Thirteen Ways of Looking at Apollo

By:

June 23, 2009

1

…Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

— Rainer Maria Rilke, “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” translated by Stephen B. Mitchell

WHEN HUMANS FIRST made their mark on the moon forty years ago, it was a moment that attracted the fascination of millions. And yet today its impact seems as remote as the flags, landing stages, and footprints left on Earth’s satellite by successive landings — footprints that no wind will wither. For all the optimistic hopes — that by the scope and grandeur of the Apollo program we would overcome our species’ many foibles; that through its mixture of Promethean energy and humble industry we would domesticate space itself — it was an ineluctably human endeavor, suffused with the tensions of myth. This moment of transcendence was shot through with one species’ peculiar habits of sense and attention. Even the choice of destination was parochial and impulsive; the moon, after all, is an insignificant body by any measure but our own. Watching the progress of Apollo, many boggled at the distances and speeds involved, the incomprehensible abysses we could now leap with our machines. And yet didn’t we discover, looking back home over the desolation of the moon’s horizon, that even such distances were as nothing in the vastness of space? That even with great expenditure of energy — colossal, flagrant, unparalleled in history — we were still stuck in our own backyard?

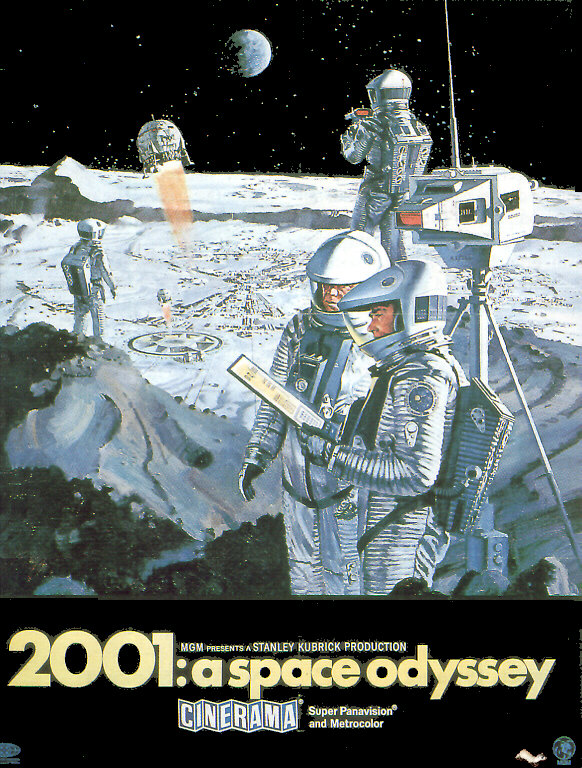

In the lens of retrospect, the moon landings appear as some island culture that flourished briefly and then vanished, leaving only ruined towers, ritual costumes, and incomprehensible glyphs. In the decades since, NASA’s ambitions for manned space exploration have been comparatively middle class. Apollo by contrast was always more a work of art than an expedition; it was the prototypical space opera, the only one carried out on the very stage itself. Next to it, all manned endeavors in space since have been akin to sideshow or vaudeville. Like classical Greek drama, Apollo’s moment is gone, and some of its rituals, its choruses, will never make sense to us again. The age of easy space travel that Apollo seemed to promise never materialized; the jet-setting, space-hopping life envisioned in films like 2001 seems as spectacularly misbegotten as visions of skies dominated by Zeppelins and flying cars.

At the time, some thinkers believed the moon would be disenchanted by our visiting it. Yet it remains suffused with a brilliance that seems to come from within. Even in a world in which there is no place which does not see you, the moon remains inscrutable, unperturbed. Forty years after a small band of humans set foot on the moon, a great cohort of our species have become astronauts of a kind, and the planet we visit is our own. Our mission controls have moved to office parks in Louisiana and call centers in Mumbai. We climb into the hermetically sealed capsule of our vehicles, which we navigate by satellite. We wear on our belts tiny computers with more processing power than those used on the whole of the Apollo program. We’re wired up with earbuds, heart monitors, mobile phones, and laptops. RFID chips in our ID cards talk to the network and track our movements. As we shoot thus encapsulated from place to place, the systems hum; distant servers chart our progress; chatter bounced off satellites keeps us company. Across what used to be called the digital divide, meanwhile, typhoons sweep away villages, rice crops wither, and children kill each other over bundles of firewood. And yet “their” problems seem “our” problems, their sorrows our responsibility. It’s this aspect of Apollo’s legacy that says, you must change your life.

