In Praise of Doodling

By:

August 24, 2009

Preliterate, primordial, the doodle is at once the most common and the most ignored art form. And yet for all its primitivity, and despite its surely universal occurrence among the literate peoples of the world, there was no English word for the behavior we now call doodling until the middle of the twentieth century. The Oxford English Dictionary (which defines the doodle as “an aimless scrawl made by a person while his mind is otherwise applied”) cites a source for the first use of the word doodle in the familiar, autohypnotographic sense — Russell M. Arundel, who in his 1937 book, Everybody’s Pixillated, defines the doodle as “a scribble or sketch made while the conscious mind is concerned with matters wholly unrelated to the scribbling.” Arundel makes the claim that civilized man’s natural state is one of “pixillation” — a condition of pixie-like enchantment that, though concealed by the lumber and business of modern life, emerges most clearly in the “automatic writing” he calls “doodling.” To prove his point, Arundel catalogues the doodles of midcentury notables — the likes of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Cab Galloway are represented — with thumbnail psychological workups of each one based on elements of doodling style. Arundel finishes with a “pixillation chart” that taxonomizes major doodling motifs, allowing the reader to gather an accurate picture of his own fey subconscious. Someone who scrawls rhyming words, for instance, is “poetic in nature and a lover of music”; the mere “repetition of words and letters,” on the other hand, “indicates you are cynical or morbid.”

After Arundel, doodle quickly appears in popular magazines, such as Life; in 1942, Punch described Labour M.P. Clement Attlee as a maker of “doodles of intricate pattern.” By 1947 the word is available to Auden, who in The Age of Anxiety describes “memories stuffed / With dead men’s doodles.” Doodle, it would seem, possesses that handy sort of oddball appropriateness that quickly finds a home in everyday language. Like Nerval’s apocryphal lobster, the doodle may be strange — but it does not bark, and it knows the secrets of the deep.

While our current sense of doodle is relatively new, it is an old word. In his Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson defines a doodle as “a trifler, an idler,” calling it a mere “cant word” and suggesting that it derives from the expression “do little.” Later dictionaries, however, trace it from the Portuguese doudo, for foolish, or more plausibly from the Low German dudel, as in dudeltopf, a nightcap (an etymology that crosses aptly with that of “dunce cap,” so named for the medieval Scholastic philosopher Duns Scotus, whose aversion to classicism earned the derision of Renaissance schoolmasters). The best-known such use occurs in the colonial sobriquet “Yankee Doodle,” which may have originated as a Dutch New Yorker nickname for Anglo-American colonists — with Yankee from the Dutch New Yorker Janke, or “Johnny,” which in turn became a catchall British nickname for Americans during the Revolutionary War. By the late nineteenth century, it is used to describe a cheat; and gradually “doodling” becomes the name of idle, deviant, or erratic behavior. In America the term took an entomological turn, denominating the larval ant lion, or “doodle-bug,” whose apoplectic fits of excavation gave it a reputation for prophecy or second sight like that enjoyed by madmen and sibyls. Ever the expert folklorist, Mark Twain uses the doodlebug in Tom Sawyer: when a magic ritual fails to return to Tom his lost marbles, he turns to the insect’s divinatory powers to reveal the cause:

… he searched around till he found a small sandy spot with a little funnel-shaped depression in it. He laid himself down and put his mouth close to this depression and called:

“Doodle-bug, doodle-bug, tell me what I want to know! Doodle-bug, doodle-bug, tell me what I want to know!”

The sand began to work, and presently a small black bug appeared for a second and then darted under again in a fright.

“He dasn’t tell! So it WAS a witch that done it. I just knowed it.”

Tom’s Bacchic tendencies would seem to endow him with a doodler’s impulsive nature. But Huck’s is the idle and playful mind; with Tom, by contrast, indolence is never without purpose. In the midst of a dreary school day in an earlier chapter, for instance, Tom passes the time by drawing on his slate a picture of a house with a man and woman — but this is no doodle; he makes the drawing to win Becky Thatcher’s attention, promising to “learn” her the art if she’ll meet him after school.

Around the turn of the century, doodle goes dormant, disappearing altogether from standard consumer-grade dictionaries like the Webster’s Third Collegiate. When it finally re-emerges, it attaches its baggage of madness and prophecy to the sober arts of writing, daubing, sketching, and inscribing. Before the twentieth century, the nearest term was scribble — a word with an obviously Latin origin that came into use, seemingly coeval with widespread vernacular literacy, in the late Middle Ages. But scribbling is not doodling, because scribbles are marks made in haste or by an uncertain hand. Doodling, by contrast, is beyond craft and criticism; it belongs to us all; it’s impossible to do it badly — or well. It springs from that flourishing thicket, common to everyone, where mind shoots forth its florid branches from the rootstock of the animal brain. Its intent, if it has one, differs from the preliminary brainstorming of sketching and the territorial mark-making of graffiti: it is the graphic expression of ennui, an existential criticism of the world-as-such.

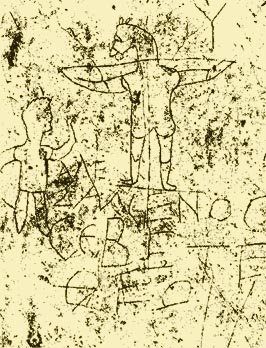

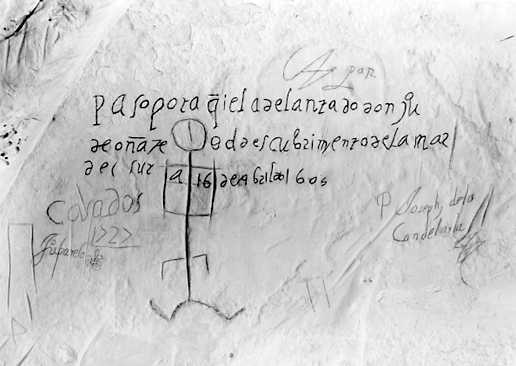

And yet, even if our sense of doodling emerges only in a post-Freudian perspective, evidence for graphic thumb-twiddling stretches back through the millennia. The tablets of Mesopotamian apprentice clerks, their edges decorated with epithets and images poked irresolutely into clay now long dry, betray the doldrums of the scribal college day. Writing inscribed in ceramic, unlike marks on paper, lasts for centuries; thus were these most ancient ephemera preserved for the ages. Despite differences in media, doodling behavior is remarkably constant over time; in medieval manuscripts, margins are filled with serpentine scrollwork or a scribe’s name written over and over. These marks are different from glosses, marginalia, and fabrications, which flower like poppies amid the uncial harvest of medieval manuscripts; those, by contrast, guide reading, study, and interpretation. But for the practical monks, even doodling had a reason: their term for the practice was probatio pennae, the “proving of the pen.” And yet there is the whiff of an excuse behind this term, a hiccuping attempt at vindication: for often the ragged columns of names go on too long to be the product of anything but the doodler’s idle urge.

In its modern sense, doodling is surrealism and abstract expressionism’s dour bachelor uncle — a workaday, intuitive expression and proof of the conviction that the artist is coextensive with nature. And the power of all art, furthermore, is bound up in our empathetic experience as doodlers; great art returns our doodles to us with a kind of alienated majesty. It was Emerson who said this, referring to the works of great thinkers — in whose complex, polished, and ramified ideas we may discern the traces of our own abandoned musings.

The young Emerson, in fact, was a prolific doodler. As he matured, however, this studied and self-regarding man was careful to purge his journals of all that would not be of use in essays, lectures, and poems. It’s often supposed that the doodles of esteemed authors might help to explain the origin of their talent. But of Emerson’s early doodles little can be said. Composed when the Sage of Concord was a middling student in Harvard College, they are indistinguishable from any boy’s adolescent jottings: ships, amiable lancers, and piratical profiles predominate. And yet it’s somehow more comforting to find nothing but the pure old graphic impulse gratified without tinge of greatness. Emerson would have been the first, I think, to agree that doodles drop from the Over-soul; their origin is somehow corporate and transpersonal. This is why bibliographers, who have learned to count and classify the meaningful marks of authors, printers, readers, and redactors, largely pass over the doodle in silence. If a doodle has anything to tell us about the creative work of its author, then it isn’t a doodle.

But if doodles have nothing to say about their creators as authors or artists, they do tell stories about them as people. We doodle in solitude, fixing styles as private as the individuated, inner cosmologies of thought that betray themselves in the slow smiles or the clouded faces of strangers on the subway. I have the most intimate evidence at hand: my father’s doodles are typographical, filled with bulked-up capitals and ballooning logograms of obscure intent; my wife, who is a computer programmer, doodles intense, fractal mappings of non-Euclidean spaces; and as for me, I fill notepads with calligraphic whorls, filigrees, and unbalanced, pillowy arabesques, which I suppose are crude evocations of an antiquarian penmanship.

But I hesitate to ascribe meaning. For like all doodling, mine is about anything but expression. Its joys are sensuous and immediate: the dry catch of the pencil point as it tangles in the fibers of the page, the gelid smoothness of the ballpoint unrolling a fat swath of ink, the pliant bouquet of crayons and the stink of coloring markers. It should be counted as a windfall, a private feast of roadside berries, that doodling offers a fossil poetry as well.

This article first appeared in Autumn 2004 issue of The American Scholar.