The Manuscript of Belz

By:

August 31, 2009

THE LIBRARY IS collapsing on itself, trying to digest itself. Renovation has turned the whole place into a vast construction site, where tradesmen build temporary walls surrounding temporary walls surrounding temporary walls, ad-hoc postindustrial labyrinths lit by bare bulbs encroaching on the bookstacks. Construction workers come into my office daily, sledgehammering pillars and propping them up again, removing thermostats, ceiling lights, and flooring. It’s out of this maze of dust and incandescent light that Brko emerges, bearing apologies and a manuscript — the apologies for his intrusion, and the manuscript for his enrichment. Then again, I suppose that’s what his apologies are really for, too.

Brko is a construction engineer; he wears a hard hat with some a troubled Balkan state’s flag taped to it. Day after day in the bowels of the library he demolishes walls with a front-end loader. I’ve seen him stumping down the halls, sweaty and swollen-faced, but haven’t spoken to him until today. When he enters, I think he’s here to knock the thermostat off the wall again. But he says nothing, only gazing at the stacks of old, leatherbound volumes heaped up on my desk. After awhile, he says, “my book is more beautiful than this. I can show you?”

I smile and nod, thinking how little ever comes of such offers. But yes, I tell him, I’d love to see it, of course.

“It is here,” he says, handing me a dingy manila envelope.

But I thought it was a book, I say.

“Well, yes, it is piece of book. A page. But it is very beautiful. You look, maybe library will to buy.”

The single leaf slides out easily; singed fragments of paper rain down upon the floor. But yes, it is beautiful — a nearly whole first page of a richly illuminated manuscript. I sit awhile stunned, burned by the iridescence of the gold leaf, the blue whorls of the abjad.

I want to know where Brko got it.

“Before I came, I was driver,” Brko says. “I drove for UN, for journalists, for others, too — mostly at the end for UN inspectors. Someone gave to me. I knew it was beautiful. So I kept.”

I wonder what else he knows about it.

“It comes from town called Belz, it had mosque, it had beautiful manuscript. Interior troops hit town hard, they break mosque down and burn. This the only page who survived.”

I gaze a bit longer before handing the piece back to him. It is beautiful, yes, I say. But we surely won’t acquire it. We don’t know its provenance — we can’t know its origin with any certainty — and besides, it’s incomplete, and badly damaged.

At this, Brko’s face turns red. “Is this library telling me this, or you only? I am happy going someplace else.”

I nod apologetically. No no, I say. I am no expert. I will show your manuscript to someone who is. And Brko slips the envelope on my desk and backs away, his head swaying to and fro.

“Then we will see,” he says. And with that, he exits.

I place a call to the curator of manuscripts. She’s not answering, so I leave a voice mail and try to put the envelope out of my mind, to no avail. Late in the afternoon, I withdraw the delicate leaf from its sleeve and place it in a yellow puddle of lamplight. It is Ottoman, no doubt, masterfully done and prodigously well-preserved; the parchment fresh, the ink all but moist. But where would it have come from, what sort of a place?

A little village in the rain. It always rained on Belz. This would have been the lore of the region, the prejudice against Belz, and the residents of the town would have shared it, even taken a perverse pride in it, perhaps. Why do I imagine such a downpour? Maybe I’m trying to forestall the fires, the bombing and burning that await the town and its manuscripts. In any case, with the rain as with so much else, things had been this way as long as anyone in the country could remember. Even through the most difficult times of the Federated Republic and all that had followed, right up until the Nationalists took power, Belz would have been the same: a small town of white flaking walls, red tile roofs, and running gutters, framed by the chalky bulk of the mountain looming white among the clouds. Nearer to town would have stood the walnut orchards with their silken worm-bags hanging in the branches, the air pungent with the pulp of the fallen walnut husks mellowing in the Belz rain.

In the center of town stood a mosque built of chips of stone taken from the mountain. It was very old, and had been beautiful once, the white rocks laced together with black mortar. During the Federated Republic, the stones of this same mountain, which in places bore the rough graffiti of Roman occupiers, were used all around the country to cover hillsides with great white letters that read out slogans like PARTY AND PEOPLE and the Grave Leader’s name. These stones were Belz’s second claim to fame — though the residents of Belz were dubious of their renown in this matter, having been the conscripts who had carried those chips down the slopes in heavy baskets.