2

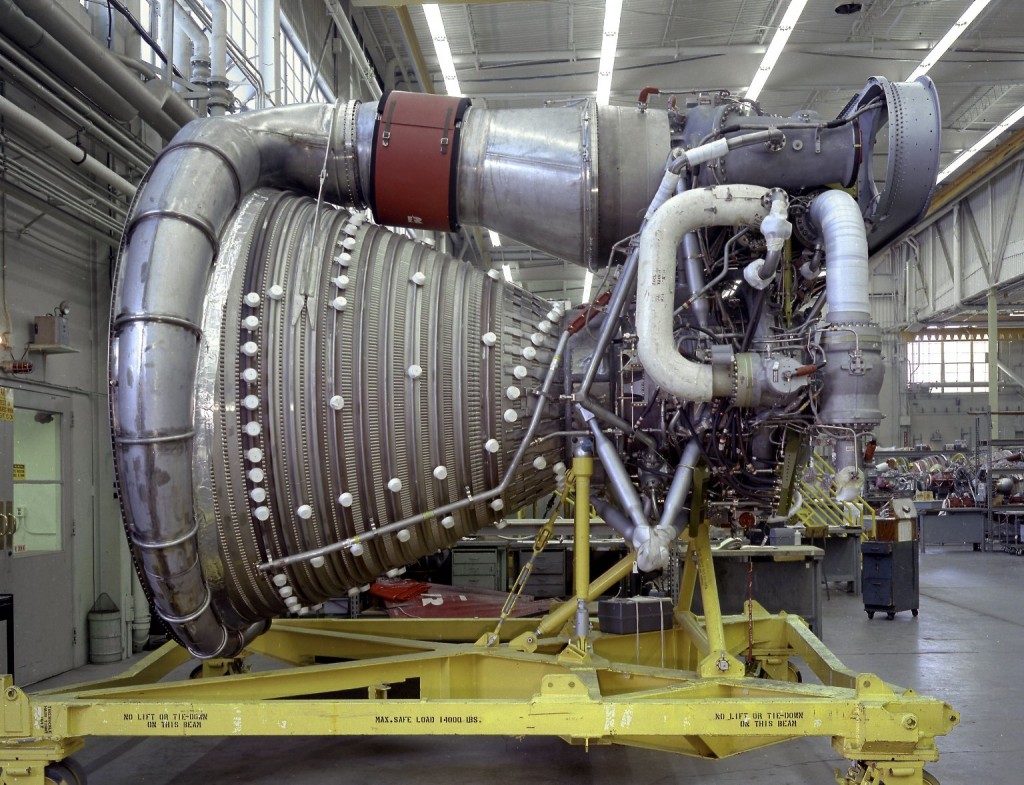

The craft the Apollo astronauts rode to the moon was a capsule of contradictions: an engineering marvel and a jury-rigged bucket of bolts, a pill-like pod of corrugated metal contrived to give its aviator-cum-astronauts the feel of flight in an airless environment; a symbol of existential enigma and loneliness in which each system, no matter how minute, had its operators and monitors and simulation-ready counterparts on Earth. The command module would travel further from home than any vehicle heretofore, and yet its subtlest changes would be watched and scrutinized to an unprecedented extent. Apollo was a congeries of machines aimed not only at the moon, but at one of modernity’s primary questions: to what extent will the tools we create come to dominate us?

In a sense, Apollo was a giant confidence game played against the astronauts — one so successful that it gulled us all. The astronauts came from the world of test pilots, the testbed of machismo and consummate skill, the attitude depicted by Wolfe in the Right Stuff. But even for these skilled and talented men, space flight proved too complex. The calculations required to maintain attitude even in the simplest trajectories are at once elegant and mind-boggling in their permutations, and the speed with which they must be carried out is beyond all human possibility. But the astronauts demanded control — and they had their swagger, the adulation of the public, and the fact that it was their lives on the line to back up their argument. In the end, Apollo’s systems would give them the illusion of complete control, responding to their instructions, their movements of sticks and switches.

