My Wes Anderson Problem — And Ours

By:

May 21, 2009

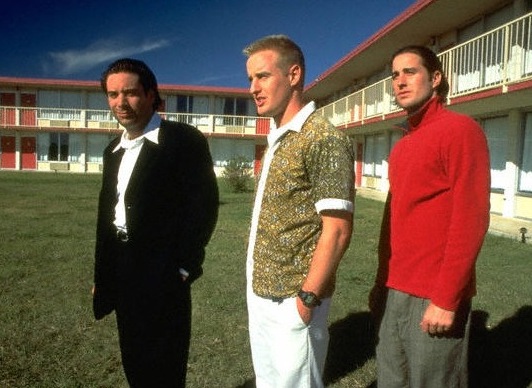

WES ANDERSON’S Bottle Rocket (1996) raised the hopes of hilobrows everywhere, and his Rushmore (1998) fulfilled those hopes in spades. So what happened?

Anderson once knew how to get a great performance out of his actors. In Bottle Rocket, Luke Wilson wasn’t yet the stiff romantic foil he’s since become; or, to be more precise, his stiffness was charming, anti-actorly somehow — like Nicolas Cage and Matt Dillon used to be, too. Owen Wilson was truly extraordinary: the actor’s lazy yet determined unwillingness to do anything but play himself seemed tailormade for his idealistic-eccentric slacker role. Rushmore introduced us to Jason Schwartzman, who’s never been as good since he lost the braces and glasses; and to a soulfully lame Bill Murray whose existence nobody but Anderson (with the possible exception of Tim Burton) suspected. When Luke and Andrew Wilson (not to mention Kumar Pallana) reappeared in Rushmore, and Owen’s name appeared again as co-writer, we thought: Wow! Anderson, like Ed Wood or Orson Welles or Martin Scorsese (or Tim Burton, again — has anyone ever compared the two?), has a troupe! Scorsese himself named Anderson the next Scorsese.

In those first movies, Anderson’s penchant for precisely correct props, stylishly unstylish costumes, bleak settings rendered exquisite through the use of primary colors and neo-autistic symmetries, and cherry-picked pop songs sparkling against an ambient setting crafted by the great Mark Mothersbaugh, was received by this moviegoer as nothing less than an antidote to that year’s supposedly thrilling low-middlebrow actioners (Independence Day, Mission: Impossible), supposedly charming mainstream Hollywood fare (Jerry Maguire, Swingers), and shamesplotation disguised as supposedly smart high-middlebrow indies (Welcome to the Dollhouse).* Anderson’s movies were mostly hailed as charming, but they were also thrilling (the botched robbery at the end of Bottle Rocket, Max’s attempts to revenge himself on Blume in Rushmore), and — yes — smart. Rushmore was a far more penetrating examination of the dandy-as-artist than, for example, that same year’s Velvet Goldmine.

I didn’t ever want Rushmore to end. Despite a few standout performances, though, I couldn’t wait to see the last of The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, and The Darjeeling Limited. I know! I know! I’m hardly alone in deploring Anderson’s slide from style to shtick; Steely Dan, for example, has openly stated its collective preference for the director’s early work to his twee trilogy of family dysfunction and cool vintage suitcases. But the problem has metastasized!

As Elbert Ventura (a Zetan?) reported in Slate today, Anderson’s now-regressive shtick (“poker-face eccentricity, affection for the oddball, fastidiously arranged clutter, an affinity for the precocious and childlike”) has spread like a virus from American indie cinema — Ventura calls Juno, Napoleon Dynamite, Son of Rambow, Charlie Bartlett, and Garden State an “Andersonian quirkfest” — to TV shows (Flight of the Conchords), music videos (Vampire Weekend’s “Oxford Comma,” the Decemberists’ “16 Military Wives”), and commercials (see below).

Friends, we must study the qualitative differences between Anderson’s first two and last three movies, in order to reverse-engineer Middlebrow’s sinister method of quatsch-ification. Exactly what happened to Anderson’s style? What rough edges were smoothed, what happy accidents routinized, what uncanny moments rendered all too canny? How were Anderson’s dynamically opposed childish and adult sensibilities synthesized into the merely grownup? Answer these questions soon, so you’ll be critically armed in time for his forthcoming adaptation of Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox.

Anderson has been quirked around, hilobrows. Don’t let it happen to you.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).

* No disrespect intended to 1996’s actually thrilling movies like Broken Arrow and Fargo, and actually smart indies like I Shot Andy Warhol and Big Night.