In the Federated Republic, the mosque had fallen out of use and into disrepair, and now it was a museum of sorts. Among a few old coins and shards of classical earthenware, it contained Belz’s third most famous property, after the rain and the stones: the Manuscript of Belz. The people of Belz with their wet shoulders and their runny noses took great pride in this artifact, this venerable book of scripture filled with calligraphy and ornamented with gold leaf and brilliant illuminations. Scholars came to Belz from as far away as the capital city to view and study the book. The town kept a small cell adjoining the display room in good repair, that scholars might have space in which to work and to spend a few nights if they so wished.

An old man, who fancied himself the keeper of the book, visited the mosque regularly to tidy the room and to attend to the scholars’ needs. Though he could not make out the writing it contained — the old calligraphic styles never were prized for their legibility — he nonetheless loved to fondle it as it lay in its velvet cradle under glass. He made a ceremony of turning over a leaf of the manuscript each morning; this he did first thing, before going to the cell to dust its floor beams with a stiff broom. Sometimes he ran his rain-cracked fingertips over the loops and serifs of the characters, feeling the ridges the ancient pen had made as it had cut into the paper. He stared down at the illuminations, taking off his skullcap of roughly knitted wool and twisting it in his fists as he gazed wonderingly into the book.

When the Nationalists took power, the residents of Belz had cause to worry. Although they were not at all political — the Federated Republic and its Grave Leader had taken care of that — the Nationalists hated the Muslims, hated their skullcaps and their dark eyes, hated their distaste for pork and strong liquor, hated the harsh fricatives of their dialect, all so reminiscent of the heretical empire of old. Though to tell the truth, the Nationalists would have hated Belz even if its people spent their days bare-headed beneath the cloudy skies, drinking vodka and eating ham sandwiches.

The curator of manucripts arrives, interrupting my reverie.

“Let’s have a look at this forgery your friend has brought you,” she says as I hand her the envelope.

A forgery, I ask? That’s too bad. Of course, I’m not surprised to hear it.

She slips the page from its cover, and the scent of burnt hide fills the room. “I’m being unfair,” she says. “It’s not precisely a forgery — more of a facsimile, really. And as the story goes, it was produced for the best, most quixotic reason. You see, the people of the town knew that the army was destroying all the Islamic objects they could find, and they wanted to save their manuscript. So they hired a conservator who knew the manuscript well, and he produced a facsimile for them. The idea was to replace the original, to leave the fake for the soldiers to find.”

So if this is the fake, I wonder, what happened to the original?

The curator shrugs. “No one knows,” she says. “According to the prevailing opinion, the conservator must have absconded with it. But Belz was razed only a couple of years ago. The volume could still turn up, intact, in an auction somewhere.”

What about Brko’s piece, I ask.

The curator holds the piece at eye level, letting the lamplight plane off the prismatic text. “It’s shockingly good,” she says. “I’ll take it back to the lab for a closer look, just to be sure. But you’ll probably have to tell him he’s got a fine conversation piece.”

The people of Belz knew that the Nationalists had begun their cleansing; they saw tall stalks of black smoke rise and blossom on the horizon. And the old man knew — for visiting scholars had told him — that the Nationalists would burn the manuscript if it fell into their hands. He brought the problem before the town council, who, naturally, were divided over the matter.

“They won’t bother us here,” one said. “When have they ever?”

“What about the young men?” one asked. “Each day another one goes to join the fighters in the hills. The troops will come when they find out about this.”

“Couldn’t we send the manuscript along with one of these boys?” someone asked in reply. “My nephew leaves tomorrow, nothing I’ve said will stop him.”

“But what if he’s caught?”

“My son is planning to pack his family and leave the country,” said another. “He could take it with him.”

“But they’ll be stopped and searched at the border!”

“No no, the Interior Police won’t bother with a simple family mulecart!”

“How can you hope to beat these thugs at their own games?” cried an older man. “When the troops arrive, we should welcome them with gifts of bread and salt in their custom. We should bow to them and hand over the manuscript. That way they won’t burn our houses!”

“But no one can burn the houses of Belz!” someone said. He stood and shook his fist. “Our rain will stop them!” he shouted, and the crowd replied with hoots and peals of laughter.

The old man, who had stood patiently in the middle of the chamber through it all, shook his head, put his finger to his nose, and spoke. “I have a plan. Years ago a young scholar visited us. Now, this scholar, whose name was Fadim, I remember that he was also an artist. He told me that he knew how to write in the ancient calligraphic style of the manuscript, that he could bind the leaves into a book and sew a grand leather cover. Though this man had once worked in the capital city, he left when the university closed. He lives now with family not far from Belz. Now this Fadim, perhaps we can entice him to come, to make a facsimile of the manuscript that we can turn over to the police in place of the original.”