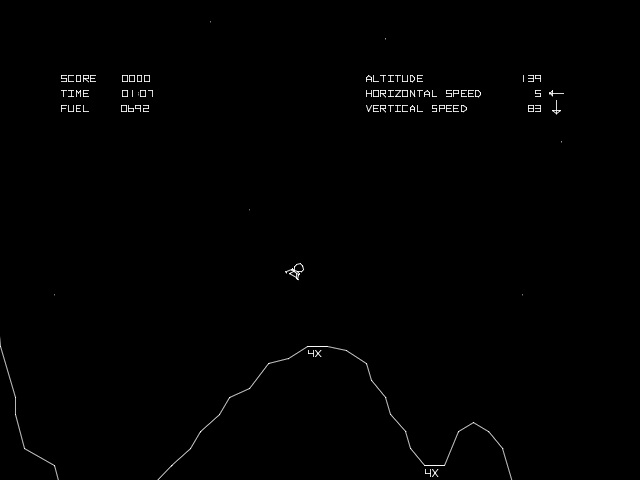

It’s an intoxicating notion, piloting across the star-studded reaches of space. The drama of the Apollo landings — all of which were accomplished under manual override of automatic systems — was evoked in the classic Lunar Lander video game. When Luke in the climactic battle of Star Wars turns off his targeting computer and dives at the Death Star with eyes closed, The Force merges with The Right Stuff. In fact, Apollo’s computers aided the intuition of their pilots, figuring out in milliseconds how to do what the astronauts wanted to do. Jim Lovell used star sightings to navigate Apollo 8 to lunar orbit and back. But on subsequent missions, the NASA planners would never again trust the astronauts to drive their craft to the moon unaided.

3

Norman Mailer was especially touched and perplexed by the problems of the astronauts. “They were virile men,” Mailer writes in Of a Fire on the Moon,

but they were prodded, tapped into, poked, flexed, tested, subjected to a pharmacology of stimulants, depressants, diuretics, laxatives, retentives, tranquilizers, motion sickness pills, antibiotics, vitamins, and food which was designed to control the character of their feces. They were virile, but they were done to, they were done to like no healthy man alive…. On the one hand to dwell in the very center of technological reality . . . and yet to inhabit — if only in one’s dreams — that other world where death, metaphysics, and the unanswerable questions of eternity must reside, was to suggest natures so divided that they could have been the most miserable and unbalanced of men if they did not contain in their huge contradictions some of the profound and accelerating opposites of the century itself.

To Mailer, alienation was the century’s theme, and Apollo was but a grand fugue played on it. Certainly the revelatory power of the moon was at risk. Astronaut Pete Conrad admits to him that having “dreamed” of going to the moon for years, as an astronaut “now the moon is nothing but facts to me.” Mailer trumpets his decision to found a new psychology, the “psychology of Astronauts, for they were either the end of the old line or the first of the new men.” In fact they were neither the beginning nor the end — they were in the midst of a change older than the century, more comprehensive than machines. It was system, not machine, that was alienating us — and technology is at most system’s handmaiden. System is what deranged Melville’s Bartleby and Kafka’s dreaming, hapless clerks; and system, not machinery per se, is what made Apollo. So the machine, despite all its mercilessness, its coolness, its implacable thingness, is no obstacle to dreaming. Indeed for the planners and politicians who made the space race, these are the machine’s very attractions, the source of inspiration. Mailer imagines an American male regarding the moon shot:

He has worked with machines all his life, he has tooled cars to the point where he has felt them respond to his care, he has known them and slept beside them as trustingly as if they were hunting dogs, he knows a thousand things about the collaboration between a man and a machine, and he knows what can go wrong. Machines — all the old machines he has known — are as unreasonable as people…. He has spent his life with machines, they are all he has ever trusted…. He will see a world begin where machines are king and he does not know whether to cry from pride or (from) the all-out ache that he does not really understand the new machinery.

4

In 1963, not long after JFK issued his famous injunction to reach for the moon by the end of the decade, C. S. Lewis wrote that the first lunar landing would rob the moon of its meaning. “The immemorial moon,” he wrote, “the moon of the myths, the poets, the lovers — will have been taken from us forever…. Artemis, Diana, the silver planet belonged in that fashion to all humanity: he who reaches it first steals something from us all.” And yet even this attempted theft has its mythopoetic grandeur. While its ambitions were Promethean and Faustian, its rhythms and otherworldly reach evoke an Orphic strain, that of the trickster and tale-teller — Loki, Odysseus, the Haida Raven, even beanstalk-climbing Jack — who finds a way to the world of the clouds and the realm of the gods to steal golden eggs or a goddess’s golden hair, the beloved dead, or the light.

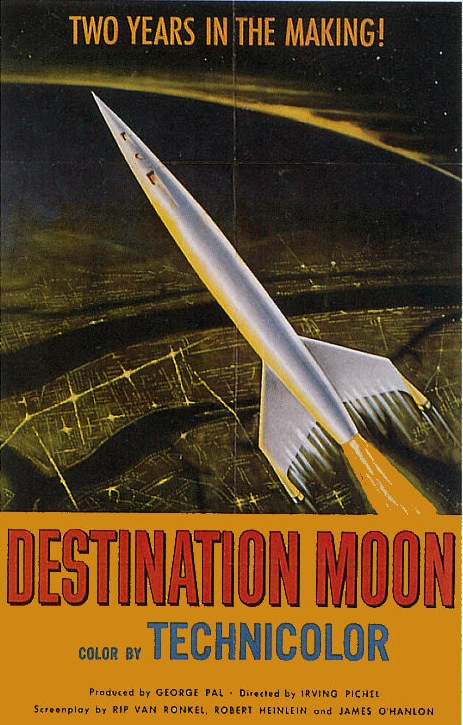

Except that this time it was no trickster who stole the moon’s light. Since Galileo realized that the moon is no inscribed disk or embodied spirit but a place of mountains and plains, the prospect of a visit to the moon has captured the imagination. But in story it is the poet and dreamer — not the warrior or the master builder much less the test pilot or the engineer — who makes the imagined first landing. In modern times, images of lunar voyagers partook of the Victorian conceit that explorers, like Richard Burton or David Livingstone, should be well-spoken rakes, men of letters as well as men of action (and men above all). Jules Verne imagined the moon conquered by a group of boastful gun enthusiasts. In C. S. Lewis’s first venture into science fiction, Out of the Silent Planet, the problem of interplanetary travel is conquered by a pair of poetry-quoting dons who build a rocket in their garden. Not until the 1950 film Destination Moon was a lunar voyage depicted as an enormous techno-industrial effort of the scale Apollo would assume. Science fiction author Robert Heinlein contributed to the film, which was based on his books Spaceship Galileo and The Man Who Sold the Moon, both of which featured renegade industrialists of Ayn Rand stripe who defy government restrictions in pursuit of their lunar ambitions.

With Heinlein as with the ancients, the moon was the goal of renegades, misfits, and outriders; it was not a place for the establishment. The Apollo astronauts too had their Odyssean side — they were men of many ways, the boys with the brightest teeth and the longest forward pass. But although the systems that powered them to the moon were designed to give the astronauts the appearance of existential wanderers in the vastness of space, their arrival on the moon was the triumph of engineers and computer scientists who found the ways to send steel and glass and air and water into the void and bring it back again. Who is the god of the engineers & the bureaucrats? What spirit presides over this hijacking of magic by engineering and administration? The Romans had gods for these energies of mass society: there was Securitas, who presided over state security, and even Cloacina, goddess of the sewer works (and for the Roman engineers, the underground was like our outer space, a world beyond to be tamed). The true pioneers of the space race, from Werner von Braun to the MIT engineers who designed Apollo’s guidance system, were descended neither from Gilgamesh nor Achilles (much less Orpheus). Their forebears were viziers and clerks, the crafty subordinates who devised agriculture, writing, and the phalanx.

