commanding, beckoning wave. Had anyone outside the courthouse ever passed an afternoon in London’s Kensington Gardens, and stood before a certain bronze figure by Sir George Frampton, the pose, in all its boyish sternness, would have been familiar. At this most ruinous moment in his life, Michael Jackson was once again invoking the dazzling, unshamable spirit of Peter Pan.

Michael and Peter go way back. The Peter Pan theme has been woven, with what in retrospect looks like considerable care and calculation, into the fabric of the Jackson image. His oft-reported dreams of flying, the wispy infantilism in interviews, his famous “stolen childhood,” the endless talk of the “magic” of children, and of course Neverland, his 2,700-acre ranch near Santa Barbara with its carousels and private zoo — in the context of his current difficulties, these items make up what might be called his aesthetic alibi.

In his 1991 biography Michael Jackson: The Magic and The Madness, J. Randy Taraborrelli reports a conversation that took place in the early ’80s between Jackson and Jane Fonda. The two stars were discussing “what kind of film property would be best for Michael” when Fonda suggested Peter Pan, a project that both Steven Spielberg and Francis Ford Coppola were then considering.

“Tears,” writes Taraborrelli, “began to well in Michael’s eyes. He wanted to know why she suggested that character. She told him that, in her mind’s eye, he really was Peter Pan, the symbol of youth, joy, and freedom. Michael started to cry. ‘You know, all over the walls of my room are pictures of Peter Pan. I totally identify with Peter Pan,’ he said, wiping his eyes, ‘the lost boy of Never-Never Land.'”

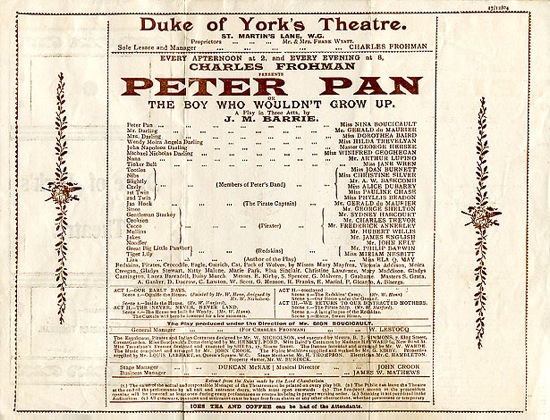

Myths have their own life, and the younger the myth the more trouble it can get into. Peter Pan is only a hundred years old. When the curtain came down on the first performance of Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up at the Duke of York’s Theatre on December 27, 1904, the mostly adult audience went wild. Within days the play was a Star Wars-like sensation and Peter, played with blazing puerility by Nina Boucicault, had entered the permanent cosmology of childhood. He was sharp, daring, vicious, unstoppably creative. That Michael Jackson’s simpering redaction represents a considerable distortion of the original is beside the point. In his weirdness and calculation the King of Pop may have reached deeper inside the myth than anyone else would care to, because the truth is that the same tensions and troubles that attend Peter’s latest appearance, on the roof of Jackson’s SUV, were present at his birth.

J.M. Barrie, the tiny and solemn-eyed Scotsman who wrote the play, was quite as complex and arresting a figure as Michael Jackson. Born in 1860, Barrie was a household name by the time he reached his mid-30s; his distinctively forked literary style, sharp but whimsical, pithy yet somehow nostalgic, was developed through early efforts in journalism and then put to hugely commercial use in a string of plays and novels. Like Jackson he was slight, boyish, soft-spoken, unhappy. Like Jackson, too, he was childless — his marriage, which ended in divorce, appears to have been unconsummated — and he gravitated toward other people’s children, particularly boys. Genius, he once wrote, “is the ability to be a boy again at will.”

Walking his enormous dog Porthos through Kensington Gardens in the 1890s, Barrie met and befriended a bright and forward 4-year-old named George Llewelyn Davies, who was there with his younger brother Jack and their nanny. George was wearing a red tam-o’-shanter; for Barrie, it was love at first sight.

Barrie, Porthos, and the boys would meet regularly, and the spontaneous, compulsive, extraordinary fabulating began. Later he would stew up his feelings in a 1902 novel titled The Little White Bird, in which George becomes “David,” Barrie becomes “Captain W” (a childless writer), but Porthos, with a St. Bernard’s faithfulness, remains Porthos. David, wrote Barrie, “strikes a hundred gallant poses in a day, and when he tumbles, which is often, he comes to the ground like a Greek God.”

It was as nothing for Barrie to install himself in the boys’ affections; his child-friends were numerous, and by now he had quite an arsenal of seduction. There was his ear-wriggling and what he called his “famous manipulation of the eyebrows,” one going up and one going down “like two buckets in a well.” There was also his habit of silence, the mysterious brooding pauses that so disconcerted adults but which children apparently found quite companionable. And above all there was his huge instinct for make-believe.

