10 Best Adventures of 1904

By:

February 15, 2019

One hundred and fifteen years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my 100 Best Adventures of the Oughts (1904–1913)*

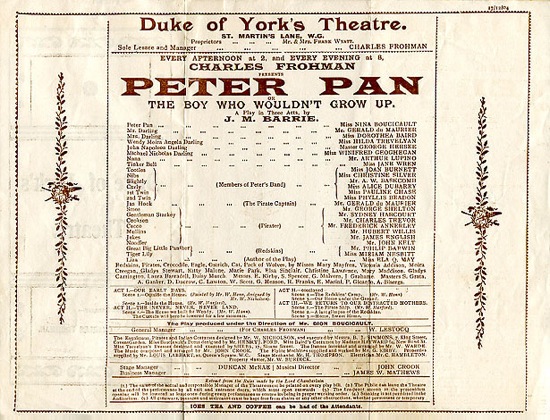

- J.M. Barrie’s fantasy adventure Peter Pan. Peter Pan began as a play, which debuted in London in 1904; the author then developed it into a novel, which was published in 1911. In both versions, the titular character — Peter Pan, the fearless, innocent, conceited, heartless boy who wouldn’t grow up — eavesdrops on the bedtime stories told by Mrs. Darling to her children Wendy, John and Michael. Discovered by Wendy, Peter invites her to fly with him to Neverland to be a mother to his gang, the Lost Boys. Wendy and her brothers fly to Neverland — narrowly avoiding disaster — then accompany Peter and the Lost Boys on various escapades… such as rescuing the princess Tiger Lily from the evil Captain Hook and his pirates. Wendy begins to miss her parents, but before she can take her brothers and the Lost Boys back to England, she is kidnapped by Hook. Peter’s fairy, Tinker Bell, meanwhile, sacrifices herself by drinking poison intended for Peter. (In the play’s most famous moment, Peter turns to the audience and begs those who believe in fairies to clap their hands.) Will Peter rescue Wendy and the others? And if he succeeds, will they stay with him in Neverland? Fun facts: Walt Disney obtained the animation rights to Peter Pan in 1935, but the movie wasn’t completed until 1953. There have been several musical productions of the play starring Mary Martin, Sandy Duncan, and Cathy Rigby as Peter Pan. As for the various live-action movie adaptations, the only one I like is Paramount’s 1924 silent movie starring Betty Bronson.

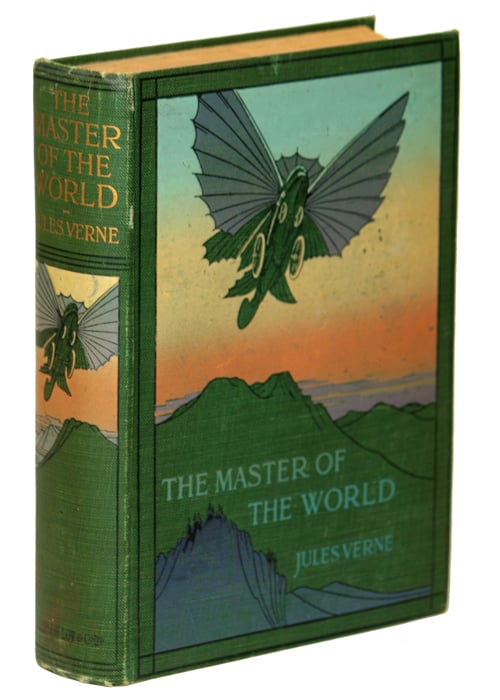

- Jules Verne’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Master of the World. In this sequel to Verne’s 1886 adventure Robur the Conqueror, FBI(-ish) Chief Inspector Strock arrives in North Carolina to investigate what appears to be an imminent volcanic eruption. Meanwhile, a supercar is spotting traveling at 120 miles per hour; and a speedboat/submarine is glimpsed in the waters off New England. Aha! The brilliant inventor Robur is back, and this time he has invented a ten-meter long multi-purpose vehicle, The Terror. Determined to have it for military purposes, the feds first attempt to buy the machine, then attack Robur. With a captive Strock aboard, Robur escapes in The Terror over Niagara Falls, then challenges God by heading into a Caribbean thunderstorm… at which point his amazing craft is shattered by lightning. Fun fact: Is this one of Verne’s best novels? No! But it demonstrates the context from which Radium Age science fiction emerged. Here we see one of the genre’s pioneers, at the end of his career (and life), questioning man’s ability to use science and technology to benefit humankind.

