The Argonaut Folly (part 2 of 3)

By:

June 10, 2009

An abridged version of this essay appeared in the journal n+1 (Winter 2007).

PART ONE | PART TWO | PART THREE

In 1878, a quarter-century after The Blithedale Romance, Friedrich Nietzsche published Human, All Too Human, a collection of aphorisms whose subtitle proclaimed it “A Book for Free Spirits.” Here, the 33-year-old Nietzsche expressed his deep concern for the flourishing of potentially exemplary individuals. Harking back to a fantasy he’d entertained when, as a stripling academic, he’d proposed to friends a “new Greek Academy” in which a revitalized western culture might be forged, throughout Human, All Too Human Nietzsche reached out to superior types disgusted by “the ochlocratic nature of superficial minds and superficial culture,” and to those “free spirits” able to overcome within themselves their “origin, environment… [and] class.” In scattered entries that read today like New York Review of Books lonelyhearts ads, Nietzsche implored “oligarchs of the spirit” to overcome “all spatial and political separation,” by living and working together somewhere in Europe.

Like Hawthorne’s Coverdale, Nietzsche admiringly described his imaginary colleagues as jailbreak artists, outsiders, crooked sticks. In Human, All Too Human, he suggests that “the prisoner’s wits, which he uses to seek means to free himself by employing each little advantage in the most calculated and exhaustive way, can teach us the tools nature sometimes uses to produce… the perfect free spirit.” And in his 1881 aphorism collection, Daybreak, he laments that those free spirits who “do not regard themselves as being bound by existing laws and customs” are everywhere “denounced as criminals, free-thinkers, immoral persons, and villains.” Elsewhere in Daybreak, Nietzsche characterizes his proposed “company of thinkers” as intrepid sailors traversing the void, as voyageurs whose ship may end up “wrecked against infinity,” and as “aeronauts of the spirit”: birds of passage on an island enjoying “a precarious minute of knowing and divining, amid joyful beating of wings and chirping with one another.” Impatiently waiting for these aeronauts and Argonauts to join him in forming a colony, he writes of them, “Is it too much to ask that they should give a sign to one another?”

Nietzsche’s lonelyhearts ads went unanswered — except by Paul Rée and Lou Salomé, who first proposed to him a non-sexual yet “trinitarian” workshop and living arrangement, then ran away together. By 1887, he had given up on his colony. In a preface to a new edition of Human, All Too Human, published that year, Nietzsche would confess with great bitterness that he had “invented for myself the ‘free spirits’ to whom this melancholy-valiant book… is dedicated.” Having become bitter about the impossibility of an Argonaut Folly, he began — in his later writings, beginning with Thus Spoke Zarathustra — to sketch out an anti-egalitarian social order organized for the benefit of an elite caste of Übermenschen, whose sole concern would be the cultivation of their own excellence. The rest of humankind would be put to work.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, modernist writers and thinkers like Thomas Mann, André Gide, William Butler Yeats, Rainer Maria Rilke, George Bernard Shaw, Eugene O’Neill, and August Strindberg responded enthusiastically to either the early, hilobrow Nietzsche’s vision of a community of uniquely talented free spirits, or to the later, anti-lowbrow Nietzsche’s vision of an aristocracy of the best and brightest, a utopia for the few and dystopia for the many.

In the 1890s, Alfred Jarry shared a house, known as “Le Phalanstère,” in the southern suburbs of Paris with Alfred Vallette, his wife Marguerite Eymery (known better under her pseudonym Rachilde), the opulently bearded André-Ferdinand Hérold, and other friends. Vallette co-founded the journal Mercure de France, in which extracts of Jarry’s great ’pataphysical adventure Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll were first published. (The book was not published until 1911, four years after Jarry’s death at the age of 34.) The communal home was named — semi-seriously and semi-mockingly — after a type of building designed for a self-contained utopian community, according to the speculations of the anarchist Charles Fourier. Fourier coined the term by combining the word phalange (phalanx, the basic military unit in ancient Greece), with monastère (monastery).

