Houdini’s Lament

By:

February 27, 2009

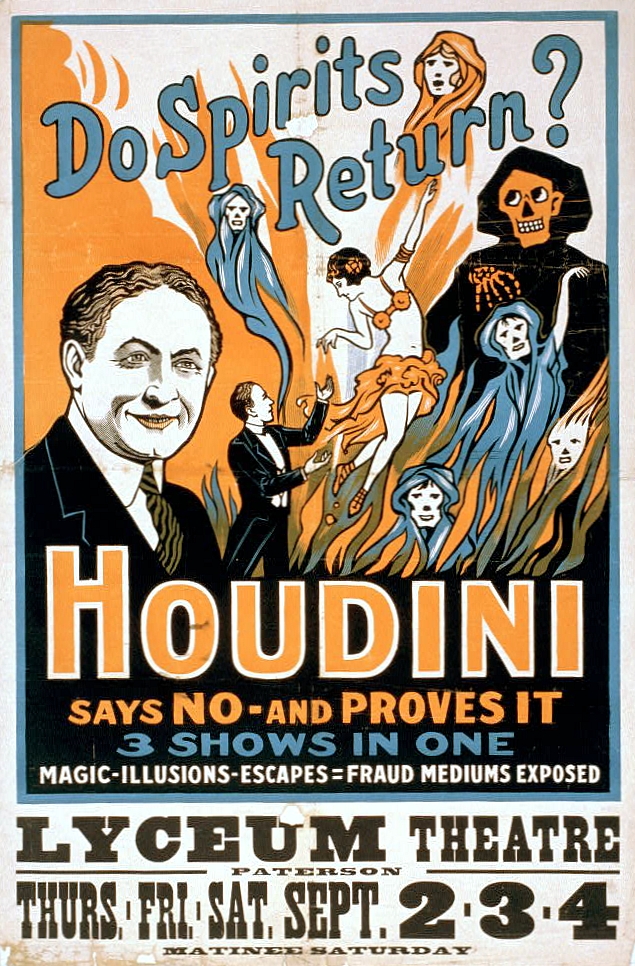

Harry Houdini was not only the storied illusionist of memory; in his time he was famous as a debunker of mediums and psychics and as a prolific author as well. In his book The Miracle-Mongers and Their Methods, Houdini explored the tricks and secrets of fire artists, strongmen, and freaks.

Much has been written about the feats of miracle-mongers, and not a little in the way of explaining them. Chaucer was by no means the first to turn shrewd eyes upon wonder- workers and show the clay feet of these popular idols. And since his time innumerable marvels, held to be supernatural, have been exposed for the tricks they were. Yet to-day, if a mystifier lack the ingenuity to invent a new and startling stunt, he can safely fall back upon a trick that has been the favorite of pressagents the world over in all ages. He can imitate the Hindoo fakir who, having thrown a rope high into the air, has a boy climb it until he is lost to view. He can even have the feat photographed. The camera will click; nothing will appear on the developed film; and this, the performer will glibly explain, proves” that the whole company of onlookers was hypnotized! And he can be certain of a very profitable following to defend and advertise him.

So I do not feel that I need to apologize for adding another volume to the shelves of works dealing with the marvels of the miracle- mongers. My business has given me an intimate knowledge of stage illusions, together with many years of experience among show people of all types. My familiarity with the former, and what I have learned of the psychology of the latter, has placed me at a certain advantage in uncovering the natural explanation of feats that to the ignorant have seemed supernatural. And even if my readers are too well informed to be interested in my descriptions of the methods of the various performers who have seemed to me worthy of attention in these pages, I hope they will find some amusement in following the fortunes and misfortunes of all manner of strange folk who once bewildered the wise men of their day. If I have accomplished that much, I shall feel amply repaid for my labor.

Later in Miracle Mongers, Houdini argues that fire conjurers and other magic-makers — those who are true artists, and not merely on the make — suffer no damage to their practice if their secrets are exposed.

THE yellow thread of exposure seems to be inextricably woven into all fabrics whose strength is secrecy, and experience proves that it is much easier to become fireproof than to become exposure proof. It is still an open question, however, as to what extent exposure really injures a performer. Exposure of the secrets of the fire-eaters, for instance, dates back almost to the beginning of the art itself. The priests were exposed, Richardson was exposed, Powell was exposed and so on down the line; but the business continued to prosper, the really clever performers drew quite fashionable audiences for a long time, and it was probably the demand for a higher form of entertainment, resulting from a refinement of the public taste, rather than the result of the many exposures, that finally relegated the Fire- eaters to the haunts of the proletariat.

How the early priests came into possession of these secrets does not appear, and if there were ever any records of this kind the Church would hardly allow them to become public. That they used practically the same system which has been adopted by all their followers is amply proved by the fact that after trial by ordeal had been abolished Albertus Magnus, De Mirabilibus Mundi, at the end of his book De Secretis Mulierum, Amstelod, 1702, made public the underlying principles of heat-resistance; namely, the use of certain compounds which render the exposed parts to a more or less extent impervious to heat. Many different formulas have been discovered which accomplish the purpose, but the principle remains unchanged. The formula set down by Albertus Magnus was probably the first ever made public…

At the end, however, Houdini laments the passing of the dime museums in which the last of these artisans practiced their craft, predicting the end of the intimate illusionist in a time of media sensation and disenchantment.

Strong people, whether tricksters or genuine athletes, or both, we shall probably have always with us. But with the gradual refinement of the public taste, the demand for such exhibitions as fire-eating, sword-swallowing, glass-chewing, and the whole répertoire of the so-called Human Ostrich, steadily declined, and I recall only one engagement of a performer of this type at a first-class theater in this country during the present generation, and that date was not played.

There was still a considerable demand for these people in the dime museums, until the enormous increase in the number of such houses created a demand for freaks that was far in excess of the supply, and many houses were obliged to close because no freaks were obtainable, even at the enormous increase in salaries then in vogue. The small price of admission, and the fact that feature curios like Laloo or the Tocci Twins drew down seven or eight hundred dollars a week, show that these houses catered to a multitude of people; and not a few of the leading managers of to-day’s vaudeville, owe their start in life to the dime museum….

The dime museum is but a memory now, and in three generations it will, in all probability, be utterly forgotten. A few of the acts had sufficient intrinsic worth to follow the managers into vaudeville, but these have no part in this chronicle, which has been written rather to commemorate some forms of entertainment over which oblivion threatens to stretch her darkening wings.

Houdini’s lament reminds us of the warning sounded by his contemporary James Frazer at the end of The Golden Bough, his monumental study of the primeval source of interwoven strands of tale, riddle, and superstition in Western culture. In the end, he recognizes that science has made his discoveries possible. And yet as Houdini seemed to learn in his own troubled advocacy of reason, the pursuit of “truth” may not satisfy:

Greater things will come of that pursuit, though we may not enjoy them. Brighter stars will rise on some voyager of the future — some great Ulysses of the realms of thought — than shine on us. The dreams of magic may one day be the waking realities of science. But a dark shadow

lies athwart the far end of this fair prospect. For however vast the increase of knowledge and of power which the future may have in store for man, he can scarcely hope to stay the sweep of those great forces which seem to be making silently but relentlessly for the destruction of all this starry universe in which our earth swims as a speck or mote…. Yet the philosopher who trembles at the idea of such distant catastrophes may console himself by reflecting that these gloomy apprehensions … are only part of that unsubstantial world which thought has conjured up out of the void…. They, like much so much that to common eyes seems solid, may melt into air, into thin air.