Only Connect

By:

September 16, 2009

Last week the New York Times’s occasional “Op-Art” column was furnished by Inga Dubay and Barbara Getty, whose handwriting manuals explain and promote the italic hand. In “Write Stuff,” they offer italic as a balm to soothe the nation’s frayed nerves.

The country’s in a bad way, Dubay and Getty note. And it shows in our penmanship. The problem, they argue, is rooted in the grammar-school handwriting program known as the Palmer Method, “an ornate style that was difficult to learn and broke down under pressure.” They promise that we can “learn how to stop mumbling on the page” by “embrac(ing) letterforms born in the Italian Renaissance.”

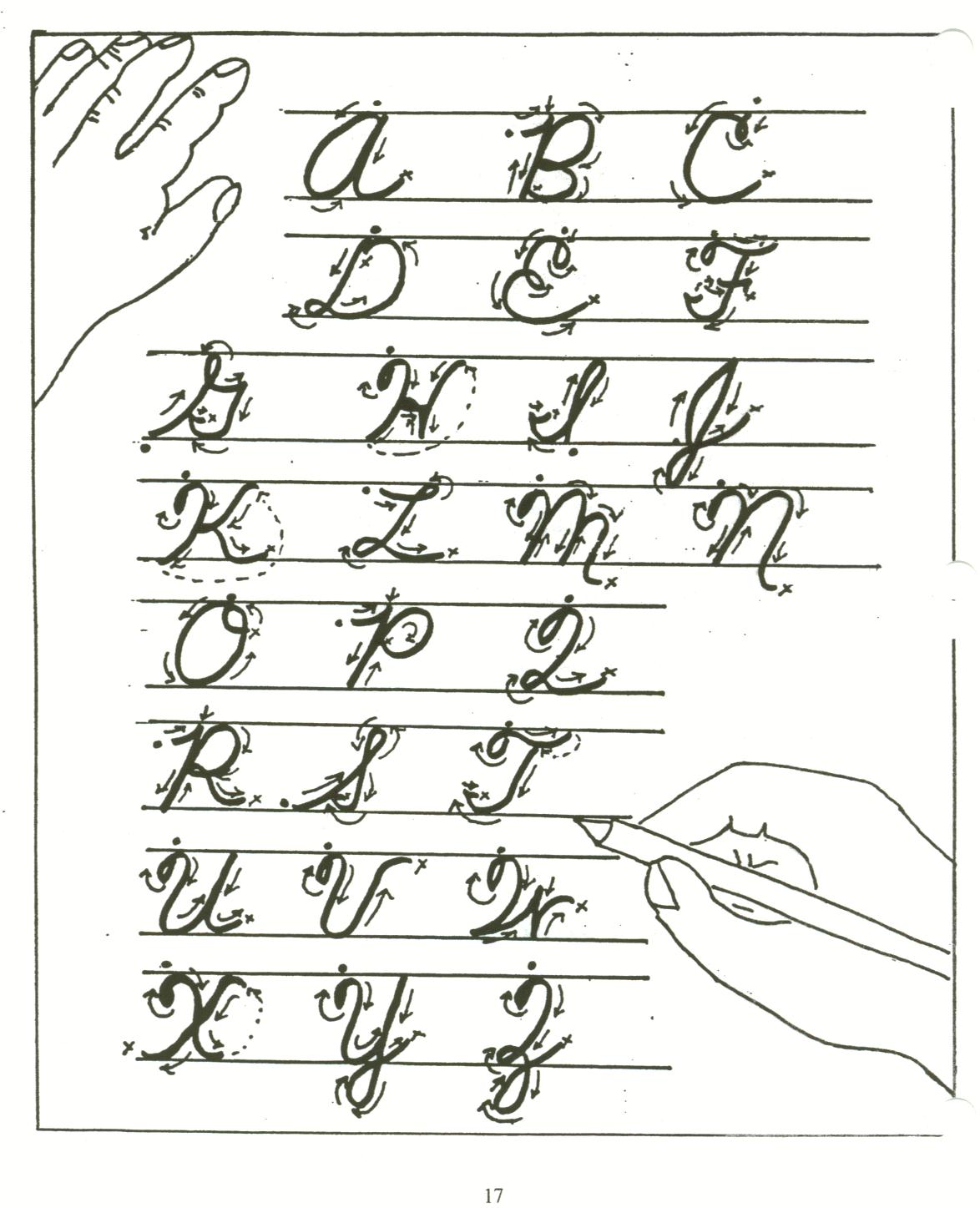

Dubay and Getty proceed with a quick primer on the Italic hand, with diagrams (on which you can practice your own italic letters in the print edition of the Times — score one for the physical newspaper!). In their instructions, they exhort us to relax: “letters do not have to be relentlessly connected,” they caution. “Many find this to be a relief.” And there’s something very twenty-first century in their injunction to avoid the death grip when holding one’s pen. Relax: everything depends on it!

As a bit of a loose joiner myself, I’m inclined to shape my line to their advice. But the middlebrow notion that correctness in penmanship breeds moral rectitude and economic vitality is as old as it is useless — it’s precisely what motivated the nasty Palmer-promoters of old. And as anyone who works with archival materials knows, the present has no monopoly on illegibility. In the literary sphere — where scribes might be inclined to fret over legibility —Boswell, Emerson, and Emily Dickinson all had blindingly crabbed hands.

Handwriting breaks down under pressure because we break down under pressure. And we always have — whether wielding reed, quill, or fountain pen.