Hardboiled Middlebrow

By:

September 4, 2009

Though Middlebrow wouldn’t triumph until midcentury, and though its most perspicacious critics would therefore be members of the Partisan Generation, its first flowering was on the Hardboiled cohort’s watch — and many of its most influential peddlers are members of the 1894-1903 generational cohort.

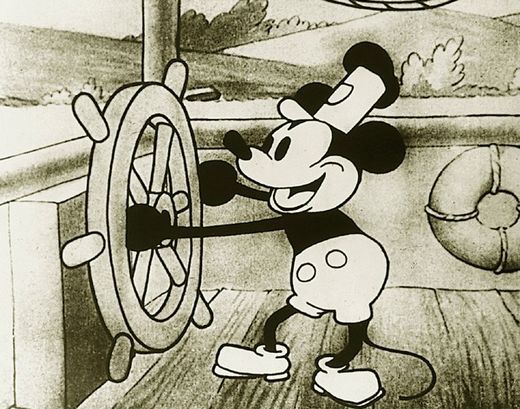

Which might explain why Strauss & Howe’s influential (and pro-Middlebrow) generational periodization scheme, which is obeyed slavishly by generational trend-spotting journalists and marketers, lops off the youngest members of the Hardboiled Generation and assigns them to the so-called GI or Greatest Generation (1901-24, supposedly). Why 1901? Because that’s when Walt Disney, that world-beating avatar of Low Middlebrow, was born.

This item is excerpted from yesterday’s essay on the Hardboiled Generation.

In every triumphalist middlebrow account of American history, things were going poorly until the so-called GI/Greatest Generation came along. Strauss & Howe are dismissive of the Lost Generation (actually the Modernists and older members of the Hardboileds), whose “selfishness and unreason,” “fatalism,” “stark nihilisms” (i.e., surrealism, Dada, expressionism, futurism, “Freudian relativism”), and “pessimistic theories” they contrast unfavorably (in their 1991 bestseller, Generations) with the “fearless but not reckless” manner of those “confident and rational problem-solvers,” the GI or Greatest Generation (actually the Partisans and the New Gods). Middlebrow, which deceptively styles itself as non- or post-partisan, approves only of those fictional generations that eschew fretting about subjective forms of unfreedom and focus instead on getting the job done. In the 20th and 21st centuries, that means the so-called Greatest/GIs and the so-called Millennials.

Boomers, like Strauss and Howe, worship the Greatest and Millennial Generations. Members of the deluded Boomer generation, that is, are forever kicking themselves for not being more middlebrow than they already are.

All of which explains why Walt Disney, that master of cutesying up fairy and folk tales, national cultures, and real-world locales (i.e., the raw ingredients of ideology, which is to say resistance to the soft tyranny of Middlebrow’s hegemonic discourse), must be plucked out of his own generation (the Hardboileds) and assigned to the Greatests .

Further study of the semi-hopeful, semi-fatalistic Hardboiled Generation might provide useful clues — useful to saboteurs, that is — regarding the subtle mechanism that keeps Middlebrow ticking.

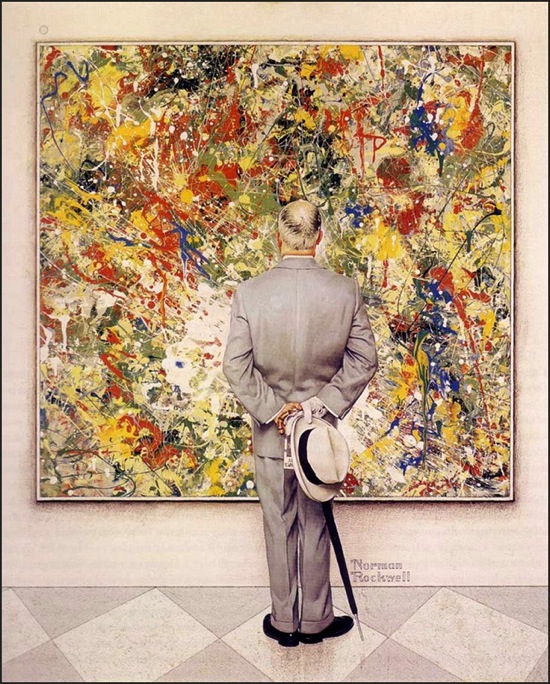

This is not the place for such an investigation, but let’s just take note of the fact that Walt Disney, along with fellow Hardboileds Norman Rockwell, Bernard De Voto, Norman Vincent Peale, Robert Maynard Hutchins, Mortimer J. Adler, Mark Van Doren, and Thornton Wilder are among those who first either attempted to synthesize the energies of Highbrow and Anti-Lowbrow, by hustling a ham-fisted attempt at cultural and intellectual achievement known today as High Middlebrow; or who synthesized the energies of Lowbrow and Anti-Highbrow and cranked out a variety of wildly successful low middlebrow (i.e., semi-hopeful, semi-fatalistic) cultural productions, from Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers to Wilder’s Our Town, to — you know — all things Disney.

In fact, it can be extremely difficult — now, even more so than then — to distinguish pre-midcentury middlebrow productions from the non-middlebrow cultural milieux out of which they first emerged. Adorno and Edmund Wilson were perhaps the only critics born before 1904 who even attempted to do so; and for their troubles they’ve been castigated as “mandarins” and “elitists” — i.e., by middlebrow critics posing as populists — ever since.

To the untrained eye, and to blunted sensibilities, there’s not a great deal of difference between Fleischer Studios’ Betty Boop, say, and Disney’s early Mickey Mouse cartoons. Yet the latter are middlebrow, Adorno and Horkheimer insist in their essay on the Culture Industry in The Dialectic of Enlightenment (though unlike Dwight Macdonald, who was influenced by Adorno’s criticism, they don’t use that term), while the former are not.

If this judgment outrages you, then imagine the scorn poured on Adorno for having dared to criticize jazz and certain films that we admire immoderately today (noir films, for example); or on Wilson, who reviled popular mystery novelists (Agatha Christie, Rex Stout) and the beloved J.R.R. Tolkien (“Oo, Those Awful Orcs”)! One’s admiration for these early, courageous anti-middlebrow critics grows by leaps and bounds.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).