Among those fictional characters who in the early part of the 20th century would echo the later Nietzsche’s vision is Mr. Scogan, who in Aldous Huxley’s 1921 novel, Crome Yellow, defends eccentric visionaries, whom he insists should be kept “safe from public opinion, safe from poverty, leisured, not compelled to waste their time in the imbecile routines that go by the name of Honest Work.” Scogan later reveals his fantasy of a brave new world in which the visionaries will be Directing Intelligences, and in which all the imbecile routines will be performed by the hapless Herd. Herman Hesse’s 1943 novel, The Glass Bead Game, meanwhile, is set in Castalia, a scholarly enclave whose uniquely talented inhabitants dedicate themselves to a syntactic game requiring a mastery of every one of the arts and sciences. If Hesse’s fictional colony is anti-lowbrow, his protagonist is something of a hilobrow. He finally sours on Castalia not because it’s elitist, but because it’s not free-spirited.

But let’s back up, slightly, to the years of moral and intellectual crisis during and after World War I, when so many thinkers and writers lost confidence in the culture of rationality that had prevailed in the West since the Enlightenment. “How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, Europeanized, enervated?” demanded Hugo Ball in 1916. The answer to that question, not a few outsider intellectuals suggested, involved first joining forces with one’s comrades and beating a retreat.

We might take note, for example, of the Forte Circle, a network of radical pacifist intellectuals and artists — including the German anarchist Gustav Landauer, the Viennese Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, the Russian-born painter Wassily Kandinsky, the French writer Romain Rolland, and the progressive American novelist Upton Sinclair — who toyed with the notion that a community devoted to intellectual and spiritual activity might arrest the political crises of pre-World War I Europe. (In 1906, Sinclair had plowed the proceeds from The Jungle into Helicon Hall, a New Jersey commune — its name, like Hesse’s Castalia, was drawn from Greek myth — where 80 intellectuals and artists lived until it burned down in ’07.) We might also point to D.H. Lawrence, who in the winter of 1914 worked out the objectives, aims, and laws for communal life in Rananim, a colony far from England, perhaps on an island. Lawrence urged the most talented writers of his acquaintance — E.M. Forster, Bertrand Russell, a young Aldous Huxley — and England’s more daring young aristocrats to make this daydream a reality. But his friends quickly stopped listening, especially after Lawrence drunkenly vomited on himself during one memorable Rananim appeal.