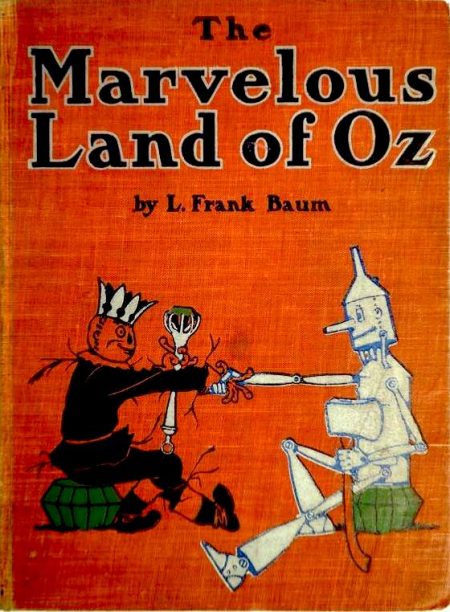

- L. Frank Baum’s Oz fantasy adventure The Marvelous Land of Oz (ill. John R. Neill). In the first sequel to the bestselling The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), an orphan named Tip cobbles together a wooden scarecrow of sorts, with a pumpkin head — in order to startle his guardian Mombi, a cruel witch. Mombi uses a life-giving powder to animate “Jack Pumpkinhead,” thus introducing one of L. Frank Baum’s great characters. Tip steals the powder, animates a wooden sawhorse for Jack to ride, and flees for his life before he’s transformed into a garden ornament. Baum wrote The Marvelous Land of Oz with a stage production in mind, hence Tip’s encounter with General Jinjur and her chorus line-like female army… who are headed to the Emerald City to depose the Scarecrow. During the ensuing chaos, Tip and Jack help the Scarecrow flee; they head to the castle of the Tin Woodman, who now rules the Winkie Kingdom. Jinjur recruits Mombi to help stop the counter-revolution, so Tip and his friends must recruit more unlikely comrades — including Mr. Highly Magnified Woggle-Bug, Thoroughly Educated, and a field-mouse army. In the end, the good witch Glinda informs the counter-insurgents that the rightful ruler of Oz is Ozma… a princess who’d been turned into a boy! But what’s become of her? Fun facts: Elements from The Marvelous Land of Oz were incorporated into the 1985 movie Return to Oz — whose stop-motion animation (by Will Vinton) and animatronics are, at times, truly terrifying.

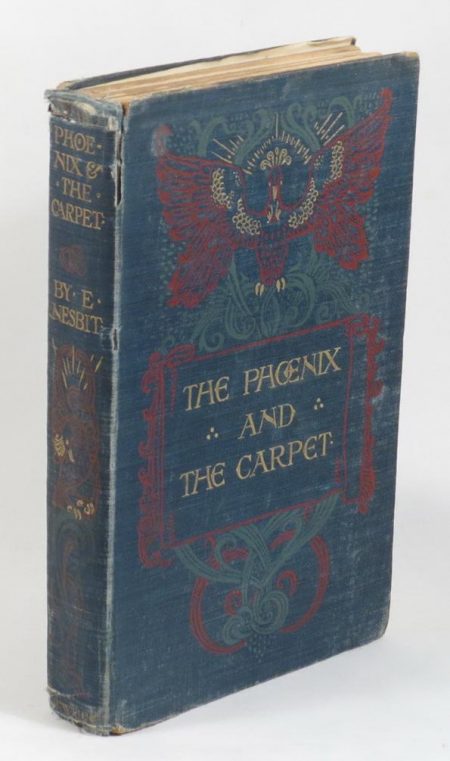

- E. Nesbit’s children’s fantasy adventure The Phoenix and the Carpet. Nesbit’s writing is extraordinary, because: she is drily witty, in a way that makes her writing as entertaining to adults as to children; she was politically progressive, so there’s not quite as much to cringe at as we find in her contemporaries’ writing; and her conception of how magic and the everyday world might interact — the brilliant idea that magic has strict rules which need to be puzzled out, painfully — would prove influential on everyone from P.L. Travers to Edward Eager, C.S. Lewis, Diana Wynne Jones, and J.K. Rowling. Here, siblings Cyril, Anthea, Robert, and Jane, whom we first met in Five Children and It (1902), discover a flying carpet and an ancient Phoenix — a magnificent, vain creature which expects to be worshipped by modern Londoners. Over the course of several adventures, the children wear out the carpet’s fabric — which causes it to malfunction, entertainingly. There’s a burglar, a buried treasure, and a church jumble sale that goes entertainingly awry. Will the children figure out the best possible use for the carpet before it’s too late? Fun facts: The final installment in the Psammead series is The Story of the Amulet (1906). I’m also a fan of Nesbit’s Bastable series, her House of Arden series (including 1908’s The House of Arden), and her other children’s novels — including The Railway Children (1906) and The Enchanted Castle (1907).

