Winds of Magic (1): Dark Chocolate

By:

September 13, 2009

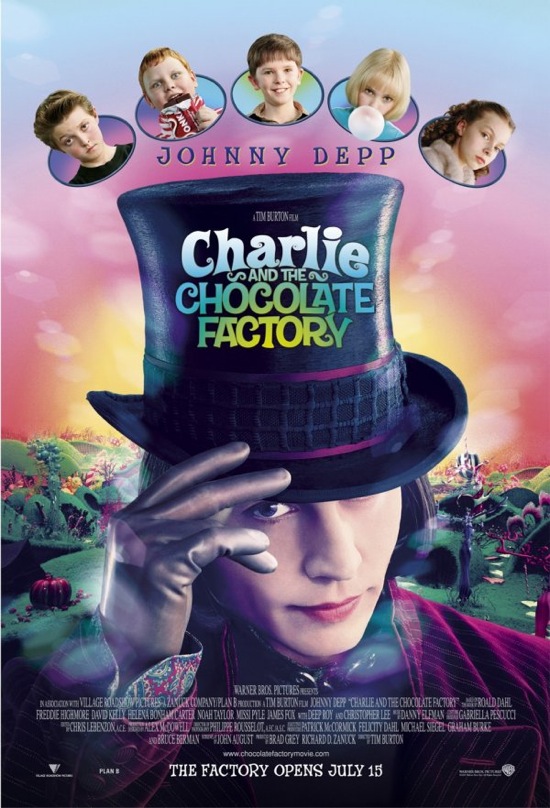

Director Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has many fine qualities, but they founder and die away to nothing on the eerie smoothness of his leading man’s chin.

Johnny Depp may be beautiful, but a Willy Wonka without his beard is no Willy Wonka at all.

And beardlessness is not the worst of it. In place of the compact and exclamatory figure of Roald Dahl’s 1964 book we have, in Depp, a Wonka who is green-faced, addled, epicene, who needs cue-cards to remind him what to say. Critics have noted his resemblance to Michael Jackson — this Wonka is damaged. Burton has invented a past for him: a horrid dentist father, a chocolate-hater who imprisons his son’s head in an orthodontic cage. Nice idea, but a fatal indulgence — the real Wonka has no past. He does not come hauling his problems, with a weak Jacksonian smile, but springs anarchically from nowhere, baggageless and fully formed, the little black fuse of his beard touching off the face that is ”alight with fun and laughter.”

It is this sharp-bearded, puff-of-smoke quality that announces Wonka as a fairy — a Puck, an imp, a Robin Goodfellow — and Dahl’s Chocolate Factory as a fairy tale, whose figures are not driven by some screenwriter’s conceit of character, but by their nature.

The tale, of course, is that of young Charlie Bucket, humble and deserving but condemned to eat cabbage soup with his shivering family in a shack on the fringe of some nameless industrial hub, until he finds the last of five Golden Tickets issued by Mr. Willy Wonka, mysterious candy tycoon, and in the company of four other children — who happen to be very poorly behaved — and their guardians, is granted access to Wonka’s incredible Chocolate Factory. There, the bad children are picked off one by one, each suffering a fate appropriate to his or her particular vice (greed, TV addiction, etc.), until only pale Charlie is left, at which point he is clasped to the Wonka bosom and pronounced the Factory’s heir apparent.

Some traditional fairy tale trappings are present. We have the buried ”Cinderella” theme, as Charlie is raised from poverty by the essential nobility of his nature (and the intercession of a fairy); we have the use of the powerful number 3 (three bears, three little pigs, three Wonka chocolate bars before the Golden Ticket is found); we have the violated interdictions — ”’Whatever you do, don’t go into the Nut Room!”‘ — and the appalling consequences. But the biggest clue to the book’s fairy nature is its abrupt and supernaturally enhanced cruelty.

When the Grimm brothers, Jacob and Wilhelm, were gathering and redacting Black Forest folk tales for their collections, they were careful to prune them of their sexual edge — Rapunzel, for example, ceased to be pregnant. But the violence was left intact: Cinderella’s stepsisters have their eyes pecked out by doves, Rumpelstiltskin rips himself in half, Little Brother in “The Juniper Tree” is decapitated by his stepmother and served to his father in a stew. ”Children,” wrote G.K. Chesterton, ”are innocent and love justice, while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy.” The Dahl Doctrine was to the point: ”Beastly people must be punished.” And beastly children above all. In Chocolate Factory, the parents who spoil them get away with bruises or a light coating of trash — it is the children who are stretched, inflated, distorted, jammed in pipes.

Here, Dahl was almost magically fortunate in his choice of illustrator. Quentin Blake’s gaseous, squiffy drawings, all pointy limbs and fried-egg eyes, act as pressure-valves for the story: whenever the action gets too nasty, the tension is flared off in a hi-speed illustration. Real suffering, in a Blake drawing, is impossible. The eye of a more somber and laborious draughtsman — Mervyn Peake, say, author/illustrator of the Gormenghast trilogy — would have turned the Factory into a torture chamber.

Unlike the great Victorian/ Edwardian enchanters, those dreaming bachelors and slightly worrying uncle-figures, Dahl (who died in 1990) was not child-besotted. Neither idealizing nor eroticizing nor even particularly respecting children — they are “much more vulgar than grown-ups,” he told an interviewer in 1986. “They have a coarser sense of humor. They are basically more cruel” — he came, we may say, from an older and harder tradition.

Writing for children was not his first thought. In 1959, as he began work on James and the Giant Peach, he was already well-established as a producer of macabre and highly adult short stories for The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, and Playboy. He was a thrusting, worldly character, well-dented by life. Born in Wales (in 1916) to Norwegian emigrants, he was speedily sent away to boarding school — which he loathed, and where he was regularly beaten. As a fighter pilot in World War II, serving in Africa, he was almost killed by a forced landing in the desert: His nose was driven into his skull, and his eyes were swollen shut for six weeks. By the time Charlie and The Chocolate Factory was published, Dahl had also endured the death of his first child, Olivia, from measles, and the serious injury of his infant son, Theo, in a road accident.

In Dahl’s writing there is no whimsy, and little nonsense. His style is craggy and telegraphic; in prose he admired not Kenneth Grahame but Ernest Hemingway. The deficits in his ability, as well as something of his vulgarity, are apparent in his attempts at verse. The songs of the Oompa-Loompas in Chocolate Factory, cautionary verses in the tradition of “Struwwelpeter” and Hilaire Belloc, have neither the crude energy of the former nor the wit of the latter. The thumping, merciless iambic tetrameter is — in Dahl’s hands — practically inert: “‘So please believe us when we say/That chewing gum will never pay….'” But doggerel, too, is the language of the fairy tale. (“Fee fi fo fum…”)

In our age of interpretation, fairy tales — as befits their magical nature — have suffered many fates. But they have survived them all, because they are obstinate, irreducible productions of psychic life. A Freudian like Bruno Bettelheim might be interested in the excremental torrent of Willy Wonka’s chocolate river; the woollier Jungian folklorist Robert Bly might address himself to Charlie’s lack of a strong father. And both would be right, in their way, without remotely affecting the essentials of the story. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has outlived accusations of racism (by the critic Lois Kalb Bouchard, after which Dahl rethought and eventually rewrote the Oompa-Loompas) and sadism (by the children’s author Eleanor Cameron, who now passes into history in the role of Dahl’s priggish accuser).

The Chocolate Factory, like Jack’s beanstalk and the gingerbread house in “Hansel and Gretel,” sits with a sort of enlarged, insolent brightness in the territory of the unconscious. “‘Notice how all these passages are sloping downwards!’ called Mr Wonka. ‘We are now going underground! All the most important rooms in my factory are deep down below the surface!'” Way down beneath the Factory lies, miraculously, a toy-town Xanadu, a version — entirely in candy — of Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” underworld. Through caverns measureless to man the chocolate river rolls. There is the same sense of huge forces at war — the rushing-down of the chocolate waterfall, the hydraulic upward heave of the pipes, with their “never-ending suck-suck-sucking” — and of a primal abundance of energy: “‘Thousands of gallons an hour, my dear children! Thousands and thousands of gallons!'”

The ups are fierce, the downs are fierce. Extremes of feeling are the currency of fairy tales, and Dahl pursued them. In his first novel, 1948’s Some Time Never, the pilot-hero is overcome by a sickness that “seemed to concentrate in one small fiery pin-point just below the ribs, a long, thin, white-hot needle pressing deeper, deeper through the flesh, into the empty coldness of the stomach then up toward the heart; and when the sharp, hot point touched the outer tissues of the heart it was like all the mental pain of the world pouring in hot rivulets through your body and dripping drop by drop from out your fingertips….”

Sixteen years later, when Grandpa Joe is first shown Charlie’s Golden Ticket, this awful inward pressure is reversed, and from that same single laser-spot of sensitivity the energies expand outward in a shockwave of joy: “…Very slowly, with a slow and marvelous grin spreading all over his face, Grandpa Joe lifted his head and looked straight at Charlie. The color was rushing to his cheeks, and his eyes were wide open, shining with joy, and in the center of each eye, right in the very center, in the black pupil, a little spark of wild excitement was slowly dancing.”

The white-hot needle’s tip, the dancing spark: This is the eye of existence, where children live. Around this point the extremities are always in motion: good and evil, hope and terror, reward and punishment. And if — like Roald Dahl — you can put your finger on it, you are a teller of the oldest tales.

Originally published by the Boston Globe, July 2005. From 2004-08, our friend and colleague James Parker, currently a contributing editor at The Atlantic, was a culture critic for the Boston Globe’s Ideas section and for Boston’s alt-weekly, The Phoenix. HiLobrow.com has curated a collection of Parker’s writings from this period. This installment is the first in a series of ten.

MORE FANTASY ON HILOBROW: CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series | 65 Fantasy Adventures | Mervyn Peake | Lord Dunsany | H.P. Lovecraft | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Ursula K. LeGuin | Michael Moorcock | Gary Gygax | Clark Ashton Smith | Frank Frazetta | George MacDonald | John Bellairs | T.H. White | Wilkie Collins | M.R. James | Edgar Allan Poe | Lewis Carroll | Mikhail Bulgakov | Guy Endore | Alasdair Gray | Maurice Sendak | Tove Jansson | L. Frank Baum | Roald Dahl | Abraham Merritt | August Derleth | William Hope Hodgson | Madeleine L’Engle