The council argued awhile longer, but finally agreed to do as the old man suggested. The next day he borrowed a battered sedan from one of the councilors and drove over the pitted road to find Fadim and ask him to Belz.

Fadim was unhappy on his cousin’s farm: afraid of the animals, repelled by the smells of the barn, he insisted that plowing and sowing should not be allowed to wreck his scholar’s hands with a stick of wood for being such a useless wreck did he at last join in the work of the farm. He took refuge in solitary tasks, and even came to enjoy milking the cow — her udder leather-dry, her milk the same creamy yellow color as paper. Such opportunities for reverie were far-flung, however, and he passed through his days on the farm as if they were so many abandoned rooms. He squinted at the dirty children, cursing the country silence and the frozen stupidity of his cousin’s people.

When the old man arrived from Belz, Fadim was perplexed. The venerable fellow made a strange ambassador, after all, with his moist skullcap and his sniffles. But at his first mention of Belz, Fadim’s heart fluttered. His breath caught at the thought of the famous manuscript. And when the old man explained his mission, his invitation buoyed Fadim at once. He did not need to take a second glance at the bruised farm lying all around him before saying yes to the old man. He was careful, however, to mask his eagerness to leave, and his hunger to have the manuscript in his hands once again.

“We cannot pay you,” the old man said. “But you will have use of the mosque, and free board for as long as you need.”

Fadim pinched his chin and shook his head. “How much time do we have?” he asked. The old man only shrugged, for who could know? Perhaps the troops would never come — or perhaps they were in Belz already.

Fadim grumbled about his family and his duties on the farm, just to make a show of it. But in the end, of course, he told the old man he would come. It didn’t even matter that Belz couldn’t pay him, as the country’s money was worthless. Belz offered honor, though, greater honor than he could ever find prodding his cousin’s muddy sheep to return to their fold. So Fadim told his cousin he was leaving (the man only wiped his brow and spit on the ground) and packed a worn valise full of tools and materials and a bottle of cream fresh from the morning’s milking. He placed his valise in the back seat of the sedan and settled in beside the old man, who sat behind the wheel eating a raw, peeled onion. The old man steered the car over the road, chattering on in his onion-scented fricatives about all the scholars who had ever visited Belz.

Belz welcomed Fadim like a martyr. The rain had dwindled to a premonitory mist; boys jumped up and down along the road playing their boom boxes as the car bumped up the steep hill toward the mosque. Some men roasted a goat while women linked their arms and danced in the muddy yard. The old man accompanied Fadim everywhere, smiling broadly and patting him on the back. Finally, he led him into the moist innards of the mosque, led him to the neat cell with its high desk and its window looking out on the gray skies and the houses of Belz fringed with the yellow-leafed crowns of the walnut trees. As the rain hammered the chipped stone wall outside, Fadim unpacked his needles and silken threads, his inks, and his pots of pigment and powdered gold.

Fadim began the labor thinking that his work need only be reasonably accurate. The Interior Police were infamous illiterates, criminals released from the state prisons, and easily fooled. Any antique-looking book full of flourishes would satisfy their flames. But as he studied the manuscript — removed from its glass case and placed in its velvet cradle atop the high desk —Fadim was charmed once again by its sublime script. He read the holy words as if for the first time, and the manuscript spoke to him. He inhaled the incense of its antiquity — the dry, spiced scent of moldering paper and leather — until, when he fell into bed at night, he could smell it on his hands and in his hair. The figures of the script sang, made sounds of words the likes of which he had forgotten. How could he have missed all this beauty on his first visit to Belz? He was young then, of course, his graduate studies barely finished. And now, after all that had happened to him, he could see fresh milk and smell wet fields among the pages of the ancient text. In thrall to all this voluptuousness, he longed to reproduce it. He wanted nothing less than to recreate the Belz Manuscript — he would have stayed in that cell and made a thousand of them; he would have drawn and gilded and folded and sewn until he fell dead from the stool, had such a thing been possible. He would have filled the world with Manuscripts of Belz until they were plentiful as plums. And when the work was finished and the new manuscript lay atop the table beside its older twin, it seemed all the more glorious for its freshness. It lacked the scent of the old book, of course, but even that would come in time.

The ringing phone interrupts my reverie. It’s the curator of manuscripts.