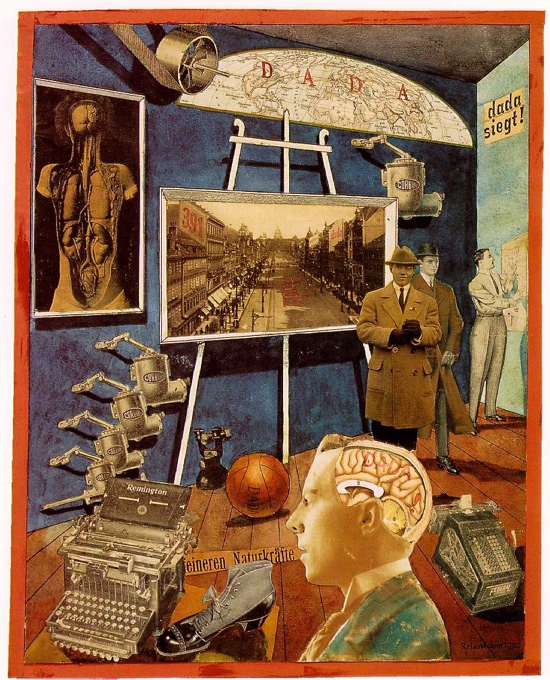

And then there’s Dada, a movement that began not in the usual sense of artists committed to a particular aesthetic credo, but as a way for displaced and fed-up outsiders to pass the time together. Located in neutral Zurich, the Cabaret Voltaire, as German founders Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings renamed their favorite bar, became a gathering point not only for Voltaire-esque freethinkers like Hans Arp (Alsace), Francis Picabia (France), and Tristan Tzara (Romania), but for pacifists, draft dodgers, revolutionaries, and iconoclasts. As Dada scholar Leah Dickerman points out, before Dada was a movement starring André Breton, Max Ernst, and Man Ray, the Cabaret Voltaire “served to foster community… [it was] a self-consciously low-tech corrective to the increasingly attenuated bonds of modern society.” Ignore its reconceptualization of art as intervention, its pioneering of montage and the readymade: Dada’s achievement lies first and foremost in its successful realization of Nietzsche’s vision of a transnational community of misfits. To gaze upon Raoul Hausmann’s 1920 collage, Dada Triumphs, which asks us to imagine Dadaists plotting world domination, is to feel the absurdist optimism of Argonauts setting off on a mission impossible.

One also thinks of Maksim Gorky’s Dom isskustv. Founded by Gorky and Kornei Chukovsky in 1919, the Petrograd House of Arts (a once-lavish private home on the Nevsky Prospekt) housed as many as 56 poets, novelists, critics, and artists at one time — including Marietta Shaginian, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Nikolai Tikhonov, Elizaveta Polonskaia, and the formalist critic Viktor Shklovsky. This was during a period of great social and political turbulence. Gorky had been active in the Marxist communist and later in the Bolshevik movement, and for a time associated himself with Lenin and Bogdanov’s Bolshevik wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. However, in 1918 Gorky published a collection of essays critical of the Bolsheviks; Untimely Thoughts denounced Lenin as a tyrant for his senseless arrests and repression of free discourse. In 1921 Gorky left Russia for Berlin, and disbanded the House of Arts.

Next stop: Breton’s first Manifesto of Surrealism, published in 1924. Breton was concerned with what has elsewhere been called the invisible prison of daily life, the legitimating discourse of which we’re trained to think of as common sense. Who can escape such a prison and embark on new adventures? Perhaps only the insane, writes Breton: “Christopher Columbus should have set out to discover America with a boatload of madmen.” Breton then describes just such a ship of foolish Argonauts: “For today I think of a castle, half of which is not necessarily in ruins; this castle belongs to me, I picture it in a rustic setting, not far from Paris,” he writes. “A few of my friends are living here as permanent guests: There is Louis Aragon leaving; he only has time enough to say hello; Philippe Soupault gets up with the stars, and Paul Eluard, our great Eluard, has not yet come home. There are Robert Desnos and Roger Vitrac out on the grounds poring over an ancient edict on dueling… there is T. Fraenkel waving to us from his captive balloon,” and so forth. Sadly, though not unexpectedly, in a 1929 Preface for a Reprint of the Manifesto, we find Breton describing his vision as “something that, no matter how bravely it may have been, can no longer be.”

Still, during the 1930s and early ’40s, thinkers and artists continued to band together for Argonaut-ish purposes. Think of the re-launching of Partisan Review in ’37 as a journal whose editors — including Philip Rahv and Dwight Macdonald — adhered to the ideal of the luftmensch. (This Argo soon foundered on the rocks of the postwar liberal consensus; Macdonald jumped ship.) Think too of the cadres of writers and artists (Hemingway, Malraux, Dos Passos, Orwell, Buñuel, Miró) who banded together on behalf of the Republican cause in Spain; or Georges Bataille’s anti-fascist journals/organizations Contre-attaque, Acéphale, and College of Sociology; or the efforts of Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse, and the rest of the Frankfurt School-in-exile to analyze the infinitely subtle workings of late capitalism from New York and Los Angeles. There’s also Black Mountain, the experimental college in North Carolina where, from 1933-56, talented misfits like John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Buckminster Fuller, Charles Olson, and Paul Goodman rubbed elbows. Think, too, of the Brooklyn townhouse inhabited in ’40-41 by W.H. Auden, Carson McCullers, Paul and Jane Bowles, and Gypsy Rose Lee. At the core of each of these endeavors, the animating spirit of the Argonaut Folly can be detected.

PART ONE | PART TWO | PART THREE

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE