Hilo Heroes, June 28-July 4

By:

June 28, 2009

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, this week, to the following high-, low-, no-, and hilobrow heroes. Click here for more HiLo Hero birthdays.

My heart still skips a beat when I look at old Rolling Stone photos of GILDA RADNER (1946-89), an early childhood crush and, then as now, one of America’s greatest comediennes — and it still breaks when I think of her death from ovarian cancer at 42. Whether it was her malapropisms as Emily Litella, her primordial nerdiness as Lisa Loopner, or her general non sequitur insanity as Roseanne Rosannadanna, Radner breathed life into post-Nixonian/pre-Reaganite archetypes that will be forever indelible from our collective memory of the 1970s. The mind reels when thinking of her acting debut: the 1972 Toronto premiere of Godspell, starring Radner, Eugene Levy, Andrea Martin, and Martin Short. If I had a time machine, that would surely be my first stop. — Jason Grote

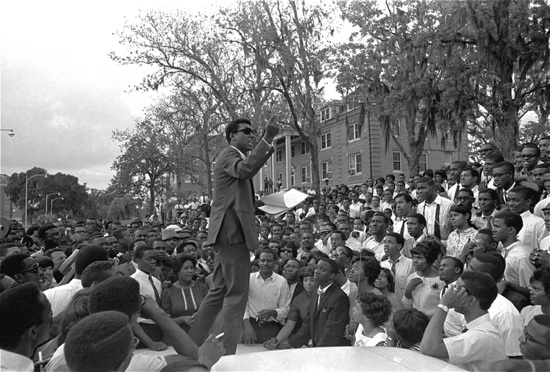

After the disillusioning Democratic convention of 1964, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee split into two factions, one of which favored nonviolent tactics and integration-oriented policies. The other, increasingly revolutionary faction was led by STOKELY CARMICHAEL (1941-98), a Trinidadian-born activist newly graduated from Howard with a philosophy degree; the era we know as the Sixties (1964-73, IMHO) began at precisely this moment. Influenced by Malcolm X and Frantz Fanon, Carmichael called for black Americans “to define their own goals, to lead their own organizations”; the Civil Rights Movement’s unintended function, he claimed, was to integrate blacks more securely into America’s invisible prison-state. His anti-anti-utopian vision of Black Power finally led Carmichael out of SNCC and out of the United States — he relocated to Guinea, and changed his name to Kwame Touré. For the rest of his life, he invariably answered the telephone with the same greeting: “Ready for the revolution!” — Joshua Glenn

For much of the 1940s, LENA HORNE (born 1917), Hollywood’s “sepia Cinderella,” was relegated to one or two set-piece numbers per film. Opulent, glamorous, and static, her turns in Two Girls and a Sailor and As Thousands Cheer bespeak segregation in action, but even these were risky at a time when so much as an eyeline match between black and white characters could get a scene (or a whole film) cut from Southern distribution. Among the revelations in Stormy Weather, James Gavin’s new biography of the singer, is that her career’s early direction owed no more to MGM than to the NAACP: her activist grandmother signed Horne up for the organization at the age of two, and it was political pressure that led Louis B. Mayer to place her under contract. In later decades, she grew far more independent, artistically and especially ideologically, admiring Malcolm over Martin, and telling talk-show host Mike Douglas that blacks and whites “don’t really need to love each other.” Eventually, she would speak with open bitterness about the studio system (and much else) in Lena Horne: Her Life and Music, her 1981 one-woman Broadway comeback. Gavin’s sleuthing suggests that Horne’s construal of events was as fantastic as any publicity hack’s puff piece — but this time, at least, the fairy-tale was of her own devising. — Franklin Bruno

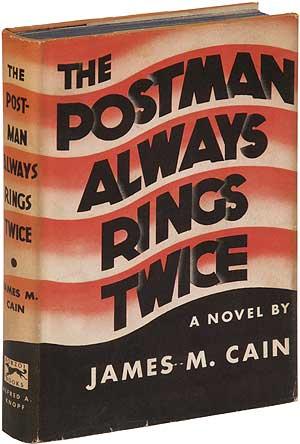

“They threw me off the hay truck about noon.” The celebrated first line of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) by JAMES M. CAIN (1892-1977) tersely illustrates his verbal and narrative economy as well as his acute ear for American speech, and suggests his compellingly driven use of the first person singular. Cain, who wrote about crime without being a crime writer, was instead a kind of sawed-off Zola, a stranger to mystery. His other great novel is Double Indemnity (1943), which symmetrically enough has a famous last line. (“The moon.” You’ll have to read it to find out why.) It was made into an equally indelible movie by Billy Wilder in 1944; the best adaptation of Postman is Luchino Visconti’s unauthorized Ossessione (1943). Also noteworthy are a few books that have something wrong with them: Mildred Pierce (1941), the deeply strange Serenade (1937), and the totally overlooked The Moth (1948). Cain was a classic instance of a novelist with only one story; the further he strayed from the fatal triangle the more likely he was to embarrass himself. — Luc Sante

