Hilo Heroes, June 14-20

By:

June 14, 2009

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, this week, to the following high-, low-, no-, and hilobrow heroes. Click here for more HiLo Hero birthdays.

The name MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE (1904-71) conjures up an image: a woman with a camera balanced atop one of the chromed, art-deco eagles that guard the upper reaches of New York’s Chrysler Building. Though she didn’t snap the shutter herself, the portrait is emblematic of both her physical courage and commitment to her art. Her photojournalism broke barriers at time when women were supposed to be shy and retiring: Bourke-White’s work inside steel factories, as the first western photographer allowed into the Soviet Union, and on the front lines of World War II demonstrated otherwise. Her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, was published in 1963; I read it in fifth grade and was inspired by her larger-than-life experiences, among them witnessing the liberation of Buchenwald, and interviewing Gandhi hours before his assassination. She survived a helicopter crash and being strafed by the Luftwaffe, succumbing at the end only to Parkinson’s disease. So when adversity strikes, I like to remind myself of Bourke-White on her precarious perch: fearless and following her dream. — Lynn Peril

The 1960s-80s comic series Corto Maltese, by Italian-born cartoonist HUGO PRATT (1927-95), was — on the surface — a 1930s-style pulp adventure that improved on Terry & The Pirates and the like through its attention to historical detail as well as lyrical writing and illustration. But Pratt’s work was deeper even than such inspirations as Robert Louis Stevenson and Jack London. As all the best cartoonists seem to do, Pratt used his erstwhile adventurer character as a way to engage with a world that often seems random and tragic: Corto Maltese, a sailor and man of action born without a fate line on his palm, is on a journey which may involve smugglers, pirates, and villains, but which at its core is an examination of the fickle nature of life. Pratt — a World War II survivor, accused spy, and resident of Africa, Europe, and South America — offers an insight into everything we hold dear in this modern world. It could all be taken away by a rogue wave. — Joe Alterio

While it’s conventional to call Oliver Hardy a “straight man,” it would be more accurate to think of the character created by British comic actor STAN LAUREL (1890- 1965) as the duo’s “curved man.” Though he may seem idiotic, perhaps Stan’s character developed as a result of knowing too much. Ollie, who insists on recognizing every category of politeness and propriety, no matter how absurd, is a fool; Stan, however, refuses ever to recognize any categories. If he can’t differentiate, for example, between male and female — he sometimes replies to an admonishing male authority figure with a meek, “Yes, ma’am” — it’s because in Stan’s world the categories “male” and “female” don’t exist. So when Stan touches his chest, ruffles his hair, and lets the hysteria run through him — or does a languid double-take at the sight of a water fountain or some other mundane object — he’s not just being silly. He’s reflecting back to us our own doubts, our epistemological and phenomenological anxieties. He’s reflecting mine, anyway. — Greg Rowland

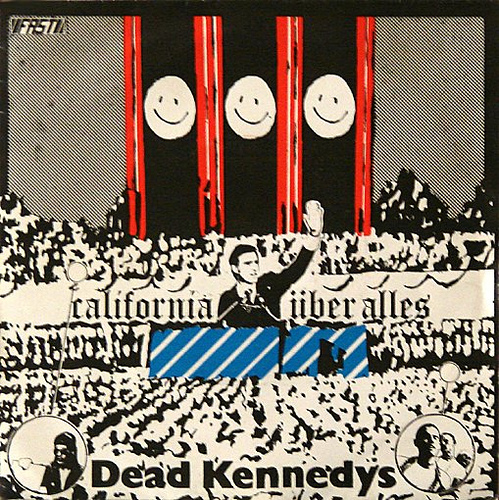

It’s never been easy to like Eric Reed Boucher, better known as JELLO BIAFRA (born 1958). In my New Jersey high school, the mainstream kids were offended the very idea of the Dead Kennedys, while the hardcore purists found them old hat. Jello himself — with his screeching voice, hatred of nostalgia, and holier-than-thou left politics — still seems like he’s defying you to embrace him. But embrace him I do: he saved my life. I vividly remember unfolding the cassette liner notes for Frankenchrist (1985) and learning I was not alone in my Reagan-era anger and despair. With lyrics like “Let kids learn communication/Instead of schools pushing competition/How about more art and theater instead of sports?… No one will do it for us/We’ll just have to fix ourselves/Honesty ain’t all that hard,” Jello knocked the scales from my teenaged eyes. — Jason Grote

Perhaps JÜRGEN HABERMAS (born 1929) is most dear to us for developing and elaborating over the course of decades an intricately woven Grand Theory founded in the notion that sincere, earnest public discussion is the basis for a well-lived life and a just, well-ordered democracy. Although its historical accuracy has been challenged, we still love Habermas’ first book for bringing into general discourse the notion of the Öffentlichkeit, or public sphere, and its importance in the development of a true deliberative democracy. Having been trained in postwar Germany, Habermas demanded that philosophy grapple with the empirical as well the theoretical. Despite the fights between their adherents during the 1980s, Habermas and Foucault found themselves much aligned in many respects: both believed that one cannot separate life from theory; both worried over the mission creep of modernity into what Habermas would call the Lifeworld. But where Foucault seemed defeated by this, Habermas remains inexhaustibly hopeful about the possibilities of real human communication. Although the café culture may be kaput, in Argonaut Follies, little magazines, fledgling websites, and vigorous bookstore debates lies the hope for the future. — Tor Aarestad

In 1965, SHIRLEY MULDOWNEY (born 1940) beat down the doors of the National Hot Rod Association and became the first licensed female drag racer. And despite the signature pink cars monogrammed with her nickname, “Cha-Cha” (which she has long since renounced: “There’s no room for bimboism in racing”), she was in no way a novelty act. She distinguished herself in the surprisingly dangerous Funny Car category, surviving fiery crashes and setting records, before moving on to win three NHRA Top Fuel championships. In the 1983 biopic, Heart Like A Wheel, Bonnie Bedelia plays the young Muldowney as a plucky housewife with a need for speed. It’s a nice movie, but I doubt it even approaches the true measure of Muldowney’s badass velocity. To look at her in this video, you might think you’d discovered the missing link between Wanda Jackson and Steve McQueen. She pulls on her boots, checks the engine, tucks away her teased black hair, and lowers herself behind the wheel of a funny car. A few seconds later you’re watching a parachute open, and you know that someone has just eaten her dust. — Mimi Lipson

Just as it isn’t Burt Bacharach’s fault that his name is now rock-critical shorthand for “This band knows someone with a flugelhorn,” BRIAN WILSON (born 1942) is not to be blamed that his is invoked every time more than two people sing together on a record, even when the results sound more like The Roches (Dirty Projectors) or The Back Porch Majority (Polyphonic Spree). Even when the familiar (and gorgeous) block harmonies he arranged for The Beach Boys are copped with some success (Grizzly Bear), the amalgam of whimsy, melancholia and sheer melodic grace — often closer in spirit to Irving Berlin or even Stephen Foster than anything comfortably categorized as rock and roll — at the core of Wilson’s best work remain elusive. Perhaps it’s only the overt auterist complexities of Pet Sounds and Smile (the unfinishable Woyzeck of popular music, its 2004 Wilson-approved live reconstruction notwithstanding) that allow us to hear the same qualities in such early, ostensibly frothier fare as “Fun, Fun, Fun.” But that doesn’t mean they aren’t there. — Franklin Bruno