We are Iron Man!

By:

February 24, 2009

WHO IS IRON MAN?

In the final seconds of the latest trailer for Iron Man, which stars Robert Downey Jr. and opens soon in a theater near you, the movie’s armored protagonist dodges a shell fired by a Taliban-esque tank, launches a wrist rocket, then stalks away without bothering to watch the fireworks. The musical soundtrack to this awesome heavy-metal spectacle? Naturally, it’s the instantly recognizable guitar riff and thundering bass drum intro from Black Sabbath’s anthem, “Iron Man.”

Marvel Comics introduced Tony Stark in the March 1963 issue of Tales of Suspense. Stark is a brilliant, wealthy inventor of high-tech weaponry who, while doing some field testing with US military advisers in South Vietnam, gets critically wounded by a booby-trap and is forced into the service of Wong-Chu, a “red guerrilla tyrant.” Making do with low-tech materials, and with the help of a captured Vietnamese physicist, Stark inters himself in a gadget-laden suit of iron armor whose electrified chestplate keeps his shrapnel-damaged heart beating.

Barely able to operate his new legs, Stark nevertheless confronts his nemesis: “Have you never seen an iron man before?” he taunts. Wong-Chu (a stand-in for Ho Chi Minh, not to mention the Viet Minh insurgency in South Vietnam generally) stammers, “You — you are not human! You are machine!” Pow! The “metallic hulk who once was Anthony Stark,” as the comic’s scriptwriter, Larry Lieber, has Stark put it in the origin story’s final panel, knocks Asian communism for a loop.

In 1968, the year that Marvel’s Iron Man finally got his own comic book, the US Department of Defense announced that some 24,000 troops would be sent back to Vietnam for involuntary second terms. That same year, Steppenwolf’s hit song “Born to Be Wild” introduced rock fans to the phrase “heavy metal.” Two years later, the trailblazing British heavy metal act Black Sabbath unleashed “Iron Man” — a six-minute-long rock opera about an unfortunate soul who was “turned to steel” while singlehandedly attempting to alter the disastrous “future of mankind” — on the world.

The song’s title was suggested by frontman Ozzy Osbourne; it was written by Sabbath bassist/lyricist Geezer Butler, who tended to draw heavily upon “his fascination with religion, science fiction, fantasy and horror, and musings on the darker side of human nature that posed a constant threat of global annihilation,” according to Wikipedia.

Despite getting little airplay, Sabbath’s antiwar album Paranoid reached No. 1 in England, and No. 12 in the United States. “Iron Man,” the album’s fourth track, is hailed today as one of the greatest and most influential heavy metal tunes of all time. So… does the song have something to do with the superhero?

Many metalheads claim that it does; others insist that it doesn’t. For example, see the user-generated content at the website Songfacts: “Do you want to know what this song is really about? It’s about Iron Man… as in the comic book character… get the very first issue… the parallels are obvious.” — Eric, Rockford, IL. vs. “The comic Iron Man is a super hero. The song is about a guy that ends up killing the human race because they don’t listen to him or help him after he sees the end of the world and is turned to iron. Listen to the damn song!!!” — Chris, Sacramento, CA.

My own theory is that Black Sabbath’s enduringly awesome song is a mashup of at least two sources: one is highbrow, the other lowbrow. The song’s awesomeness, in other words, is a product of its hilobrow inspiration.

LOWBROW

Theme from the 1990s “Iron Man” cartoon

I know you have doubts, readers. Go ahead and ask your questions.

Q: Was the Sabbath song inspired by the comic book? A: Marvel Comics would certainly like us to think so. For the past decade and a half at least, they’ve been hinting that when Ozzy growls, “I AM IRON MAN!” at the beginning of the song, he’s ventriloquizing Tony Stark.

For example: While the theme to the 1966-67 Iron Man TV cartoon was oddly upbeat for a show about a handicapped victim of the US military action in Vietnam (“Tony Stark makes you feel/he’s a cool exec with a heart of steel”), the theme song of the 1994-96 cartoon repeats Ozzy’s phrase (“I AM IRON MAN!”) over and over again. Although the cheesy electric guitar stylings of the latter theme aren’t much like the Sabbath song, the impressionable young viewer is supposed to connect the dots between Iron Man, the superhero, and “Iron Man,” the song.

Theme from the 1960s “Iron Man” cartoon

As I’ve already mentioned, the new Iron Man movie features the actual Black Sabbath song — along with a dozen other heavy metal classics — on its soundtrack. (In a time-warping twist, readers of The Invincible Iron Man: Extremis, a 2005-06 reboot of the comic, were told that Stark received his wound during the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan — and that the inspiration for the armor came from his favorite Sabbath song.)

