Double Exposure (6) — Food Fight

By:

August 16, 2009

Michael Pollan, author of The Botany of Desire (2001), The Omnivore’s Dilemma (2006), and In Defense of Food (2008), is a highbrow. I say so not because he’s a graduate of Bennington, Oxford, and Columbia who deftly translates complex subjects from co-evolution to “nutritionism” into journalism-ese, but because — despite his ever-increasing influence when it comes to hot-button issues around the food we eat and serve to our children — Pollan remains resolutely Apollonian. Like all highbrows, Pollan punctures our religious and faddish devotion to the mythology of simple solutions via recourse to careful scientific research. And his rhetoric is always moderate: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

The complementary position to Highbrow is, of course, Anti-Lowbrow. In the screeds of romantic anti-agribusiness (“corporate farming”) critics, everything from contemporary farm practices, seed supply, agrichemicals, and food processing to marketing, advertising, and retail sales aren’t merely in need of reform but wicked: inauthentic, perverted. Pollan is also a critic of agribusiness, and a champion of sustainable farming practices. As a highbrow, though, he’s less extreme and uncompromising than the anti-lowbrows: he’s more empirical, less ideological.

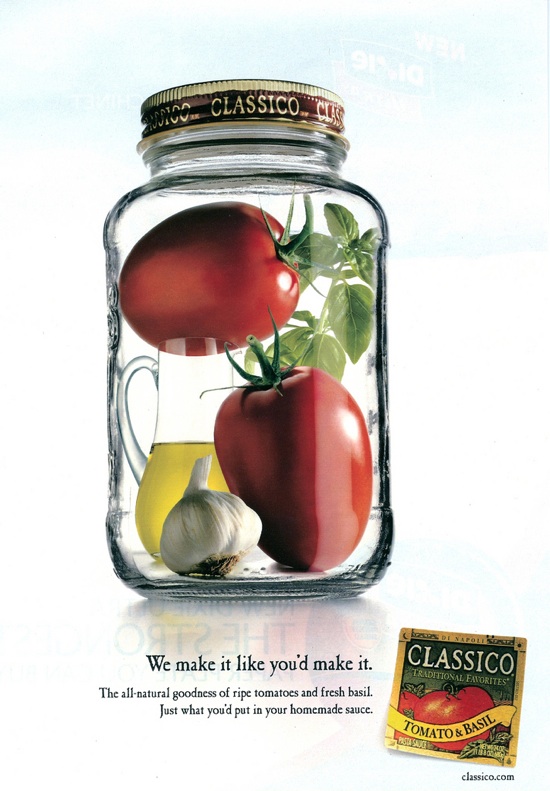

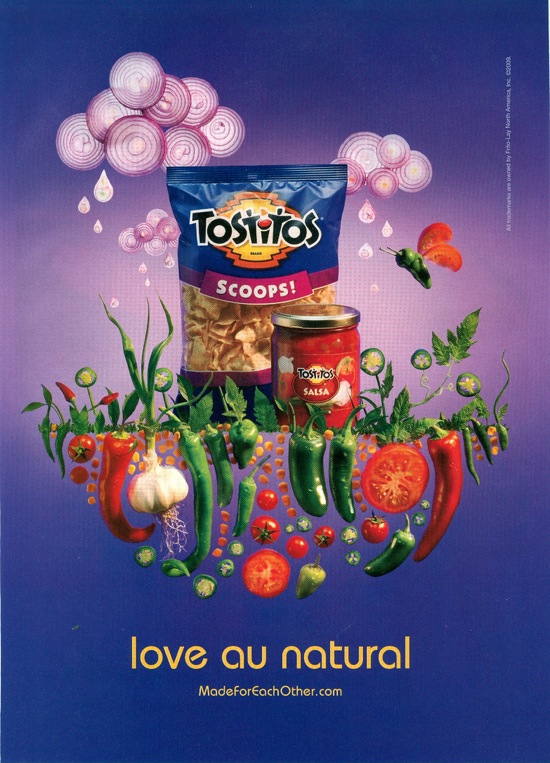

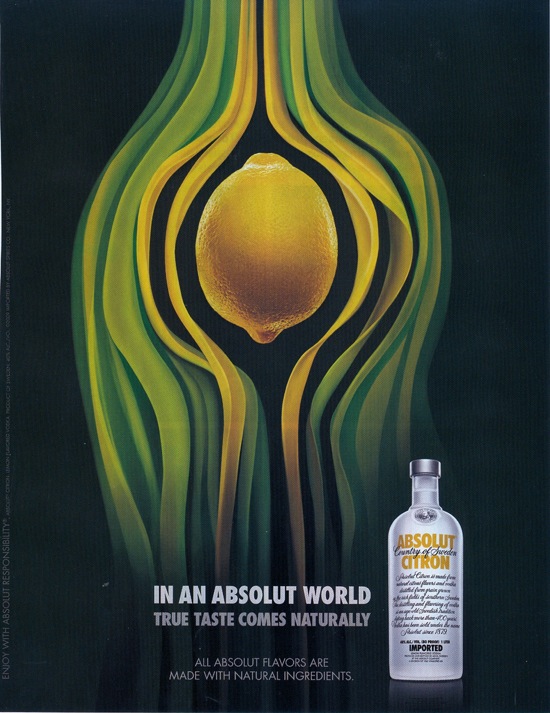

Seeking a gemütlich synthesis of Highbrow and Anti-Lowbrow, in food as in all other areas, Middlebrow currently offers a bumper crop of Rousseauvian advertisements in which foodstuffs are simultaneously fetishized and processed for mass consumption.

Why Rousseauvian? According to our research, Rousseau — who mixed elements from both the mainstream (highbrow) and radical (anti-lowbrow) Enlightenment in his philosophy — was the first middlebrow. So it’s no surprise to discover, in the advertisements shown here, idealized fruits and vegetables straight out of Rousseau’s wildly popular novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (1761): “Excellent vegetables, eggs, cream, fruit; those are her daily fare….”

Middlebrow’s message, which so many have found so convincing for so long now, always strikes the same note: semi-idealistic and semi-realistic. (Think of the early Neoconservatives who claimed they were “liberals who’d been mugged by reality.”) In the communications shown here, we discover the same old tasty recipe being prepared for us by the master chefs of Madison Avenue. The foods shown in these ads aren’t realistic but hyper-realistic, so true to life that they’ve become fantastical. This is Middlebrow’s preferred mode of visual representation, now.

Baudrillard, who is charmed by clumsy fakery, but creeped out by hyper-realism, describes second-order simulacra (like the tomatoes and garlic on this page) as a kind of technology employed by those (middlebrow) social forces whose relentless purpose is to terminate history itself — i.e., by eliminating oppositional elements (e.g., highbrow, lowbrow, anti-lowbrow, anti-highbrow) in society, and transforming the mass into “the silent majority.”

Which brings us right back to Rousseau, whose doctrine of the volonté générale, the idea that the common good can be judged by no criteria other than what best serves the interests of the silent majority), ought not to be confused with the authoritarian (anti-lowbrow, or anti-highbrow — extreme ideologies tend to resemble one another) instantiation of the doctrine adopted by pseudo-Rousseauvian revolutionaries such as Maximilien de Robespierre and the Abbé Sièyes. Rousseau’s own (middlebrow) conception of the general will is less authoritarian than that — therefore less charming, Žižek would insist, in his joshing, crypto-Baudrillardian way — but simultaneously more acceptable, more reasonable-sounding.

And, therefore, creepy. Like these ads.

This is the sixth in a series of posts reviving the practice of extispicy — i.e., divining the outlines of our invisible prison (formerly known as Fate) via a study of signs and portents found in the unlikeliest of places.

MORE SEMIOSIS at HILOBROW: Towards a Cultural Codex | CODE-X series | DOUBLE EXPOSURE Series | CECI EST UNE PIPE series | Star Wars Semiotics | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | Show Me the Molecule | Science Fantasy | Inscribed Upon the Body | The Abductive Method | Enter the Samurai | Semionauts at Work | Roland Barthes | Gilles Deleuze | Félix Guattari | Jacques Lacan | Mikhail Bakhtin | Umberto Eco