George and Jack, and later their brothers Peter, Michael, and Nico, became delightedly embroiled in Barrie’s ghost-world, a parallel-universe Kensington Gardens in which babies flew from their prams like birds and children who stayed in the Gardens after lockup were buried by an eager, ambiguous sprite named Peter Pan, always “ready with his spade.” By the time he finally met the boys’ parents, the glamourous Sylvia and Arthur Llewelyn Davies, at a high-society dinner party, Barrie was part of the family’s dreamlife: They had no choice but to accept him. Soon he was a regular at their house at 31 Kensington Park Gardens.

And the closer he drew to the boys, the higher his own imaginative temperature ran, as in this passage from The Little White Bird:

“Why, David,” said I, sitting up, “do you want to come into my bed?”

“Mother said I wasn’t to want it unless you wanted it first,” he squeaked.

“It is what I have been wanting the whole time”, said I, and then without more ado the little white figure rose and flung itself at me. For the rest of the night he lay on me and across me, and sometimes his feet were at the bottom of the bed and sometimes on the pillow, but he always retained possession of my finger, and occasionally he woke me to say that he was sleeping with me. I had not a good night. I lay thinking.

Barrie wrote wittily, on occasion satirically, but also straight from the roots of his brain, in floods of untempered fantasy. The Little White Bird was a smash hit in its day, a sentimental triumph whose success had the unlooked-for effect of driving Barrie from Kensington Gardens, so avidly was he pursued there by mothers who had read the book. But today the novel has a murky, somnambulist feel, as if its author were grappling unsuccessfully with an enthrallment, a bad dream, something to which he cannot find the key. The formula, as it were, still eluded him.

A post-Freudian age would come to regard Victorian spellbinders like Barrie and Lewis Carroll through narrowed eyes; surely this overheated attentiveness to children could not be without taint. And indeed the image of Carroll, obsessed photographer of little girls, writing to the mother of a potential subject to enquire “what is the minimum amount of dress in which you are willing to have her taken” is hard to shake.

Was Barrie a pedophile? Nico Llewelyn Davies, youngest of the boys, swore in his old age to a biographer that he had “never heard one word or saw one glimmer of anything approaching homosexuality or pedophilia: Had he had either of these leanings in however slight a symptom I would have been aware.” Whatever the sexual component may have been in Barrie’s lifelong attachment to the boys, and whatever its strength, he never acted on it. Instead, with a celibate’s tremendous energy and the half-conscious cunning of the artist, he displaced it.

Peter Pan had already appeared in The Little White Bird, as part of a story told to “David,” but after an ecstatic pirate-and-redskin-filled summer holiday with the Llewelyn Davies boys Barrie began work on a play with Peter as the central character. The sublimation was total, and totally purifying. The hard, golden, irreducible figure of Peter Pan — “gay and heartless,” waving his dagger and tooting idly on his pipes, gnashing the “little pearls” of his baby teeth and bellowing orders in his “captain voice” — is the quintessence of Barrie’s child-centered dreaming. Peter’s cruelty counters the ooze of Barrie’s sentimentality, his selfishness punctures Barrie’s whimsy. He is not a symptom. He is the cure.

Michael Jackson, quite obviously, is not Peter Pan, nor is he J.M. Barrie. The fact that Jackson named his home, now perhaps a crime scene, after Peter’s island of fantasy-fulfilment produces ironies almost too barbarous to comment upon. Outside, the gilded lawns and the gambolling chimps; inside, the private room in its force-field of surveillance, guarded by floor-to-ceiling electric eyes, where Jackson conducts his “sleepovers.” Barrie would never have whispered to a TV interviewer that “children are the face of God”: He knew children too well for that. Barrie even proclaimed himself disappointed with the Kensington Gardens statue — which he had commissioned and paid for — because it failed to “show the Devil in Peter.”

But Barrie in his wildest flights could not have conceived of Michael Jackson — the black man whose skin turned white, the zillionaire changeling, the demonically powerful dancer, the alleged child molester who in 1993 performed at the Super Bowl halftime show, watched by over 120 million people, surrounded by 3,000 children singing “Heal The World.” His rise was phenomenal, unbelievable. Guilty or not, his fall will be Luciferian.

Originally published by the Boston Globe, July 2005. From 2004-08, our friend and colleague James Parker, currently a contributing editor at The Atlantic, was a culture critic for the Boston Globe’s Ideas section and for Boston’s alt-weekly, The Phoenix. HiLobrow.com has curated a collection of Parker’s writings from this period. This installment is the second in a series of ten.

MORE FANTASY ON HILOBROW: CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series | 65 Fantasy Adventures | Mervyn Peake | Lord Dunsany | H.P. Lovecraft | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Ursula K. LeGuin | Michael Moorcock | Gary Gygax | Clark Ashton Smith | Frank Frazetta | George MacDonald | John Bellairs | T.H. White | Wilkie Collins | M.R. James | Edgar Allan Poe | Lewis Carroll | Mikhail Bulgakov | Guy Endore | Alasdair Gray | Maurice Sendak | Tove Jansson | L. Frank Baum | Roald Dahl | Abraham Merritt | August Derleth | William Hope Hodgson | Madeleine L’Engle