The Argonaut Folly (part 1 of 3)

By:

June 10, 2009

An abridged version of this essay appeared in the journal n+1 (Winter 2007).

PART ONE | PART TWO | PART THREE

I set out to commemorate the heroes of old who sailed the good ship Argo … in quest of the Golden Fleece. Muses, inspire my lay.

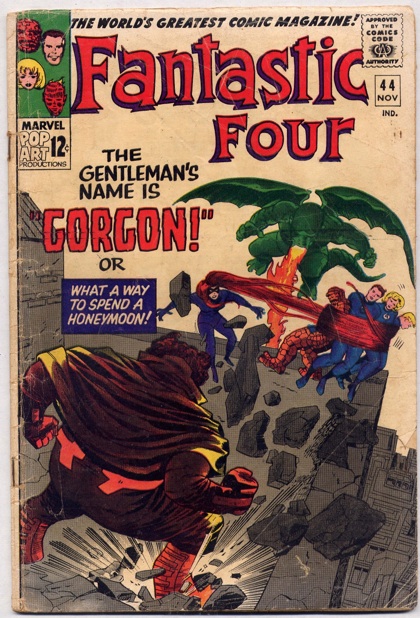

ONCE UPON A TIME, according to Apollonius of Rhodes (and before him Homer, Hesiod, Pindar, and countless forgotten mythopoets), a Greek prince named Jason was sent by his uncle, a usurper, to parts unknown on a mission impossible: to fetch a magical golden ram’s fleece. Jason commissioned a 50-oared galley, the Argo, and manned it with the noblest heroes of the era. Their number included mighty Heracles; the bard Orpheus, whose voice enchanted nature itself; bronco-busting Castor and his immortal brother, the boxer Polydeuces; Zetes and Calaïs, the winged sons of the North Wind; as well as the seer Idmon, the sign-reader Mopsus, fleet-footed Euphemus, eagle-eyed Lynceus, shape-shifting Periclymenus, and Aethalides the mnemonist. After adventures on one perilous island after another, and having safely navigated the Clashing Rocks guarding the entrance to the Black Sea, the surviving Argonauts arrived at Colchis (Georgia), acquired the fleece with the aid of the witch Medea, and made their way back home.

That, at any rate, is what we learn from children’s books of mythology. But a wised-up reading of the Argonautica of Apollonius suggests that Jason’s crew of ultra-talented specialists was less a ship of heroes than a Narrenschiff, a ship of fools. Or rather: a ship of heroes is always already a ship of fools. At which juncture I will crib from Ruskin by stating that if, at any point of this inquiry, I should interfere with any of the reader’s previously formed conceptions, and use the term “Argonaut” in any sense which he would not willingly attach to it, I do not ask him to accept, but only to examine and understand, my interpretation, as necessary to the intelligibility of what follows.

Take Jason, for example. Except when under the influence of Medea’s pharmaceuticals he’s more of a dandy and a cocksman than a warrior; and for someone we’ve been taught to think of as an inspiring leader, he spends an inordinate amount of time “obsessed by fears and intolerable anxiety,” as he puts it in the Argonautica, and lamenting that all is lost. As for the rest of the crew, they are not only fiercely competitive but a violently quarrelsome lot. Famously prone to fits of drunken rage after which those close to him turn up dead, Heracles is accidentally marooned by the helmsman, Tiphys; when Telamon accuses Tiphys of doing it on purpose, a cynical reader can’t help but agree. And it’s not a little suspicious that overweening Idas, having threatened Jason’s loyal supporter Idmon, should be one of the only witnesses when Idmon is slain by a boar. Later, Idas will off Castor in a dispute over cattle and Polydeuces will snuff Idas’ brother, Lynceus; later still, Heracles will massacre Zetes and Calaïs. To be an Argonaut, then, is to be a member of an outfit that is, to say the least, agonistic.

But in what sense can the Argonauts be called foolish? They are fools for precisely the same reason that they are heroes: because each one of them is superior to ordinary mortals in an overly specialized fashion. When they’re in their rightful element — council, banquet table, or boudoir, in Jason’s case; in Heracles’, the battlefield — there is no stopping them. But in every other circumstance the Argonauts are, as Apollonius frequently notes, amechanos: without resource. Jason is all talk, no action; Heracles is all brawn, no brain. When Tiphys dies (after a mysterious illness that, frankly, bears investigation), Jason collapses on the beach, lamenting, “We are doomed to grow old here, inglorious and obscure”; and when Heracles breaks his oar he sits speechless and glaring: “He was not used to idle hands.” It proves all too easy for these intrepid birds of passage to become as helpless as Baudelaire’s albatross, whose enormous wings make him monarch of the air but a risible cripple on earth. No wonder that Heracles grumbles about how they seem more like exiled criminals than heroes: to be an Argonaut is to be a superman viewed by ordinary mortals as a misfit, a loser, an outlaw.