5

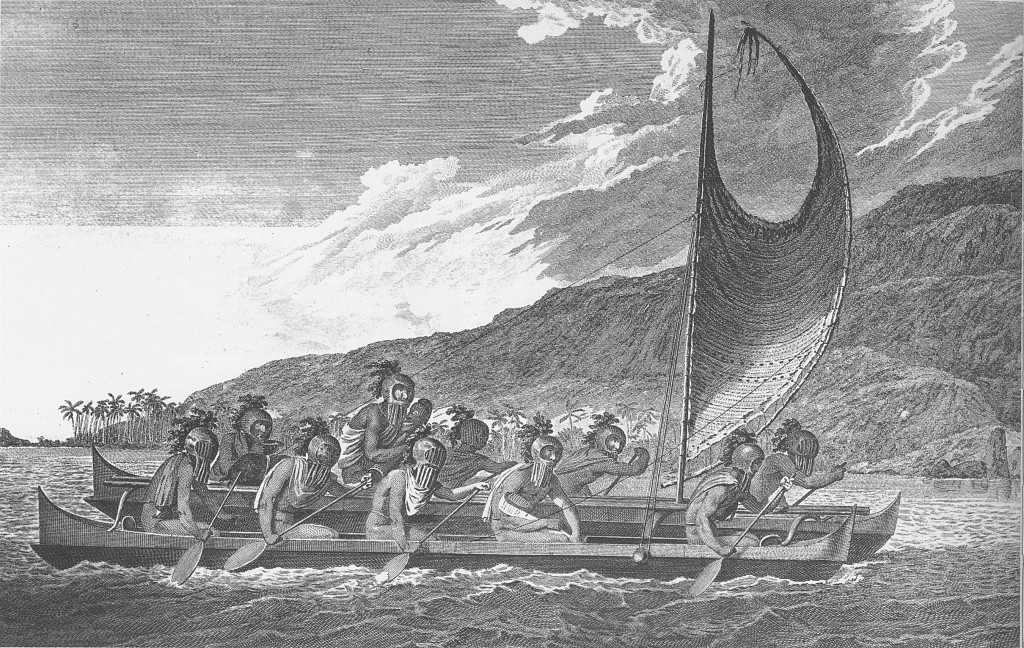

Apollo’s technology — its millions of parts, its hundreds of inventions, its theretofore unimaginably complex integrations — from today’s perspective make a fascinating blend of sophistication and brute simplicity. The Apollo guidance system included a “space sextant” which the navigator used to sight on fixed stars or features on the Earth and moon; for all their craft’s space-age sophistication Apollo astronauts relied on the ancient practice of celestial navigation to keep it on course. One of the engineers on the MIT team that designed the Apollo Guidance Computer was in fact a descendant of Nathaniel Bowditch, author of The American Practical Navigator (still in print) and an eighteenth-century authority on steering by the stars — a practice that would have been familiar to Polynesian mariners lacking writing, metallurgy, and the wheel.

Those Pacific voyagers wove their charts of wickerwork and shells; the positions of the astronauts’ stars were woven into the “core ropes” of physical memory that comprised the programming code of the Apollo guidance computer. Unlike today’s software, the programs the computer needed to run Apollo’s systems weren’t merely sets of arbitrary symbols written transferably on magnetic media. They were tangible, material things — assemblages of fine wire threaded through magnetic loops, the ins and outs of which represented the ones and zeroes of code. The resulting “ropes,” woven by retired millworkers in Massachusetts, weren’t mere text, but textile — densely woven, thumb-thick hawsers of cable snaking in and out of the on-board computer. To change the software, engineers needed not only to rewrite the code, but to weave new ropes.

6

If Apollo’s computer put a new spin on ancient technologies, in other ways it was starkly innovative — less the heart than the face of a new machine. Much derided today — compared to early PCs and even pocket calculators, its processing powers were minuscule — the Apollo Guidance Computer made use of a new concept, the interface, to adapt its powers to the astronauts’ use. The calculations needed to transport a manned vessel to the moon and return were dazzlingly complex and interdependent, a tapestry of celestial maps, Newtonian physics, and chemical and electrical engineering. While many NASA engineers wanted all of this calculation done on the ground, pressure from astronauts compelled planners to devise ways to monitor systems, calculate variables, and navigate and steer from onboard the spacecraft. Previous computers were autonomous; they were architecture; they were places. To interact with a computer even in the late sixties was to program it. On the Apollo missions, however, the astronauts would use computer software as a set of “tools” that were “embedded” in the machine. Engineers designing the computer were given one cubic foot within which to accomplish their task.

But with this wondrous efficacy, the machinery so loved by the American male was changing fundamentally; it was at once becoming more obscure and more intimate. On each Apollo mission, the Lunar Module pilot would assume control of the craft during landing — but the control was partial; the stick he manipulated also talked to the computer, which made numberless infinitesimal adjustments to his inputs. Apollo doesn’t create the shift to cyborg life; it only marks it, serves as its archetype. Perhaps the time is swiftly coming — indeed has arrived — when machines will search space not in our stead, but as our extensions. Mariner, Voyager, Odyssey — these are tools; they descend from flint axe and firebow.

Hannah Arendt understood that the limits of our machines were bound up with our own possibilities. She pointed out that computers could only replace our cognitive labor; they could never on their own take up the world-making work that goes by the name of wisdom — a habit of mind that needs a wanting, feeling, failing body to make it whole. Apollo was a product of the long struggle to step outside the blinkered viewpoint of the human, to reach what Arendt called the “Archimedian Point” — the vantage from which all nature could be abstracted and objectified. In the space race Arendt saw the drama of this struggle entering a crucial stage — indeed its tragic one. For she surmised that from the moon we would look down only on ourselves; that each step in the conquest of space would only redraw the borders of our parish, our domicile, our prison.

Tools themselves have never delivered us from our disappointments, and they never will. Consider HAL, the interface that was also the artificial malevolence at work in 2001. HAL embodied a fear that has been with us since the start of the machine age, but he also effaced the functional late-sixties mystery of how computers would help us do our work. Behind HAL’s red eye was a black box — indeed the ultimate black box, that of the human pysche with its needs and passions.

7

Not only in its technology but in its images and its cultural effects, Apollo is a marooned legacy. How do we place the energies and emanations of Apollo amidst the bloody kaleidoscope that was 1969? From today’s vantage point it’s hard to reconcile images of the lunar program — a combination of austerity, hope, and sheer power — with the spectrum of tragedies that turned the counterculture’s transformative possibilities into a tissue of rage, desire, and self-annihilation. But these images were very much on the minds of Apollo’s critics, as well as its planners, its engineers, and the astronauts themselves. Hardly a public announcement of progress in the program could be made without pious admonitions to turn the energies of innovation and the spirit of exploration loose on the problems of an Earthbound human race. As engineering historian David Mindell points out, while frontier images and Right Stuff machismo resonated in Apollo, it was also a time of increasing fear of technology running amok. Lewis Mumford had coined the term “megamachine” to describe “the aggregate of technology, social organization, and management.” 2001: A Space Odyssey, which appeared in 1968 — and which the astronauts watched in part to prepare themselves for a lengthy sojourn in deep space — conjoined the futurist optimism of Arthur C. Clarke and the dystopian hopelessness of Kubrick’s view of mankind. Clarke thought we could perfect ourselves by going to the stars; Kubrick knew that no salvation was possible. Though their views of our prospects were very different, Clarke and Kubrick shared a sense that mankind was inherently flawed.

Such a meeting of contrary sensibilities was hardly limited to the creators of 2001, however. The angry dichotomies of political and cultural life in the sixties revolved around questions of our capacities for change and how to seek it. And in time it would be the counterculture, despite its criticism of the colossally misspent energies of Apollo, that would embrace the vision of Earth from space.

8

The astronauts of Apollo 11 and the later landings would bring back rocks and dust — handfuls first, and then great heaps; nearly nine hundred pounds of lunar rocks in all. The astronauts’ specimens are kept to this day in controlled vitrines, bathed in nitrogen to prevent their corrosion in the Earth’s atmosphere. But these shards are orphaned, their shimmer faded (ironically, they’re ultimately fragments of the Earth, as the moon itself was shorn from our planet by a massive impact billions of years ago; in the final analysis, the lunar rocks have come home.) Mailer ends Of Fire on the moon inspecting a fragment of lunar geology behind its double panes of glass at the Lunar Science Center, apostrophizing it as a long-lost lover or a virgin mother. It’s fair to say the moon has kept its unimpeachable magic; in its unchanging revolutions it is as baleful and benevolent as ever. Its influence remains undiminished by a trampling of footprints, however giant they may have been for Mankind. The one truly magical artifact brought back from the moon was made by the Apollo 8 astronauts: the famous photo of Earth’s swirling whites and blues set against the burnished grey plain of the moon. The picture Bill Anders shot through the one unfogged window of his capsule was quickly dubbed Earthrise — and yet it captured the imagination not of a rising, but of a setting world. Historian Robert Poole points out that this was a view imagined by the ancients, anticipated by modern internationalists, and claimed ultimately by the environmental movement as a transcendant symbol of the living planet as the final commons.

9

O thin men of Haddam,

Why do you imagine golden birds?

Do you not see how the blackbird

Walks around the feet

Of the women about you?

