Laylah Ali: Doodler

By:

August 24, 2009

Another postscript to Matthew Battles’ meditation on doodling. I originally wrote this item for Laylah Ali: 5 Responses to 5 Paintings, an exhibition brochure published by the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2002.

Late one night in 1968 — just a few weeks before my friend Laylah Ali was born — Eldridge Cleaver stepped out of his car, unzipped his pants, and began to pee onto a deserted Oakland street. An entire squad of police officers suddenly materialized, and an amplified voice ordered the Black Panther Party’s Minister of Information to put up his hands; he reached down to zip himself up, and a bloody shoot-out ensued. When he got out of the hospital, the ex-con was indicted on charges of assault with intent to kill, and shortly after that he was instructed to report back to prison. Cleaver fled to Algiers instead, where he told an interviewer: “I believe that there are two Americas. There is the America of the American dream, and there is the America of the American nightmare. I feel that I am a citizen of the American dream, and that the revolutionary struggle of which I am a part is a struggle against the American nightmare, which is the present reality.”

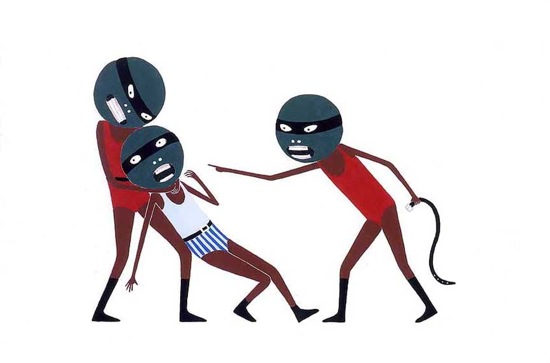

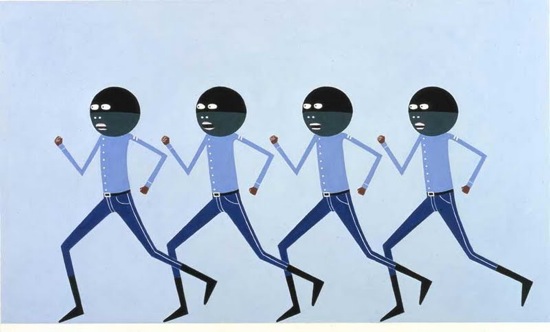

Many artists have attempted to depict in images the so-called American Nightmare, which is to say everyday life under what Cleaver described as “the racist, capitalist, imperialist, neo-colonialist power structure,” and critics and curators alike have tended to agree that Ali’s paintings are merely a contemporary development and extension of this tradition. The naive, almost cartoon-like style in which she presents tableaux of Greenheads in uniform, ecclesiastical robes, and mufti confronting, interrogating, torturing, and executing their fellow Greenheads has been interpreted as an ironic strategy on Ali’s part; she is, we’re reminded again and again, a member of the most pop-culture-damaged generation yet.

But Ali rejects these too-easy interpretations. “The ‘psycho-political’ is where the psychological meets the political,” she’s explained, “and both converge in my studio space.” If these paintings are devoid of any natural or social context, it’s because the Greenheads inhabit a negative zone between the artist’s unconscious and the world outside; their motivations are as mysterious to the artist as they are to the rest of us. Those thugs clutching belts in their gloved hands aren’t in the employ of the Capitalist Ruling Class, then; nor are the paramilitary types jogging around in tight formation Imperialist Lackeys; nor are the whiskey-priest blackcoats in basketball shoes, the ones who look a bit sheepish about their own incompetence, Agents of Neo-Colonial Oppression.

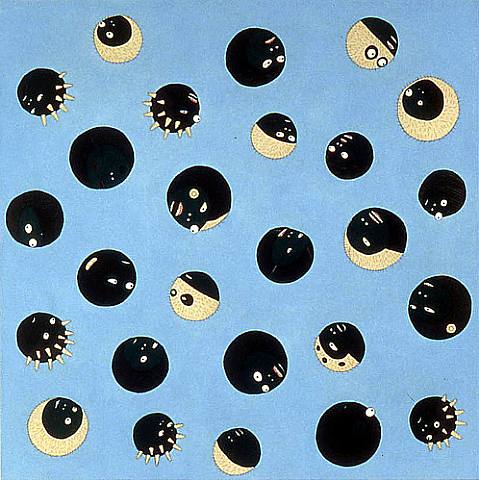

The Greenheads are neither signs nor symbols. They’re doodles: semi-conscious expressions of our collective, frustrated utopian dreams.

The Greenheads actually began as doodles, scribbled in the margins of Ali’s notebooks during boring art-school theory lectures. First came the big round heads, and later the brown-skinned bodies, dangling loosely down underneath like balloon strings. After a while, some big-headed doodles began to restrain other big-head doodles, with trusses and chains. Eyes, legs, and arms were plucked out or lopped off, and little “flesh”-colored Band-Aids applied to raw wounds and incisions. Drawn in a kind of fugue state, this is the stuff of nightmares: terrifying, but also absurd.

So perhaps Ali’s stubborn willingness to renounce realisticism points us toward a solution, of sorts — one which Cleaver, who’d found himself in a waking nightmare in which the world was out to get him, and in which his zipper was unzipped too, articulated at the conclusion of the above-mentioned interview. “What happens to people in the United States is that they are given these dreams and then they are put through a very subtle process of twisting and deformation and brainwashing, and they really have no defenses against this process because it’s done by a very elaborate structure,” Cleaver explained. “Our struggle is to make a demarcation between the dream and the nightmare. And that’s all I’m saying, and that’s all I ever want to say, because that’s all that is important, you see.”

Ali’s paintings aren’t calls for direct action, nor are they ironic riffs on Revolutionary Art. Like the fugitive individual in one of her own paintings — the one standing in an attitude of wary readiness, face covered by a balaclava like the one worn by Subcomandante Marcos of the EZLN — Ali is a twenty-first-century guerrilla, concerned less with radical politics than with outwitting that “elaborate structure” which prevents us from abandoning the American nightmare for the American dream.