It first occurred to me to read the Golden Fleece myth against the grain half a dozen years ago, around the time that Hermenaut, an independent journal whose title was not uninfluenced by Greek myth, and which I’d spent the 1990s editing and publishing, was foundering. A journal published without the sponsorship of a foundation or university, and also without the benefit of a trust fund or a sugar daddy, is a ship plowing uncharted waters without compass or anchor: each new issue is an uncharted island harboring exotic dangers and delights, while the twin hazards of distribution and ad sales typically prove as impassable as the Clashing Rocks. The editors of such journals can only console themselves that their masthead and contributor list will one day be regarded as rosters of the best and brightest talents of the era. But in decades past, certain writers, thinkers, and artists have taken off on even more ambitious flights of fancy. For such dreamers, merely collaborating with peers who possess skills as unique and impressive as they know their own to be isn’t good enough. Like the Argonauts, they want nothing less than to live and strive together, each and every day.

I call this dangerously alluring fantasy the Argonaut Folly.

I myself fell prey to an Argonaut Folly in 1989, while taking time off from college. I was 21, and living in the still mostly un-gentrified Boston neighborhood where I’d grown up, in the Egleston Square neighborhood on the border of Jamaica Plain and Roxbury. The elevated train along Washington Street had recently come down, revealing to my eyes, as though for the first time, the disused former Franklin Brewery. I dreamed of moving into the building along with the most visionary and talented young men and women of my acquaintance. Living and working in our massive brick habitat, which would (I fantasized) encompass apartments, offices and studio spaces; a public restaurant and a private nightclub; a collective library of books, journals, and records; and eventually a school and rooftop playground for our children, we would form a freewheeling, democratic research seminar whose findings would change… everything. But communes had gone out of fashion, by then. So I went back to school.

In 1992, around the time that I was dropping out of a master’s program at BU, I launched Hermenaut as a photocopied zine. Scott Hamrah, who soon became the zine’s coeditor, and I published a new issue whenever I’d saved up enough money from one of the many jobs I held during those years. In the latter part of the Nineties, I went to work for an Internet start-up. When it was acquired by a publicly traded company, I immediately cashed in my options (less than $100,000, but a fortune to me), borrowed more from friends and family, and rented a tiny office in the former Haffenreffer Brewery, just down the street from the Franklin Brewery building. I spent every day there, working shoulder to shoulder — editing and publishing what had become a journal, and a website — with a dissensual, agonistic group of talented peers. Could my youthful vision of an Argonaut Folly, I sometimes wondered, be far from realization?

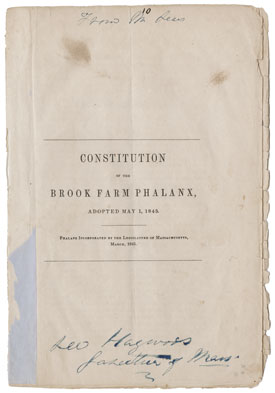

After a couple of heady years, however, Hermenaut went broke. So did I. Unable to afford a house in my own rapidly gentrifying neighborhood, I moved with my pregnant wife, our toddler son, and a heavy load of unsold magazines and credit-card debt to West Roxbury. This sleepy Boston neighborhood’s one claim to fame, I was soon reminded, is Brook Farm, New England’s first secular utopian community, which failed after transforming itself into a Phalanx modeled upon the anarchistic theories of the French social scientist Charles Fourier. Readers, I could relate all too well to Brook Farm’s failure! That’s why our tour begins there.