“I have, well, interesting news, and then I have bad news,” she says. “Bad news first: as I said, and as you thought, we can’t really use the piece. It’s fine, really, a first-rate example of the illuminations from its period. We can’t firmly substantiate where it’s from, as the manuscript was never microfilmed. So we don’t know enough about it to curate it. But now, here’s the interesting part: it’s the real thing. It’s not a facsimile. It’s a genuine fifteenth century Ottoman manuscript, a fragment of the Koran, in fact.”

You’re kidding. That’s incredible.

The curator snickers into the phone. “You can tell your friend Brko to get in touch with me,” she says. “I’ll set him up with the someone at Sotheby’s.”

I remember that the Koran is an attribute of Allah, as perfect and eternal as His beauty, His anger, and His mercy.

I hang up the phone and stare at the heaps of books around me. Walls of precious, rare codices, safely imurred in my library. Somewhere nearby, Brko knocks down a wall of bricks, and dust sifts from still more tomes as they tremble imperceptibly on their shelves. I suppose I should be surprised that Brko holds a piece of the original manuscript — that for all his attempts to pass a fake as the real thing, it proved to be authentic after all. Then again, perhaps the whole story of the facsimiles was a hoax, a confidence man’s clumsy parable concocted to pique buyer Brko’s interest.

I can’t let go of Belz, though, or Fadim. I feel sure that Fadim was real, and that he had to betray Belz in the end. For would you not have felt, as Fadim must surely have felt, that such a work — a work of one’s own hands, after all, the consummation of a lifetime’s perfection of the rarest and most esoteric skills — could never be given over to the flames? Surely this is what Fadim felt. And surely this is why, on that last wet morning before the sun had risen, he padded softly out of the mosque with the manuscript, the new Manuscript of Belz, wrapped in a kerchief in his valise. He slipped down the hill and splashed out onto the road, ignored by the dogs who yawned and shook off the rain as he passed.

That very same night, of course, the tanks and armored trucks of the Interior Police had climbed the hills on the outskirts of Belz. They paused now among the walnut trees on the edge of town. Young men with shaven heads and blue eyes passed the hours smoking furtively and watching the lights of Belz flicker in the rain. They were eager for the sun to come up and their work to begin, for fighters from the hills had struck hard in the capital city, and the soldiers knew what revenge they would seek in the damp town below them.

As the sun rose, the soldiers swiveled their rockets and fired at the mosque. The shells slammed into its walls, shaking them shrilly, clapping them like bells. Thick smoke poured from the white rock walls. The soldiers rushed into town with the tanks close behind. They gathered Belz men, still bleary-eyed from sleep, and began sorting them out. Any man with rough hands and tanned skin they judged a fighter; they pushed these men against walls and shot them in their faces. The councilor who had argued appeasement now tottered bareheaded from his house, offering bread and salt in his raised hands. A soldier hit him in the head with the butt of his rifle. Soldiers caught women hiding in root cellars and raped them. They burned the low silos and they shot the milk cows while the stones of the mosque rolled and cracked in the flames that incinerated the famous manuscript and the old man, who died asleep in his cell. As sour smoke curled among the piles of rubble, soldiers laughed and took turns firing across the fields at townspeople running into the walnut orchards. Those running through the fields did not notice how the sun, rising for once in a clear sky, had warmed the dew in the grass.

The soldiers caught Fadim as they were driving out of the uprooted town. He had hidden in a bank of grass along the road where the rocket tanks had stopped, and had been too frightened to move. As the tanks churned through the ditches and over the road one made straight for him, forcing him to run, and the soldiers pointed their rifles at his head. A young soldier, deprived of spoils by his comrades, demanded that Fadim give up his valise. Convinced by his pallor and the softness of his hands that he was no fighter from the hills, the soldiers told him to go away. As they drove Fadim off with taunts and blows, the young soldier prised open the case, spilled its contents into the mud, and cursed to find nothing of value.

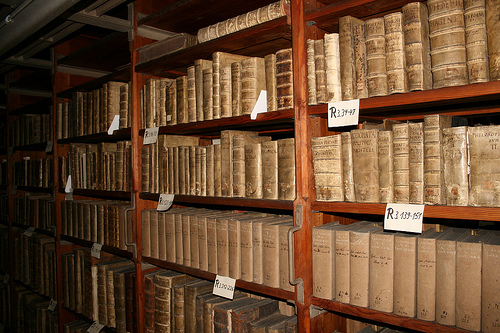

This story first appeared in September 2000 on hermenaut.com; it’s published here with a nudge from Peggy Nelson. The photograph of bookshelves in the Älteste Bibliothek of Halle is in the Flickr stream of gynti_46 and is used here under a Creative Commons attribution/share-alike license.