Q: OK, so Marvel Comics has tried assiduously for years to establish a subconscious association between their character and the greatest heavy metal song ever. But are there any textual clues in the song itself? A: By my count, there are at least three.

1. In the song, the couplet “Can he walk at all/Or if he moves will he fall” might refer to the moment in Iron Man’s origin story where Stark falls upon first donning his armor.

2. The sing-song, childish lyrics remind us of Wong-Chu’s pidgin English.

3. The final verse — “Heavy boots of lead/Fills his victims full of dread/Running as fast as they can/Iron Man lives again!” reminds us of the teaser from Iron Man’s origin story: “Watch his awesome approach! Listen to his ponderous footsteps as he lumbers closer… closer…. For today you are destined to encounter — the invincible Iron Man!”

Q: Were British rockers in the late 1960s reading American superhero comics? A: Yes. One thinks immediately of Donovan singing about Green Lantern in his chart-topping “Sunshine Superman,” for example; and also of the fraught use of the comic book Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen in the Beatles’ movie, Help!. The comics can be spotted atop Paul’s moviehouse organ, propped up where the sheet music ought to be.

Q: Yeah, but these are DC comics. Were British rockers into Marvel? A: Yes. On Wings’ 1975 album, Venus and Mars, Paul sings a silly love song that features the X-Men’s enemy, Magneto, as well as not one but two of Iron Man’s armor-clad opponents: Titanium Man and the Crimson Dynamo.

Q: OK, but was Iron Man — the superhero — popular in England in the late 1960s? A: Yes. Here’s the cover of a book I picked up in Brighton (England) earlier this year:

Q: Iron Man is a science fiction comic. Were British rockers into science fiction? A: David Bowie.

Q: OK, but was Geezer into science fiction? A: A 1997 album by Geezer Butler’s band G/Z/R contains a Geezer-penned song titled “Among the Cybermen.” In an interview, Butler said, “The original chorus was ‘Doctor Who lies dead among the Cybermen.’ [It’s] about the final battle of Dr. Who, but was supposed to be symbolic of the end of childhood. I changed it because I thought it sounded a bit silly. Most of the album is about growing up in the era of Sixties television, and its influence on me.”

Q: OK, but was Geezer into comic books? G/Z/R’s debut album, Plastic Planet, features the song “Detective 27,” which is about Batman; Detective Comics #27 was Batman’s first appearance.

Q: OK, but did British rockers dig science fiction about iron men? A: See below.

INTERLUDE

Spend enough time on heavy metal message boards and you’ll encounter all sorts of metaphorical interpretations of Sabbath’s “Iron Man.” It’s about Jesus (in order to save mankind, the word became flesh/a man’s flesh turned to steel); it’s about blue-collar labor in a postindustrial society. It’s a Frankenstein parable about the irrational rage that follows social rejection. It’s about a high-school kid who gets bullied and snaps; it’s about a drug user who slips into a comatose state; it’s about a ghost; it’s about a soldier who returns from Vietnam with PTSD only to be reviled by American peaceniks. It’s a retelling of a legend about cursed armor that a knight can’t remove; or it’s about the invincible Green Knight that Sir Gawain fights. It’s a Weberian parable about the iron cage of capitalism. One Brainiac reader suggested: “Tony Iommi — the great guitarist in Sabbath — lost the tips of two fingers in a steel factory accident. He then had to play the guitar with metal finger caps (which added to his distinctive tone). Is Tony Iommi in fact the Iron Man? Given that Sabbath grew up and worked in the highly industrial Midlands, the song could also just be a reflection of the steel works and foundries where they came from.”

If Geezer was a science fiction fan, mightn’t the song be influenced by a sci-fi movie? In The Day the Earth Stood Still, for example, an inscrutable metal robot threatens to destroy the Earth if we don’t change our violent ways. Paul Wegener’s 1920 silent horror film, Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam), gives us a giant clay creature whose mission is to protect the Jews of Prague; instead, the creature rebels and wreaks deadly havoc. Premiere Magazine’s film critic Glenn Kenny suggests that the song reminds him of Herschell Gordon Lewis’s 1965 movie, Monster A-Go-Go, in which a returning-from-space astronaut appears to have mutated into a large, radioactive, humanoid monster.

Sure — there were other lowbrow influences, maybe. Though none so important as the comic book, as I’ve already argued… and as I’ll demonstrate conclusively after we take a look at the song’s highbrow influence.

HIGHBROW

It has been suggested by some metalhead exegetes that Geezer’s primary inspiration for “Iron Man” was a 1968 British children’s book by Ted Hughes. Now, this is a promising angle! After all, when James Parker wrote about Hughes for the Boston Globe’s Ideas section in 2003, he said:

To read Ted Hughes as a young person was pure heavy metal. The humped strength of his lines, the brain-jamming immediacy of his images, the darkness of his concerns: There was nothing else like it.

Hughes’s The Iron Man: A Children’s Story in Five Nights (published in the US, to avoid confusion with the superhero, as The Iron Giant) concerns a metallic giant who arrives in England out of nowhere. The Iron Giant, a 1999 animated film, is loosely based on the Hughes book; so is a 1989 Pete Townshend rock opera.

The Sabbath couplet “Can he walk at all/Or if he moves will he fall” springs to mind when one reads the story’s first installment, “The Coming of the Iron Giant.”

He swayed forward on the brink of the high cliff. And his right foot, his enormous right foot, lifted — up, out, into space, and the Iron Giant stepped forward, off the cliff, into nothingness. CRRRAAAASSSSSSH!

“Can he see or is he blind?” Having been smashed to bits, the Iron Giant cannot reassemble itself until its hand locates its eye. See below:

The Iron Giant is buried alive by farmers, because he’s been destroying their property. He’s tempted into the trap by a farmer’s son, Hogarth. See below:

Hogarth repents of his role in the scheme, and when the Iron Giant digs himself out of the grave, Hogarth leads him to a junkyard, where he can live peacefully. Later, the Iron Giant saves the planet from a “black flying horror,” an immense “space-bat-angel-dragon” that demands to be fed living creatures. Turns out that the alien is actually a “star-spirit,” who normally sings — thus helping to create the music of the spheres. But “listening to the battle shouts and the war cries of the earth — I got excited; I wanted to join in.” Having defeated the star-spirit in a contest, the Iron Giant commands him to fly around the earth, singing, every night. This has a wonderful effect: “The singing got inside everybody and made them as peaceful as starry space and blissfully above their earlier little squabbles.” World peace ensues.

Why did Hughes write the book? He later said that he wanted to comfort his children after the suicide of their mother, Sylvia Plath. Hughes described The Iron Man as an “imaginative strategy for dealing with neurosis” — that is to say, he wanted to tell children a story in which the horrors of the adult world (war, runaway technology, environmental disaster) can be mastered thanks to a child’s natural wisdom.

Q: We’ve established that Geezer, like other British rockers of the late ’60s, was a fan of lowbrow sci-fi and American superhero comics. But were British rockers of the period into highbrow children’s fantasy literature? A: Yes. John Lennon aped Lewis Carroll; Pink Floyd named their first album after a chapter of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows; and Led Zeppelin laced their lyrics with references to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. True, Hughes’s book wasn’t a time-honored classic, in 1968, but the timing of its publication is spot-on.

Many plot details of Sabbath’s “Iron Man” look like references to the comic book. I’ve already made note of a couple of “Iron Man” lyrics that look like references to Hughes’s The Iron Man. Here’s more: The cryptic setup for “Iron Man” — “Is he alive or dead/Has he thoughts within his head” — don’t refer to the comic book; but they might certainly be inspired by Hughes’s tale of a metal creature whose origins and purpose are never explained. (“Where had he come from? Nobody knows. How was he made? Nobody knows.”)

Also, when Ozzie sings, “Now the time is here/For Iron Man to spread fear/Vengeance from the grave/Kills the people he once saved,” this is precisely what readers expect will happen once the Iron Giant digs his way out of the grave. (SPOILER: It doesn’t.) Of course, Stark also comes back from the brink of death: “The machine is keeping me alive! ALIVE!”

INTERLUDE

Sabbath’s Geezer Butler has claimed that “Iron Man” is a dystopian “science fiction story” that he dreamed up after seeing “a lot of things in the news about pollution and nuclear war.” In Martin Popoff’s 2006 Black Sabbath biography, Doom Let Loose, Geezer says:

The title was from a comic book, Iron Man; [but] it was an ecological theme. We were all very environmental at the time, and it was about this entity that turns into metal and is incapacitated at the end, just lying there. He can’t talk at the end of it, but he has this knowledge that can save the earth from catastrophe…. I was into English comics but not really American comics. I think Ozzy just came up with the title “Iron Man.” When we were writing that song, Ozzy just threw in a line about Iron Man… I didn’t really know about the comic at the time, though.”

This interview would seem to indicate that “Iron Man” was influenced neither by the comic book (except for the title) nor by Hughes’s story!

But I don’t buy it. Geezer is either fibbing (to avoid being sued for copyright infringement; to avoid being called a plagiarist) or he’s confused. The song’s themes — the entire Earth imperiled by war, or some other man-made planetary apocalypse (e.g., technological, environmental); a man who has seen this apocalyptic future but cannot communicate his vision to others; a man filled with a desire for revenge (but on who?); a man paralyzed, as though trapped in an invisible iron prison — were cobbled together primarily from Iron Man’s origin story and Ted Hughes’s heady children’s book. The question is: Why?

HILOBROW

Because Sabbath’s “Iron Man” is an antiwar song, that’s why.

During the Vietnam War era, and again today, those of us who aren’t off fighting in a senseless war — and who recognize that it’s a senseless war — gain cold comfort from the shrill middlebrow arguments we find in liberal magazines and on op-ed pages. But Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man” is cathartic. It forces listeners to experience man’s inhumanity to man, to experience for a moment what it’s like to be crippled and deformed by, say, explosive ordnance. Or by the everyday indignities, injustices, and absurdities of contemporary life.

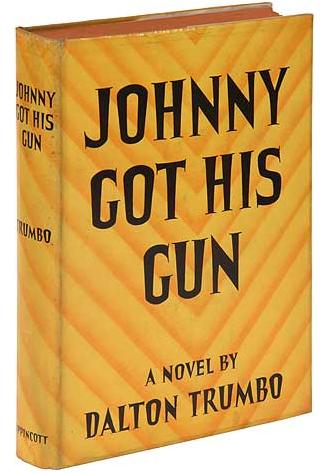

This is what heavy metal is all about. Metallica’s popular antiwar song, “One,” was inspired by Dalton Trumbo’s 1939 novel, Johnny Got His Gun, whose narrator is a soldier whose limbs and face have been blown off. Like Stan Lee’s Tony Stark, Trumbo’s Johnny is a living casualty of military violence. Like Hughes’s Iron Giant, Johnny is a terrifying sight; war and violence have transformed him into an alien and a freak, one who’s paralyzed, helpless — he’s unable to communicate the terrible lesson he’s learned, about the futility of war, its unheroic anti-glory.

Why didn’t they want him? Why were they shutting the lid of the coffin against him? Why didn’t they want him to speak? Why didn’t they want him to be seen? Why didn’t they want him to be free? … If the war was over then all the dead had been buried and all the prisoners had been released. Why shouldn’t he be released too? Why not unless they figured him as one of the dead and if that was true why didn’t they kill him why didn’t they put a stop to his suffering? Why should he be a prisoner? He had committed no crime. What right had they to keep him? What possible reason could they have to be so inhuman to him?

Why? why? why?

And then suddenly he saw. He had a vision of himself as a new kind of Christ as a man who carries within himself all the seeds of a new order of things. He was the new messiah of the battlefields saying to people as I am so shall you be. For he had seen the future he had tasted it and now he was living it. He had seen the airplanes flying in the sky he had seen the skies of the future filled with them black with them and now he saw the horror beneath….

That was it he had it he understood it now he had told them his secret and in denying him they had told him theirs.

He was the future he was a perfect picture of the future and they were afraid to let anyone see what the future was like. Already they were looking ahead they were figuring the future and somewhere in the future they saw war. To fight that war they would need men and if men saw the future they wouldn’t fight. So they were masking the future they were keeping the future a soft quiet deadly secret.

Trumbo’s Johnny has “traveled time/For the future of mankind.” Not literally, but metaphorically: He has seen the future; what’s worse, having been mangled and crippled by war, he’s become the future. Now, “Nobody wants him/He just stares at the world/Planning his vengeance/That he will soon unfold.”

What is his vengeance? The same vengeance that Ted Hughes’s Iron Man wreaks: not destruction, but peace.

They knew that if all the little people all the little guys saw the future they would begin to ask questions. They would ask questions and they would find answers and they would say to the guys who wanted them to fight they would say you lying thieving sons-of-bitches we won’t fight we won’t be dead we will live we are the world we are the future and we will not let you butcher us no matter what you say no matter what speeches you make no matter what slogans you write….

If you make a war if there are guns to be aimed if there are bullets to be fired if there are men to be killed they will not be us. They will not be us the guys who grow wheat and turn it into food the guys who make clothes and paper and houses and tiles the guys who build dams and power plants and string the long moaning high tension wires the guys who crack crude oil down into a dozen different parts who make light globes and sewing machines and shovels and automobiles and airplanes and tanks and guns oh no it will not be us who die. It will be you.

This is the very essence of heavy metal. And here we discover what highbrow and lowbrow have in common: Rage, helplessness, despair, iron(y). Middlebrow is about the tidy dialectical synthesis, having your cake and eating it too, the win-win situation. Middlebrow is about optimism, progress, solutions.

Anyone who desires nothing so much as to prevent humankind from tearing itself to pieces, but who feels paralyzed, helpless, tongue-tied — and therefore full of inarticulate rage, perhaps even a desire for revenge, not on humankind generally but on Trumbo’s masters of war — is an Iron Man.

We’re all Iron Man.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).