— Wallace Stevens, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”

10

Mailer, like Lewis, feared that Apollo would rob the moon of its glamour. By the magic of Apollo it was not the moon but the Earth that we lost. No longer is it Turtle Island, the fundament, the enduring core; we’ve seen it for what it is: a bubble, a mote. Spaceship Earth, in the pre-Apollo coinage of Buckminster Fuller. Robert Poole points out that the astronauts saw something similar to the Earth of Plato’s imagining: “variegated, a patchwork of colours of which our colours here are, as it were, samples that painters use. . . . Even its hollows,” Plato supposes, “full as they are of water and air, give it an appearance of colour, gleaming among the variety of other colours, so that its general appearance is one of continuous multicoloured surface.” For all Plato’s world-eschewing idealism, the ultimate ideal is perhaps the Earth itself; we’ve always been our own heavens.

But once the image’s inspiration had cooled, once the hyperbole had died down, we were left with the realization that the Earth’s resources are finite. Are we fellow travelers on Spaceship Earth? Or survivors cast adrift at sea, fighting for the last scrap of food, the last swig of sweet water?

11

“Spaceship Earth” was a concept that fit well with Buckminster Fuller’s philosophy of engineering and design driven by natural forms. Fuller approached Earth as a sort of broken vessel which it was our job to repair and keep well. Perhaps more than any designer or engineer or science fiction author, Fuller recognized that we were all astronauts already, that Earth is not merely in space but of it. Many commentators, from Arthur C. Clarke to Anthony Lewis, by contrast, had seen humanity’s move to space not as a chance to know and love the Earth better, but to leave it and its legion miseries behind. By 1968, clearly, the twentieth century had brought those miseries to what seemed an apocalyptic head; with the world wracked by famine, conflict, and the prospect of nuclear annihilation, it seemed we couldn’t break free from Earth’s bonds fast enough. With riots in the ghettoes, the moon shot looks like a step towards the ultimate white flight, getting out of the neighborhood before everything goes to hell.

And yet some recognized that even in its straitening harshness, the Earth provided a unique protection to the life that had evolved upon it. In War of the Worlds, for instance, H. G. Wells saw that the Earth was no mere vessel, but a protector of its living creatures as well. In the end the Martians die of bacterial infections against which humans had long been inoculated; “by the toll of a billion deaths,” he writes, “man has bought his birthright of the Earth.”

12

“The medieval notion of the earth put man at the center of everything,” wrote Archibald MacLeish in a New York Times commentary that many believed was the best early distillation of the Apollo moment. “The nuclear notion of the earth put him nowhere — beyond the range of reason even — lost in absurdity and war.” By achieving the moon, MacLeish paradoxically hoped, we would discover a new humility — a humility born of the very recognition that this mythic act was manufactured, made by working men and women with the tools at their disposal. “This latest notion may have other consequences,” he offered. “Formed as it was in the minds of heroic voyagers who were also men, it may remake our image of mankind. No longer that preposterous figure at the center, no longer that degraded and degrading victim off at the margins of reality and blind with blood, man may at last become himself.” No longer at the center; no longer at the margins, man becomes himself. We were in the midst of that becoming in 1968, and it was a complicated becoming — and Apollo was but a piece of it. We were learning how to accept our reflection in technology. MacLeish goes on to say that “To see the earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold — brothers who know now they are truly brothers.”

13

Two months later, Arthur C. Clarke in the pages of Look magazine predicted a blazing future for man in space: “Many of the children born on the day Apollo 8 splashed down,” he wrote, “may live to become citizens of the United Planets.” Born on December 22, 1968, I am one of those children; my father cried as he listened to the Genesis broadcast on the radio while driving home from the hospital after my delivery. The Apollo 8 command module itself ultimately found a home in Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, where I visited it throughout my childhood. The connection of the moon shot and my December nativity filled my imagination in those years; I was just old enough to watch and remember the later Apollo missions, when astronauts tore up the lunar surface in the rover and Alan Shepard hit his golf shot out of the biggest bunker in the solar system. The years that followed brought little but frustrating news from the space program; by the time we sat in the school library and watched Christa MacAuliffe and her fellow astronauts disappear in a spidery plume of smoke over the ocean in 1986, it seemed unlikely that I would ever have my passport stamped on the moon, much less Mars or the outer planets.

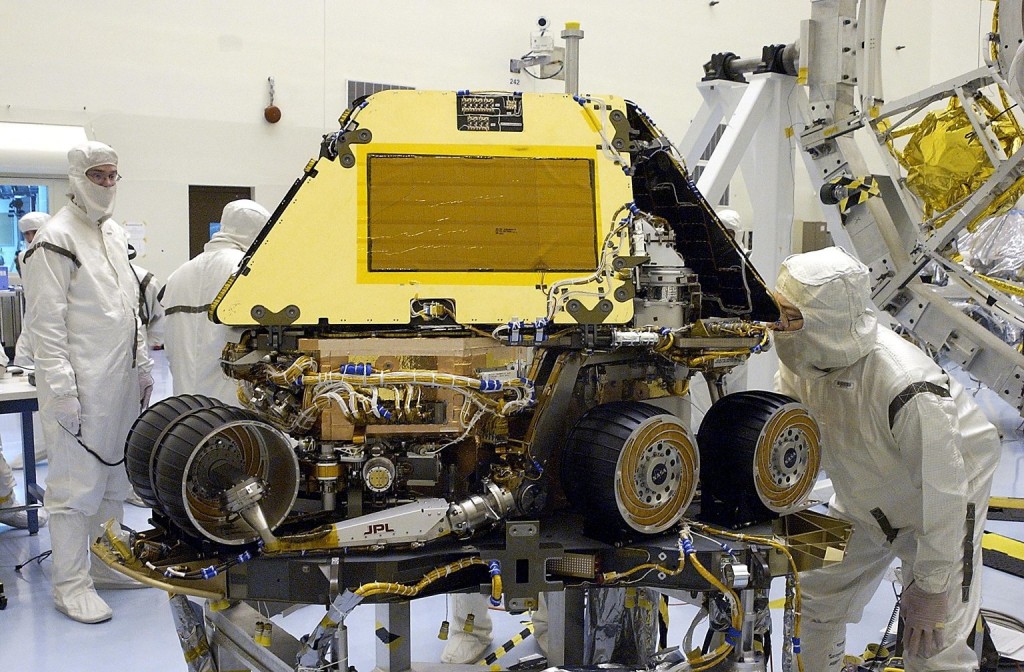

And yet the view from space now dominates the imaginings of us Earthbound astronauts. We download satellite imagery with the flick of a mouse; our unmanned craft even now speed among the outer planets, sift their sediments for signs of life, and probe the edge of the solar system itself, millions of miles from Earth where the sun’s influence finally ebbs. We’ve embodied that self-regarding wonder in the tools of exploration themselves: the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity, like their forbears Viking and the Voyagers, have captured the imagination of millions with their inexhaustible adaptability. The Voyager probes carry burnished plaques with human forms engraved upon them, an acknowledgment, however inchoate, that they are our interstellar avatars. Like WALL-E, the plucky robot star of last summer’s popular movie, the probes are tricksters and explorers, adaptationists, machines of many ways. As conjectured in the first Star Trek film, in which Voyager 6 returns to our solar system as a demiurge called “V’ger” striving to merge with its creator, they are latent gods as well. As with Apollo, of course, we’re fooling ourselves a bit — the Mars rovers are not autonomous adventurers, but long-distance tools controlled by hosts of engineers and scientists here on Earth. But using their aid not only to probe and explore but to adventure and to dream, we may be taking another kind of giant leap.

Once we sent humans into space to give a focus to our imagination; we needed heroes to embody our passions and our frailties. It’s by virtue of machines, however, that we have reached beyond the moon. Machines can compute but cannot feel; they express our intentions but cannot share our passions. Such has been the understanding, and the dilemma, of modern times. But perhaps we’ve underestimated the machine — which is only another way of saying that we’ve underestimated ourselves. Dimly, we’ve begun to realize that as we extend ourselves with tools, we inhabit them with our dreams and desires as well. Perhaps as we probe the reaches of interstellar space, we’ll feel more keenly the extension of our senses by even such abstract and remote tools as these. We’re coming to the point where machines may become not only tools and extensions of our senses, but our heroes, too.

Two of the best recent books on Apollo are Robert Poole’s Earthrise: How Man First Saw the Earth (Yale) and David Mindell’s Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight (MIT); both were supremely influential in the writing of this essay. Hannah Arendt’s thoughts on the “conquest of space” appeared in a 1963 essay entitled “The Conquest of Space and the Stature of Man,” a version of which appeared in subsequent editions of The Human Condition.