Playing twins who change places, a teenager who swaps bodies with her mother, and a couple of appealing outcasts who find a way in, LINDSAY LOHAN (born 1986) once portrayed duality with an irresistible coarseness. Today, you can’t take your eyes off the paparazzi’s LiLo. Unlike her onetime friend, preeny Paris Hilton, through her pretty, pretty scowl and aviator shades Lohan radiates pure fury — the fury of a suburban teen. She still uses a teen’s strategies, too. The cocaine in her pocket couldn’t be hers, she told police in 2007 — they weren’t even her pants. She admitted to Vanity Fair that she had done drugs — “a little” — and you imagine her dipping a cocktail stirrer into a pile of coke and extracting one grain with her tongue. LiLo has spent more time in rehab than on movie sets; the 84 minutes she served of her one-day prison sentence apparently didn’t allow for much moral inventory. According to the movie industry, she’s “unemployable.” But don’t ask her whether she’s OK: “It’s like ‘Yeah, motherfucker, I’m fine.'” — Ingrid Schorr

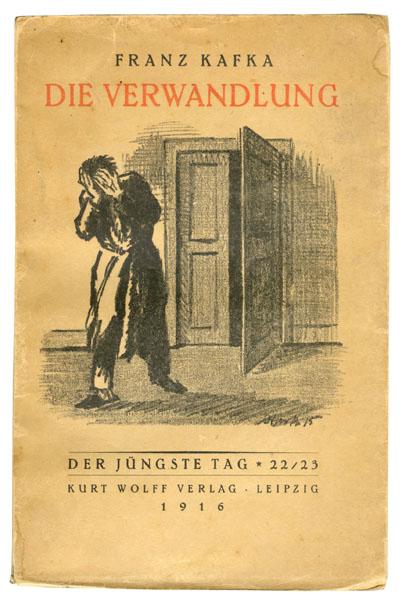

Patrick C. stared in silent disbelief at the bureaucrat who sat on the other side of the desk. Eventually he gathered himself and spoke in an exasperated plea: “You want me to write 150 words on FRANZ KAFKA (1883-1924)? How am I supposed to pay tribute to such an important literary influence in the space of a mere paragraph?” The bureaucrat stared back coldly. “You are required to write the piece. I’m not at liberty to tell you how or why.” Not for the first time that day, Patrick C. felt alone and defeated. Why did he have to do this? Why was nobody offering to help him? Should he focus on the novels or the short stories? And how would he end the piece? By noting the appropriate fact that Kafka, highly competent insurance clerk, wanted to render his existence as a writer totally futile by having all his work posthumously burned? Or by pondering on why so much of Kafka’s work remained unfini — Patrick Cates

Pulitzer prize-winning cartoonist RUBE GOLDBERG (1883-1970) pulls string (A) which activates bellows. Bellows (B) compresses, inflating balloon (C). Expanding balloon causes glass of water (D) to tip, soaking sponge (E). Sponge, due to increased weight of water, sinks, raising candle (F), which burns string holding back needle (G). Needle swings and pokes bird (H), which is tied to Goldberg’s pencil. Pencil (I) attached to Goldberg, who creates some of the most lasting and whimsical cartoons of the twentieth century, his machines becoming so indelibly part of the culture as to be honored with a dictionary definition all their own. — written and drawn by Joe Alterio

Pulitzer prize-winning cartoonist RUBE GOLDBERG (1883-1970) pulls string (A) which activates bellows. Bellows (B) compresses, inflating balloon (C). Expanding balloon causes glass of water (D) to tip, soaking sponge (E). Sponge, due to increased weight of water, sinks, raising candle (F), which burns string holding back needle (G). Needle swings and pokes bird (H), which is tied to Goldberg’s pencil. Pencil (I) attached to Goldberg, who creates some of the most lasting and whimsical cartoons of the twentieth century, his machines becoming so indelibly part of the culture as to be honored with a dictionary definition all their own. — written and drawn by Joe Alterio