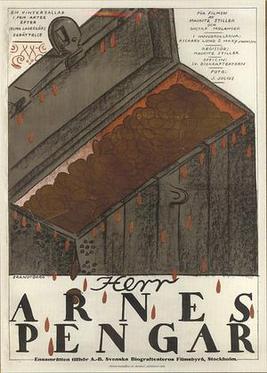

- Selma Lagerlöf’s occult thriller Herr Arnes penningar (English title, The Treasure). In this Nordic-noir novella, when three brutal robbers invade and rob a wealthy household in Solberga, a town near Stockholm, Sweden, only one member of the family, the adopted orphan Elsalill, survives the massacre. She desires revenge — but as far as anyone knows, the robbers were killed when their sled broke through the surface of the frozen waterways leading to the ocean. Elsalill falls in love with Sir Archie, a wealthy soldier of fortune who arrives in town with two companions shortly after the robbers vanish; however, the ghost of her foster sister intercedes in their romance. Furthermore, Elsalill’s ghostly companion begins to provide clues regarding the true identities and whereabouts of the murderous robbers. It’s like a detective novel crossed with a Scandinavian saga — plus a ghost story. It’s very atmospheric and gloomy, with bloody footprints, raging blizzards, ships unable to break through uncannily thick ice, and mounting tension — which ends in a final act of violent self-sacrifice. Plus, there’s a dog, Grim, who knew what was going on the entire time. Fun facts: Adapted in 1919 by Mauritz Stiller as a movie, Herr Arnes pengar, starring Richard Lund, Hjalmar Selander, Concordia Selander, and Mary Johnson. In 1909, Lagerlöf would become the first female writer to win a Nobel Prize.

- Winston Churchill’s frontier adventure The Crossing. When he hears that his father, a frontiersman, has been killed, twelve-year-old David Richie runs away from a comfortable life in Charleston — and heads for the wilds of Kentucky. The book’s title refers to the great movement of European settlers from east to west, across the American continent; our young protagonist’s journey, which takes place during the Revolutionary War, is emblematic of that epic migration. David makes it through the Cumberland gap — the key passageway, for pioneers, through the lower central Appalachians — only to discover that the British are encouraging Indian raids against Kentucky settlers. So he enlists as a drummer boy under George Rogers Clark — a real-life character, leader of the Kentucky militia — in a campaign to weaken British influence in the Northwest Territory. In the second part of the book, a grown-up David, who is now studying law, is reunited with his foster family… and must rescue his childhood companion, Nick, from a madcap scheme by some Kentuckians to capture New Orleans, from Spain, for the newly formed United States. Daniel Boone, John Sevier, Andrew Jackson, and other now-iconic Americans all show up. Fun facts: Winston Churchill was an American novelist, from Missouri; he was not related to the British statesman. The Crossing is considered his best novel. Churchill’s earier novel, Richard Carvel (1899), was a massive best-seller.

- George Barr McCutcheon’s Ruritanian adventure Beverly of Graustark. In this sequel to Graustark: The Story of a Love Behind a Throne (1901), which was set in the fictitious Eastern European principality of Graustark, Prince Gabriel — villain of the earlier novel — escapes from prison and recaptures the throne of Dawsbergen, Graustark’s southern neighbor. Gabriel’s brother, the handsome and good Prince Dantan, disguises himself and goes into hiding; meanwhile, Dawsbergen and Axphain (Graustark’s northern neighbor) scheme to invade Graustark. All of this is the background to a romance story about Beverly, an American southern belle who follows her friend, Graustark’s princess, home for the summer. En route to the capital city, Edelweiss, Beverly is lost in the mountains and rescued by Baldos, a dashing and gallant bandit chief; the section of the novel in which the witty, confident Beverly wanders in the wilderness with the bandits is particularly fun. As with McCutcheon’s first Graustark yarn, there are thrills and chills aplenty, political intrigue, and a surprise twist at the end. Fun facts: Adapted as a 1926 silent romantic comedy starring Marion Davies. Subsequent Graustark series installments include Truxton King (1909) and The Prince of Graustark (1914). McCutcheon is today best remembered for his 1902 novel Brewster’s Millions, which was memorably adapted as a Richard Pryor/John Candy joint in 1985.

- Joseph Conrad’s treasure-hunt adventure Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard. Charles Gould owns an important silver-mining concession near the port of Sulaco, in the western province of Costaguana, a fictional South American country that Conrad seems to have modeled on Colombia. Fed up with Costaguana’s never-ending cycle of tyranny and revolution, Gould uses his wealth to support the military dictator Ribiera. When this leads to even more chaos, Gould orders his influential and incorruptible head longshoreman, the Italian expat Nostromo, to smuggle a shipload of silver out of the country — in order to keep it out of the hands of the revolutionaries’ General Montero. The silver ends up buried on a deserted island, guarded by a young journalist, Martin Decoud; Gould and everyone else, however, believe that the treasure has been lost. Nostromo heads back to Sulaco, where he daringly helps save the town’s powerful leaders from the revolutionaries. Afterwards, consumed by resentment — because he is not admitted into Sulaco’s elite circles, despite his exploits, Nostromo decides to recover the hidden silver… but what has become of Decoud? Will Nostromo ever attain his heart’s true desire? Or will forces beyond his control forever frustrate him? Fun facts: Serialized in 1904, in the London magazine T.P.’s Weekly, Nostromo is now considered one of the best English-language novels of the 20th century. F. Scott Fitzgerald once said, “I’d rather have written Nostromo than any other novel.”

- G.K. Chesterton’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Napoleon of Notting Hill. Before Francis Fukuyama’s 1989 essay “The End of History?” posited that the universalization of Western liberal democracy may signal the endpoint of humanity’s sociocultural evolution, G.K. Chesterton’s first novel described a stultifying, Wells-esque utopian world order — in the year 1984 — where religion has been banished, and violence is unknown, but at the cost of particularism, creativity, and progress. So bored are the British that they randomly select Auberon Quin — an eccentric prankster — as their king. Among other proto-Pythonesque provocations, Quin declares that each of London’s neighborhoods will henceforth be an independent city-state, and requires their lord mayors to dress in medieval costumes. Most Londoners enjoy this game… but ten years later, when the other cities plan to build a road that passes through Notting Hill, 19-year-old patriot Adam Wayne foments a protest movement. Wayne, the titular Napoleon of Notting Hill, turns out to be a born military tactician, and soon enough an all-out conflict, featuring swords and halberds, has broken out between London’s neighborhoods — prefiguring the 1981 Judge Dredd story “Block War.” Chesterton doesn’t gloss over the tragedy and stupidity of war… but ultimately, his point is that a healthy, vibrant society demands a little tragedy. Fun facts: The Irish revolutionary leader Michael Collins, who was 14 when the book was published, is known to have greatly admired The Napoleon of Notting Hill, which helped inspire his Irish nationalism. Also, it has been speculated that Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, which is also set in a dystopian British utopia, takes place in that year as an homage to Chesterton’s novel.

- Jack London’s philosophical sea-going adventure The Sea-Wolf. In this grown-up version of Kipling’s Captains Courageous, an effete young intellectual — Humphrey van Weyden, whose favorite philosophers are Nietzsche and Schopenhauer — is rescued from a shipwreck in the San Francisco Bay by a brutal schooner captain, Wolf Larsen, who takes his unwilling passenger along on a seal-hunting voyage. Larsen is a quasi-Nietzschean cynic who believes in nothing but the pursuit of pleasure and the triumph of strength over weakness; he thoroughly enjoys browbeating “Hump” while forcing him to do menial work and learn how to defend himself. There are a few thrills: a mutiny attempt, during which Larsen singlehandedly fights half a dozen mutineers; a survival ordeal on an uninhabited island; a violent storm. And there is an unsatisfactory, distracting romance plot — which begins when Larsen also rescues a beautiful woman. But primarily, this is a novel of ideas in which London stress-tests such un-Nietzschean notions as the eternal soul and inherent good. Fun facts: Ambrose Bierce wrote, “The great thing [about The Sea-Wolf] is that tremendous creation, Wolf Larsen… the hewing out and setting up of such a figure is enough for a man to do in one lifetime.” Rugged actors who have portrayed Larsen in film adaptations include: Noah Beery (1920), Edward G. Robinson (1941), Barry Sullivan (1958), Chuck Connors (1975), Charles Bronson (1993), Stacy Keach (1997), and Sebastian Koch (2009).

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.