In 1841, Brook Farm co-founder George Ripley announced that the object of the colony was “to guarantee the highest mental freedom, by providing all with labor, adapted to their tastes and talents, and securing to them the fruits of their industry… and thus to prepare a society of liberal, intelligent, and cultivated persons [leading] a more simple and wholesome life, than can be led amidst the pressure of our competitive institutions.” After failing in ’47, Brook Farm would be remembered as little more than a bucolic retreat for abolitionists, Transcendentalists, and other progressive Bostonians. But here in the 21st century, when even leftists warn that utopian schemes lead to oppression and mass murder, its reputation may be worsening: a 2004 revisionist history of the experiment was subtitled The Dark Side of Utopia. The author of that book takes his cue in part from Ripley’s friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, who declined an offer to join the colony. Writing in the Dial in 1841, Emerson criticized Fourierism for regarding man as a mutable thing to be “ripened or retarded” at the will of the system. What utopians overlooked, insisted the arch individualist, was the “faculty of Life, which spawns and scorns system-makers.” Every utopia is a dystopia, claimed America’s first anti-utopianist.

But although Brook Farm had its downsides, I’d argue that its failure was a success — because it spawned, in American literature, our first Argonaut Folly. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1852 novel, The Blithedale Romance, is a treatise on the failings of thoroughgoing social reform disguised as a novel set in a West Roxbury utopian colony. In ’41, the 37-year-old Hawthorne was casting about for a place where he would have the leisure and energy to concentrate on his writing. Invited to join Brook Farm, he quit his position in the Boston customhouse and became one of Brook Farm’s founding members; but a few months later, he moved out. Scholars have tended to describe the fictional colony of Blithedale as a dystopia, and Hawthorne as an anti-utopian predecessor to the likes of Zamyatin, Huxley, or Orwell. Certainly, Hawthorne had little sympathy for utopian notions: Coverdale, the semi-autobiographical narrator of Blithedale, reflects ruefully on “our exploded scheme for beginning the life of Paradise anew,” while Zenobia, a character who may have been inspired by Margaret Fuller, laments what she calls the colony’s “effort to establish the one true system.” But read between the lines of Hawthorne’s text and we discover what Fredric Jameson calls “anti-anti-utopianism”: an effort to free the imagination from the paralyzing spell of the quotidian without falling into the error of totalitarianism.

“On the whole, it was a society such as has seldom met together; nor, perhaps, could it reasonably be expected to hold together long,” Hawthorne has Coverdale recount of Blithedale. “Persons of marked individuality — crooked sticks, as some of us might be called — are not exactly the easiest to bind up into a fagot,” he goes on to explain. One feels compelled to remind readers about the etymology of the term fascism, and to suggest that Coverdale’s apparently negative comment about Blithedale’s failings can be read positively. But do these crooked sticks, these Emersonian individualists, have anything at all in common? Just one thing, according to Coverdale: each of them possesses sufficient lucidity and strength of character to discern and escape from what has been called the invisible prison of everyday life under capitalism. “We had left the rusty iron frame-work of society behind us,” exults Coverdale. “We had broken through many hindrances that are powerful enough to keep most people on the weary tread-mill of the established system, even while they feel its irksomeness almost as intolerable as we did.” Not noble, saintly utopians, then, but cranks and idlers: these are Hawthorne’s heroes.

Unanimity of purpose was never enforced at Brook Farm, we learn even from the new revisionist history of the colony; nor was it at the fictional Blithedale. (Hawthorne quit his labors at Brook Farm not because he was an individualist rebelling against repressive groupthink, but because he soon discovered, as he has Coverdale put it, that “intellectual activity is incompatible with any large amount of bodily exercise.”) In fact, Hawthorne’s Blithedale fails because the colony’s founding members cannot finally agree on the point of the experiment: Hollingsworth is entirely consumed with his own philanthropic theory; Zenobia’s overweening cause is women’s rights; Coverdale is an aesthete and intellectual. “Our bond, it seems to me,” the narrator muses, “was not affirmative, but negative. We had individually found one thing or another to quarrel with in our past life, and were pretty well agreed as to the inexpediency of lumbering along with the old system any further. As to what should be substituted, there was much less unanimity.”

Again, we can read Hawthorne’s negativity as an affirmation. An agonistic, dissensual community whose members reject any kind of overarching ideology may be a lousy model for what we usually think of as a utopian social order. But for precisely that reason, it’s the only kind of intentional community that Hawthorne could have joined. In his preface to Blithedale, he goes out of his way to make clear that he is no anti-utopian, confessing that the author had “ventured to make free with his old and affectionately remembered home at Brook Farm, as being certainly the most romantic episode of his own life.” For aspiring Argonauts, Blithedale is indeed an inspiring romance. So, for that matter, is the rewritten myth that Hawthorne would publish the very next year, in Tanglewood Tales: “The Golden Fleece.”

PART ONE | PART TWO | PART THREE

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE