Published just before the Great Recession of 2008, the Idler’s Glossary took an irreverent approach to the centrality of work in our daily lives. Mark Kingwell’s Introduction argued that the values of work are too dominant in too much of life… and noted that they’ve created a host of phrases and terms which help sustain the fiction that work as we know it is a natural, inevitable, and permanent state of affairs. Joshua Glenn’s glossary commented on two hundred-plus such phrases and terms, from Amusement, Beautiful Loser, and Couch Potato to Truant, Vacation, and Whiling Away the Hours.

“An odd and beautiful book, The Idler’s Glossary imagines an alternate world where free time is valued as much as cubicle time. We need to be idle more often, need to have time to read and ponder, so that we can dream up better worlds instead of just living in this crappy one.” — io9, Gawker Media’s science fiction blog.

“Though constructed as a glossary it’s essentially a manifesto, shot through with author Joshua Glenn’s philosophical outlook on life and quotes from Eastern and Western sages from Krishna to Foucault.” — Utne Reader’s Great Writing blog

“A worthy tome, illustrated by the stupendously talented Seth” — Boing Boing

“Fulminates most entertainingly against labour and industrial amusement, pays happy respect to its guiding spirits Lin Yutang and Henry Miller, gambols gaily in etymological thickets, and poses crucial questions for further research.” — The Guardian

“A vocabulary-expanding manual for the bootless, malingering and lotus-eating types among us.” — The New York Times’ ArtsBeat blog

“This little book explains — nay, argues — for the moral superiority (over work, slacking and even leisure time) of idleness.” — The Washington Post Book World’s Short Stack blog

“A playful little volume that traces the history and etymology of hundreds of idler-specific terms and phrases, and attempts to set the record straight on the benefits of idle hands.” — New Hampshire Public Radio’s show “Word of Mouth”

“With a trim size perfect for fitting into your pocket to read during a long day of non-work at the park, The Idler’s Glossary is your terminological introduction to how best to kill time.” — Dwell

“A utopian book, one that goes beyond the duality of work versus nonwork, beyond leisure activity and slacker cynicism to try to reach a Zen-like ideal of idleness. While the book is tongue in cheek, its irreverent approach to the centrality of work in our daily lives may resonate more deeply in light of recent economic events.” — Los Angeles Times Book Review’s Jacket Copy blog

“Rich fare for lean times.” — Katherine A. Powers, Boston Globe

“A great pleasure and a great read.” — Tom Hodgkinson, editor of The Idler

“Who better to offer sage advice about post-hypercapitalist living than two lifelong experts on idling, goldbricking, scrounging, dawdling, quitting, napping, mooching, laying about, and dreaming?” — Fantagraphics Books’ blog, FLOG!

“The current economic climate might induce worried people to work harder and longer than ever before, but as this delightful and compact volume shows in alphabetical order, perhaps we’ve got it all wrong.” — Sarah Weinman

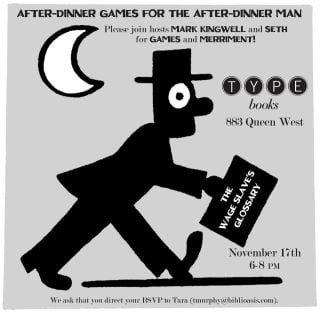

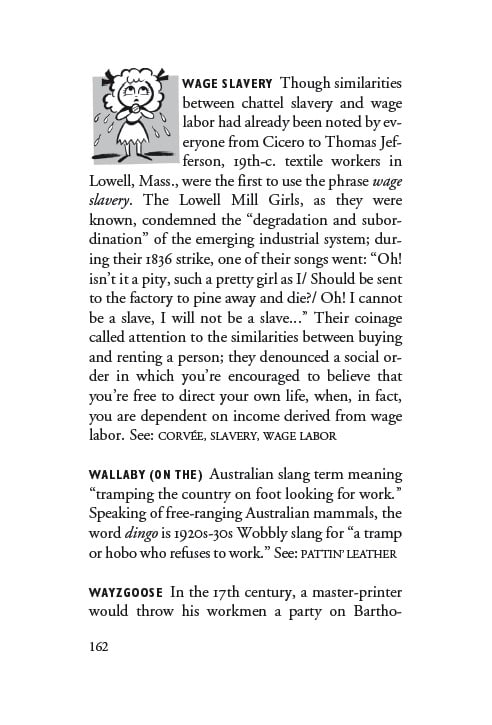

The Wage Slave’s Glossary (Biblioasis) criticizes and analyzes what the Lowell Mill Girls were the first to name wage slavery. Joshua Glenn’s glossary of over 200 terms interrogates not only office jargon (from Bandwidth to Telecommuting) but labor-related slang and workplace terminology (from After-Dinner Man to Workbrickle) used to naturalize wage slavery from the dawn of industrial capitalism to the present day. Mark Kingwell’s philosophical Introduction criticizes the “work idea” itself, and its corollaries — including bureaucracy and bullshit.

The WSG, a sequel to Glenn and Kingwell’s equally subversive Idler’s Glossary, which was presciently published just before the Great Recession of 2008, is designed and wittily illustrated (as was the IG) by the great cartoonist Seth.

Purchase both books for the aspiring idlers and disgruntled wage slaves in your life!

The World Socialist website reports that

Of [IBM’s] more than 20,000 employees in Germany, at least 8,000 will lose their permanent jobs and be replaced by flexible external workers. The programme, called “liquid,” provides for outside workers to be hired flexibly as required. The hiring of external IT experts and other specialists is to take place via a specially created Internet platform, in the form of a so-called Cloud.

The career counseling blog Career Calling had a few nice words to say about the WSG. Including these: “I strongly recommend this book, which is wise, witty, and — too often — sad.”

The pro-Palestine blog Intifada: Palestine ran an interview with Mark Kingwell, by Kourosh Ziabari. Excerpt:

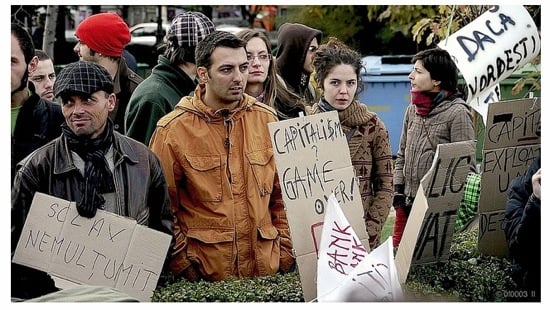

KZ: What’s your analysis of the Occupy Wall Street movement? Do you think that it was inspired by the Arab Spring? Why the American protesters call themselves the 99% of the population and question the authority and supremacy of the 1%? Is there anything wrong with capitalism and corporatism that has exhausted the people? What’s your view about the police crackdown on the protesters?

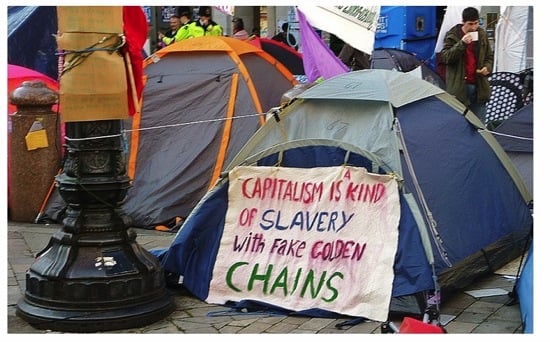

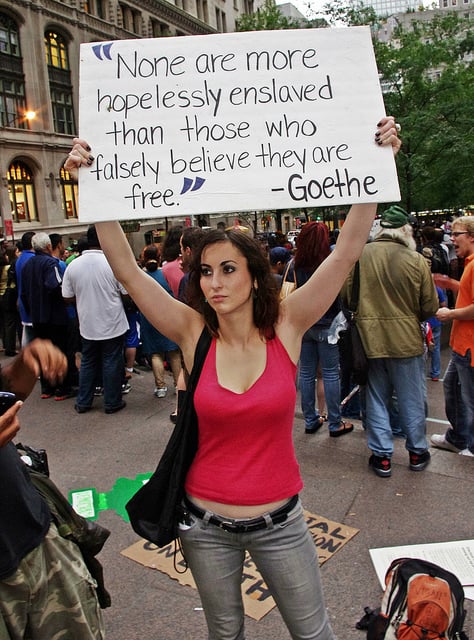

MK: I’m certain there was some inspiration taken from the Arab Spring, yes. The very topic of OWS’s connection to the Arab Spring became a contentious issue here, however. Critics of OWS — who grew more repressive and condescending by the day, until the parks were forcibly cleared — were vehement that no comparison with Arab Spring was valid, or even allowed. It was if popular uprising were democratic, and wonderful, but only if they happened somewhere else. One particularly loathsome journalist labeled the OWS protesters as ‘capitalism’s spoiled children’, as if they had no right to object to a system than does not work, that is grossly unjust, and that is sustained by only a sham politics of puppet candidates permanently indebted to the monied interest. Shut up, and get back to shopping for gadgets! It was a disgusting spectacle of provincial, toy-time fascism.

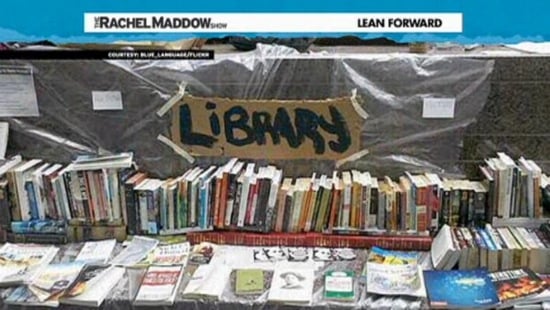

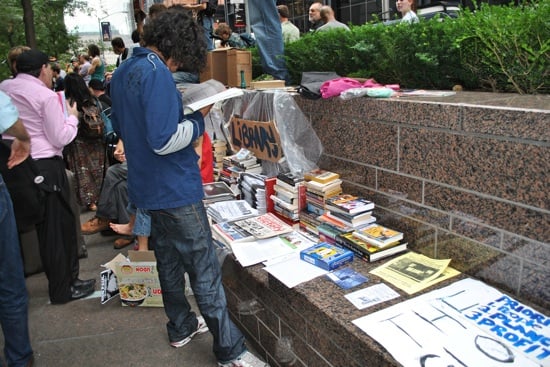

I was especially upset about the police crackdown because of the cavalier way in which ‘health and safety concerns’ became a blanket justification for police action. The books in the OWS library — including a small volume I co-write, The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011, with Joshua Glenn) — were tossed in garbage containers. In a strange way, this blithe trashing of books was worse than setting fire to them. For this neo-liberal police state, books are not even dangerous or important enough to burn. A depressing thought.

It remains to be seen what political upshot there is from OWS. My own feeling is that the objections to corporate capitalism will not be as easy to eradicate as were a few tents and bodies. They used to say to us left-wingers, when we were young, that socialism is a nice idea, only it doesn’t work. Here’s an update: capitalism doesn’t work either, and it’s not even a nice idea.

We stopped adding regular WSG News updates on Xmas, 2011. From now on, we’ll be dilatory about it.

Brandeis English prof John Plotz published a fine essay in the NYTBR today about acedia, the “noonday demon.” Acedia is one of the topics tackled in The Idler’s Glossary. Here’s an excerpt from Plotz’s essay:

These days, when we try to get a fix on our wasted time, we use labels that run from the psychological (distraction, “mind-wandering” or “top-down processing deficit”) to the medical (A.D.H.D., hypoglycemia) to the ethical (laziness, poor work habits). But perhaps “acedia” is the label we need. After all, it afflicted those whose pursuits prefigured the routines of many workers in the postindustrial economy. Acedia’s sufferers were engaged in solitary, sedentary, cerebral effort toward a clear final goal — but a goal that could be reached only by crossing an open, empty field with few signposts. The empty field is the monk’s day of spiritual contemplation in a cell besieged by the demon acedia — or your afternoon in a coffee shop with tiptop Wi-Fi.

On Dec. 23, HiLobrow published a conversation between Kingwell and Glenn about wage slavery and The Wage Slave’s Glossary. Excerpt:

JOSHUA GLENN: In the Labor Day-themed issue of The New York Times’ Sunday Review, former US secretary of labor Robert B. Reich urged policy makers to boost the purchasing power of the middle class by improving public schools and public transportation, expanding access to early childhood education and higher education, maintaining strong labor unions, enlarging safety nets, requiring big companies to pay severance to American workers they let go and train them for new jobs, pegging the minimum wage at half the median wage, raising taxes on the rich and lowering taxes on the poor, and in general spreading the gains of globalization and technological change more equitably.

Compared with the Tea Party-goaded Republican economic agenda, Reich’s (slightly left-of-center) neoliberal vision of the good life is progressive, even pie-in-the-sky. But our two books refute the proposition that boosting the purchasing power of the middle class will make America, as Reich argues, “a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone.” (As the child and sibling and husband of progressives, this makes me feel rather like an enemy of the people.) Instead, we seek to defend, as you write in the WSG, “an idea of life free from the depredations of getting and spending, labour and its sale” — whether in the US, Canada, or anywhere else in the world.

Though we purposely don’t offer a blueprint of a better, richer, fuller life for all, our two little books are nevertheless deeply idealistic. Although we might agree with what passes for progressive political thought today about, say, the importance of improving public schools and public transportation, enlarging safety nets, and various other particulars, we disagree with the notion — taken for granted by Republicans and Democrats, Conservatives and Liberals — that free markets, free trade, and the unrestricted flow of capital are key to producing the greatest social, political and economic good. And we disagree with the notion, taken for granted by everyone, that the more we work, the better off we’ll be. Ours is an idler idealism: we demand not strong labor unions, higher minimum wage, or lower taxes, but freedom. Or, better: FREEDOM!

Does that make us enemies of the people?

MARK KINGWELL: I think it makes us anarchists as opposed to socialists. Though I do sometimes describe my own politics as democratic-socialist, there is an increasingly stark division between those who think boosting productivity and creating more jobs are the only solutions to current ills and those, like us, who think the model is so broken that this sort of fix will just extend the troubles. We’re really saying that everyone needs to rethink their own ideas about life, rather than just trying harder and harder to buy in to a system we know is unjust and, massively evident since 2008, dysfunctional. I think I say somewhere in the introduction to the Wage Slave’s Glossary — don’t change the system, change yourself! Or as you put it: FREEDOM!

The key to this, as we suggest, is language. What anthropologists call the language upgrade allowed evolving humans to make a huge leap in their ability to coordinate actions and achieve things. Language is the key to civilization as we know it. But language is supple. It can be turned and twisted to bad purposes, it can be used to manipulate, coerce and deceive. The premise of both our books, but especially The Wage Slave’s Glossary, is that ideas creep into consciousness, take up residence there, and influence behavior in large measure through vocabulary. How we think about work and how we talk about it are inextricable. What I call the work-idea — the presupposition that everyone must work, and that work will set you free — is one of the largest and most successful ideological deceptions in human history. To the extent that ‘everyone thinks this’, it seems beyond challenge. But we’re trying to subvert that ideology, and doing so obliquely with a book-form that is not usually considered critical or political at all, the ‘mere’ glossary.

This idea that work is not the key to human happiness is a more radical message than anything to be heard in the mainstream political discourse, yes, and that will make it seem kooky to some. And we never want to stop being playful about the ways we deliver the message. But the serious part is the age-old philosophical demand, the duty to examine your one and only life. And then — well, I suppose our book is not quite as beautiful as the Archaic Torso of Apollo (though with Seth’s wonderful art it’s pretty darn beautiful) but its ultimate demand is the same as the one Rilke saw in all great art: You must change your life!

Yunchtime really gets it!

Perhaps Bob Dobbs was right… the best choice is slack. It is then heartwarming to see the success of the Idler’s Glossary and the follow-up volume, the Wage Slave’s Glossary, in which the essence of slack is conveyed in the seemingly innocent format of a list of words and definitions. It’s worth listening to the interview with co-author Mark Kingwell, for some of his take on the terms, such as “wage slave” which was:

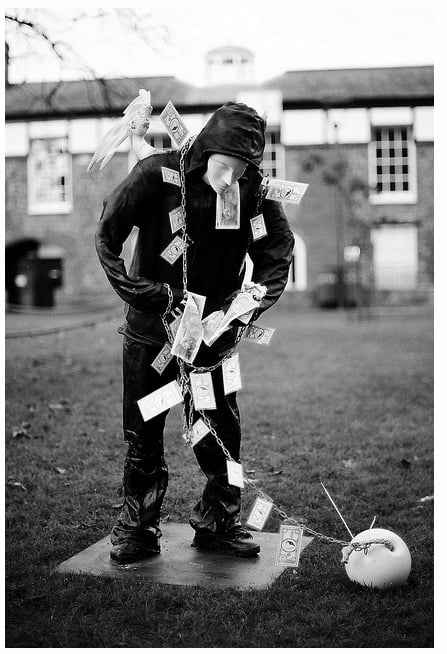

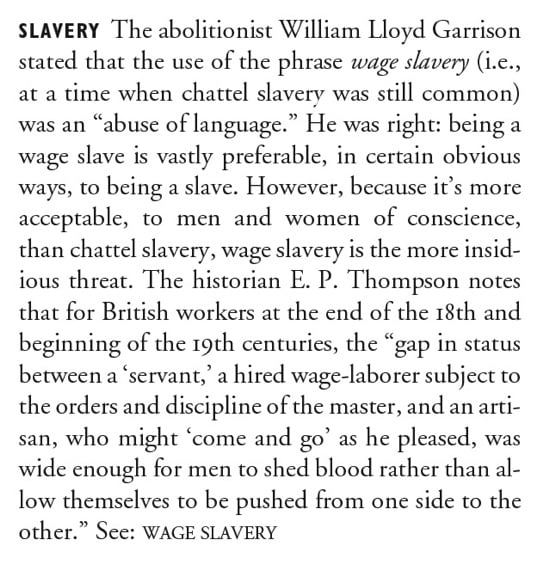

“popularized by the Lowell mill girls, though the term is bit older. The idea is that you have a job, but you are enslaved to the conditions of your own labor because you have to have that wage to live. It’s rooted in Marxist analysis of labour and consumption. And the idea is that you can’t get out from under, because in a classic situation, you have to buy your supplies at the company store, so the wages the company pays you are channeled right back into the company. You may not be a chattel slave, in the ancient sense, in that you are physically owned by the company or by a person, but you’re enslaved by these conditions. At the time there was a lively debate between socialists and anarchists, socialists wanted to improve working conditions through unionization and collective bargaining, and arnarchists wanted to say, look, it’s this whole idea of work that needs to be put into question. And the more you cooperate with management, the more you perpetuate the system.”

This is straight out of Kropotkin, if I’m not mistaken. Then Kingwell compares idler with slacker:

“There is a distinction between the idler and the slacker. the slacker is someone who is self-consciously avoiding work, as a result the slacker is still bound by dictates of work as something that he or she is avoiding. The idler, by contrast, is taking time and striking out in a whole new direction of personal preference and self development.”

The beauty of the “idler,” in Kingwell’s definition, is the rejection of the entire working paradigm. There is a not so subtle sub-text which is the obvious suggestion that anarchism is really the solution.

On the other, hand, I would take issue with the usage of “idler” and “slacker” here, because I believe that there ought to be some leeway in the term “slacker” which can include the anarchistic bent of Bob Dobb’s “slack” and which is both creative and completely free of any dictates of work. But that is quibbling.

Even more amusing is to listen to co-author Joshua Glenn’s interview with Michael Dresser, in which the host shows himself to be so utterly ossified and extinct (he wants to vote for a John Wayne – Fonzie ticket in the Presidential election) that Glenn’s entire radical objective sails cleanly over his head.

So, drop away the seven veils, cast off your chains, and RISE UP as a free human being. Then DIY, amigos!

I would only point out that The Idler’s Glossary does sympathetically reference the Church of the Subgenius, in its gloss on SLACKNESS.

DAMN IT. We had an opportunity to do a joint event with anthropologist David Graeber at a New York bookstore, but the opportunity slipped away…

Here’s a nice write-up in the NYTBR about Graeber’s new book, Debt: The first 5,000 Years. Excerpt of interest to wage slaves:

“Those who have argued that we are the natural owners of our rights and liberties,” Graeber writes, “have been mainly interested in asserting that we should be free to give them away, or even to sell them.” Although “mainly” is a bit tendentious, Graeber’s point is that we ended up enslaving ourselves by thinking of ourselves as fully autonomous. As anyone who works a 9-to-5 job knows, the “right” to sell one’s labor hardly feels like privilege. …

“Debt” ends with a paean to the “non-industrious poor.” “Insofar as the time they are taking off from work is being spent . . . enjoying and caring for those they love,” Graeber writes, they are the “pioneers of a new economic order that would not share our current one’s penchant for self-destruction.”

It’s an old dream among anthropologists — one that goes back to Rousseau. In 1968, Graeber’s own teacher, Marshall Sahlins, wrote an essay, “The Original Affluent Society,” which maintained that the hunters and gatherers of the Paleolithic period rejected the “Neolithic Great Leap Forward” because they correctly saw that the advancements it promised in tool-making and agriculture would reduce their leisure time. Graeber approves. He thinks it’s a mistake when unions ask for higher wages when they should go back to picketing for fewer working hours.

Announced today: Mark Kingwell’s Introduction to the Wage Slave’s Glossary was chosen for a Best Canadian Essays of 2011 anthology, officially launched today.

On Dec. 2, The National Post (Canada) listed the WSG in its “Snap Judgments” column.

WE WANT: Mark Kingwell and Joshua Glenn’s latest point of purchase impulse-buy compendium, The Wage Slave’s Glossary (Biblioasis, $12.95). Don’t know what to “fossick” means, and why no journalist should do it? See, now you want it, too.

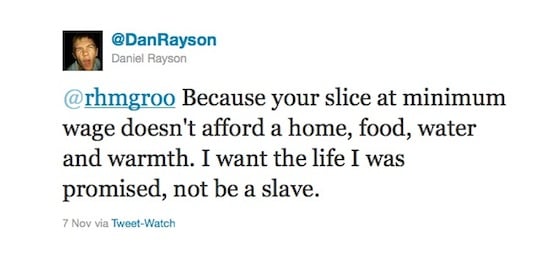

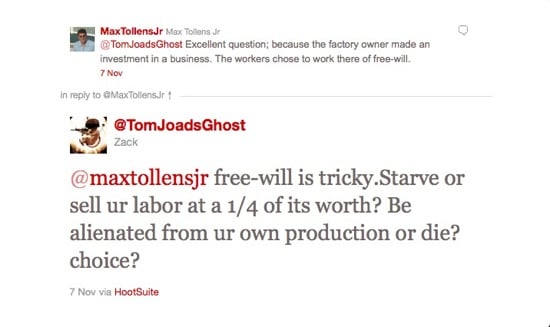

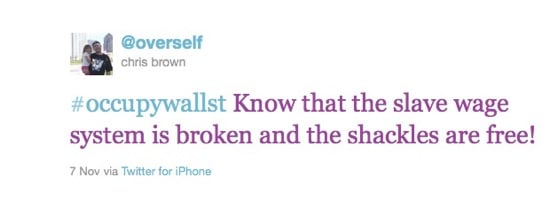

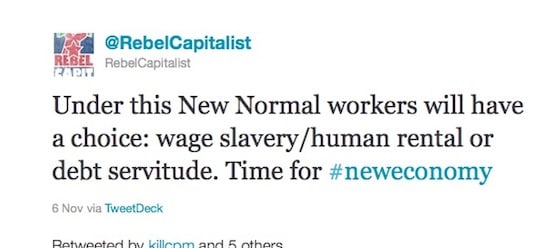

On Dec. 1, the blog Martlet posted an entry by “Dylan Action” which argued that the Occupy movement is anti-wage slavery, and as such, an idea whose time has come:

On Nov. 30, Sam de Brito, who blogs about manhood for the Sydney Morning Herald, quoted from a book titled Free to be Human by David Edwards:

The radio show Dresser After Dark interviewed Joshua Glenn about the WSG. Listen here.

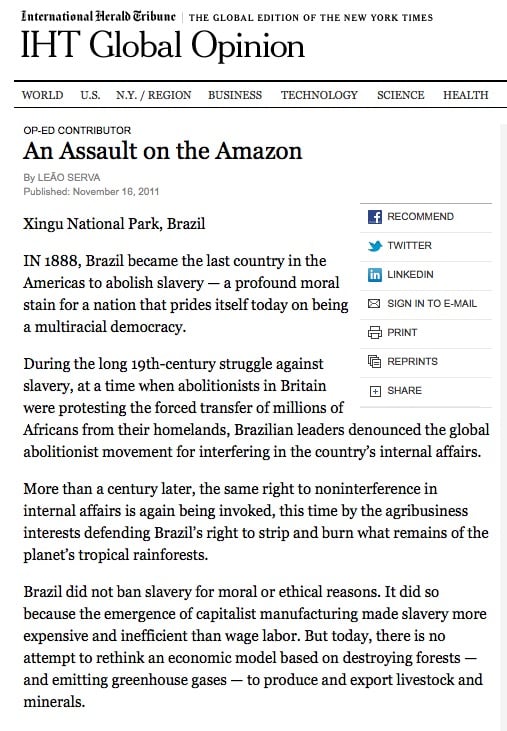

On Nov. 16, Brazilian journalist Leão Serva wrote an op-ed in the International Herald Tribune which began like so:

We noticed that an episode of The Rachel Maddow Show dedicated to the NYPD trashing of the OWS Library features a shot of the library in which the WSG is featured front and center.

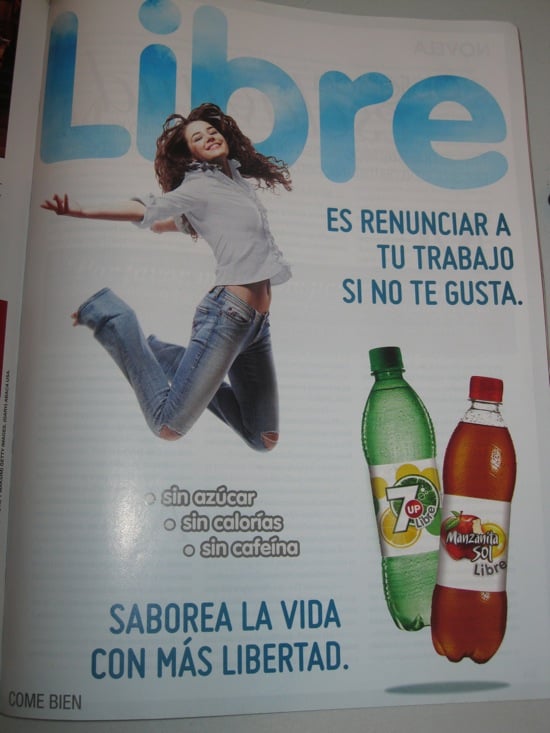

A friend in Mexico sends this 7-Up ad. “FREE… to quit your job if you don’t like it.”

Photo taken by Flickr user helenoftheways.

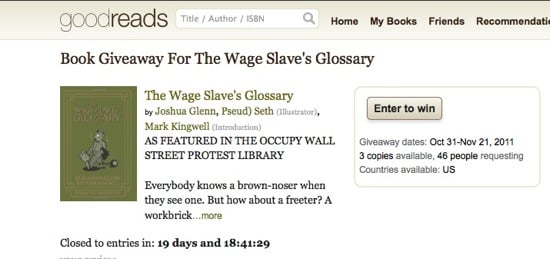

On Oct. 31, the website Goodreads announced a book giveway contest. The book? The Wage Slave’s Glossary. Enter for a chance to win — you have 20 days!

On Oct. 28, Amazon user T. Muragtroyd wrote:

This book couldn’t have come at a better time. I heard about it through the N.Y. Times and saw that the Occupy Wall Street Library had picked it up, so I went out and found a copy, and I was glad I did. There was nothing of what I was afraid of: it wasn’t kitschy or insubstantial or trying too hard to be funny. Instead I found it wonderfully incisive, satirical, contemporary, on-point. Kingwell’s introduction on Wage Slavery and Bullshit is market-savvy and goes a long way towards unpacking the rhetoric of capitalism. […] Kingwell’s essay in combination with Glenn’s incredibly wide-ranging definitions (which move from the 16th century to 2011, and include terms from Britain, China, and Japan), produces a substantial — far more substantial than you’d think for such a little book — assessment of work language. […] As Kingwell & Glenn admit, this little book may not overthrow capitalism, but it succeeds in doing what they set out to do: “highlight essential things about our predicament — philosophy’s job ever.” Five stars. And speaking of stars: the illustrations by Seth are out-of-this-world good.

On Oct. 27, Ryerson University’s School of Image Arts announced a panel discussion on the representation of labour for November 8th, at 6:30 pm, featuring WSG coauthor Mark Kingwell and German photographer Martin Weinhold. The discussion’s context is Weinhold’s Workspace Canada exhibition opening at Ryerson’s I·M·A GALLERY on November 3. Over the past decade, Weinhold has documented workers and their working conditions across Canada.

The press release notes: “The Wage Slave’s Glossary, written by Joshua Glenn and Mark Kingwell, will be on sale at the panel discussion. Glenn and Kingwell have condensed the language of labour in North American culture into a glossary that articulates the frustrations of being in the labour force today.”

The event will take place at Ryerson University, 285 Victoria Street, Fifth Floor, Room 501.

On Oct. 27, the blog Language Museum posted a nice mention of the WSG.

“In the dictionary are words borrowed from other languages that reflect office life, new words appropriate for our current economic situation and historic words whose meaning has changed (career for example).”

On Oct. 26, thought leader Mark Kingwell was interviewed about the WSG on the KKZZ (Ventura, Calif.) radio show “Brainstormin’ with Billy the Brain.” Listen to the interview here or click on the PLAY button below (skip to 4:15).

A friend points out that the WSG is well-represented in the People’s Library (the OWS Library’s catalog on LibraryThing).

Photo taken in Zucotti Park by Flickr user robthoco.

This tattoo posted to the Tumblr M’Aidez on Oct. 23.

Photo taken — at Occupy Toronto — by Flickr user Martinho.

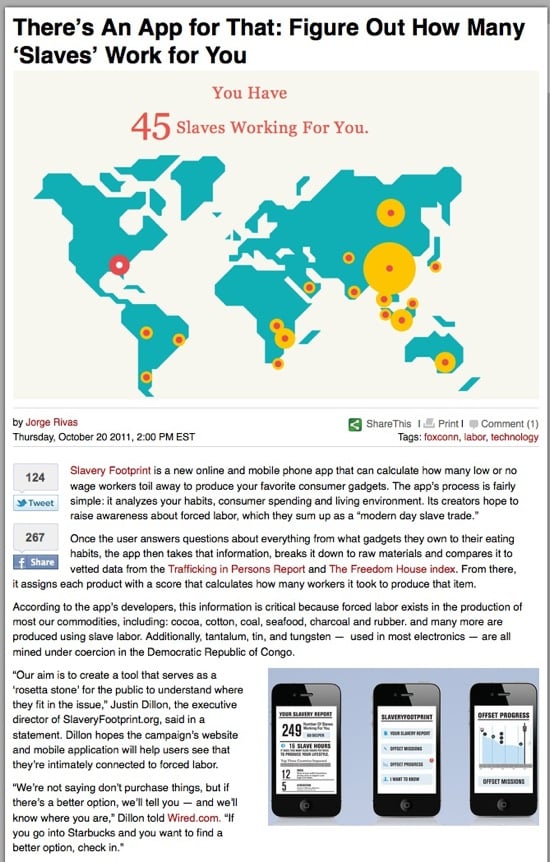

On Oct. 20, ColorLines announced Slavery Footprint, an app that calculates how many low or no wage workers toil away to produce your favorite consumer gadgets.

On Oct. 19, TIME magazine’s NewsFeed blog linked to The Atlantic’s slideshow of The Wage Slave’s Glossary. According to NewsFeed, the WSG is a collection of “modern office idioms.”

[Terms glossed by the WSG] include eyeservice, which is the practice of working only when the boss is watching. There is funemployment, a term for those who actually enjoy being out of work in this jobless era. And there is hurry sickness, a diagnosis for those who feel constantly short on time.

On Oct. 18, WSG coauthor Mark Kingwell did a Q&A with the University of Toronto’s newsfeed. Here it is:

UT: Much has been said about the Occupy movement’s lack of organization, lack of a spokesperson and or the lack of an overall coherent or single message. What do you think of the mainstream media’s reaction to the movement?

KINGWELL: There has been a consistent reaction to Occupy that leans heavily on ‘lack’ — lack of sound bite, single message, policy plan and so on. A popular protest does not need a message in the terms that suit the dominant discourse, including especially that of the media. As my friend Douglas Rushkoff put it, Occupy Wall St. (OWS) might be less like a book and more like the Internet. Times have changed; get used to it. This may go on for a while, it may mutate and shift. There are, to my mind, clear policy goals that could be articulated, but recognition of the right to protest and its simple importance as an expression of the idea that capitalism is not working is essential first.

UT: The Occupy movement does seem counter intuitive to the way things are ‘normally’ done, or is this the point?

KINGWELL: It’s a point the Situationists used to make: everyone says that protesters have to justify themselves, give reasons, articulate an overall plan and scheme of thought. But why does this not also apply to people eating in restaurants, taking planes, making stock trades? Why is dissent subject to demands for clear and comprehensive justification when the very actions that dissent wants to bring into question are not? That’s called ideological domination, and it needs to be called out, early and often.

UT: Comparing mainstream media’s reaction to the Occupy movement with that of the Arab Spring, we see a significant difference in the amount of coverage and the general attitude. How would you account for this difference?

KINGWELL: Comparisons to the Arab Spring are telling. There, it was apparently okay to have just a word — democracy — and a bunch of people mobilizing their discontent through their bodies. Here, somehow it needs further justification. Why is democracy only a good thing when it’s done somewhere else? This just makes it obvious that a lot of people, not just the so-called one-percenters, have a vested interest in keeping the current arrangement just as it is.

UT: Do you think the movement is anti-capitalist or about creating a fairer system? Is there something inherently contradictory about this movement? Many of the protestors seem to want jobs, the ability to ‘live the dream’ — yet, don’t recognize that this in itself might be the problem.

KINGWELL: I think some of the people involved want to overthrow capitalism, yes. Others just want a game that is less rigged in favour of the very few. The 99 per cent slogan is good, though of course it proves weak on analysis. (What about the person who is next in line, wealth-wise, from the last of the numerically one percent of the world’s rich? Surely he or she is still pretty damn rich…) I think of this more in terms of a clear signal: the system is broken, and it can’t be fixed by the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) or bailouts or even job-creation programs. There have to be some basic shifts — in taxation, services, the very idea of government — in order to slow and maybe someday reverse the widening income gap. Real wages of workers have consistently declined over the past three decades, even as executive compensation has risen astronomically, sometimes by 500 or 1,000 per cent or more. Not only is that obviously unjust, it is untenable. The old rap against socialism was, “Nice idea, but it doesn’t work.” You know what? Capitalism doesn’t work either, and I’m not sure it’s even a nice idea.

UT: Your latest book with Joshua Glenn, The Wage Slave’s Glossary, is listed in the collection of the OWS Library. Why do you think it has been included in the library? Does it offer protestors a glimmer of hope or confirm their worst fears?

KINGWELL: Josh and I were happy to see that the book was in OWS library and that our timing once more proved lucky, if not prescient. (The prequel to the WSG, The Idler’s Glossary, appeared in 2008, just as lots of people suddenly found themselves out of work because of the market collapse.) Language is the key to symbolic systems in human affairs, because being able to communicate meaning reliably to other actors offers a massive upgrade of co-ordination and co-operation potential. But language is also a site of deception, manipulation, psychological pressure and what the philosopher Harry Frankfurt analyzed as ‘bullshit’ — lack of regard for the truth. Our glossaries are whimsical and slight in appearance, but their message is deadly serious. You need to understand the language the gives colour and meaning to your existence; you also need to understand the language of domination and diminution. There’s a reason we look for slogans to help us fight injustice — the truly great ones are like poetry, capturing the truth in a few memorable words. My favourite is from a handmade poster used in Paris during the 1968 demonstrations: La beauté est dans la rue!

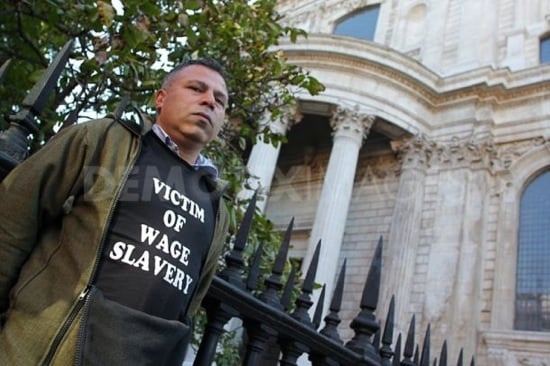

Protester at Occupy Toronto, St. James Park. Photo by Flickr user ryPix.

On Oct. 16, reporting on National Action Day from Los Angeles, the Xinhua News Agency (the official press agency of the government of the People’s Republic of China) related the following anecdote:

Kandist Mallett, a girl at her 20s, told Xinhua she joined the protest because she thought the United States needs a change and she wants to do something to push for the change.

She said she has already graduated from college and has got a job, but she does not want to be a “wage slave.”

“I think young people like me should have better chance to contribute to the society and work more productively instead of being a wage slave,” she said. Her remarks represented some young Americans who have a job but are not satisfied with what they are doing.

On Oct. 15, the University of Toronto’s independent student newspaper TheNewspaper.ca published a review of the WSG. Excerpt: “Faced with unemployment, wage cuts, and the breaking of the social contract, what is your average proletarian to do? He or she ought, of course, to turn to satire. The Wage Slave’s Glossary is a timely work by Glenn and Kingwell.”

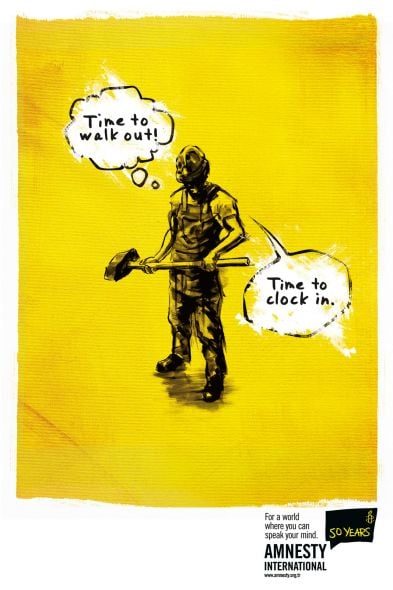

On Oct. 15, the website Ads of the World published the following poster created for Amnesty International by the Istanbul office of the advertising agency Grey Worldwide.

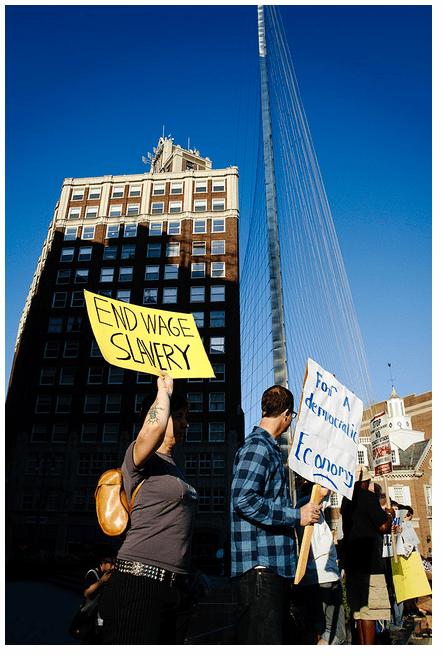

Protesters at Occupy Detroit (Grand Circus Park). Photo taken by Flickr user Stiofan1916.

On Oct. 13, the website of The Atlantic published a slideshow of excerpts from The Wage Slave’s Glossary; the feature was titled “A 21st-Century Guide to the Words We Use at Work.” The introduction read, in part:

Enter The Wage Slave’s Glossary, a fun dictionary of modern office idioms and new economy jargon by Joshua Glenn, Mark Kingwell, and the cartoonist Seth. … First, there are new words coined for our peculiar moment of both hard work and no work (“gigonomics”). Second, some words you know get the historical treatment (“career” initially referred to a circular racetrack, which seems appropriate). Third, words borrowed from our friends overseas help to illuminate office life (“datsu-sara” from Japan: to quit a boring job).

Thanks, Boing Boing, for running a preview of The Wage Slave’s Glossary!

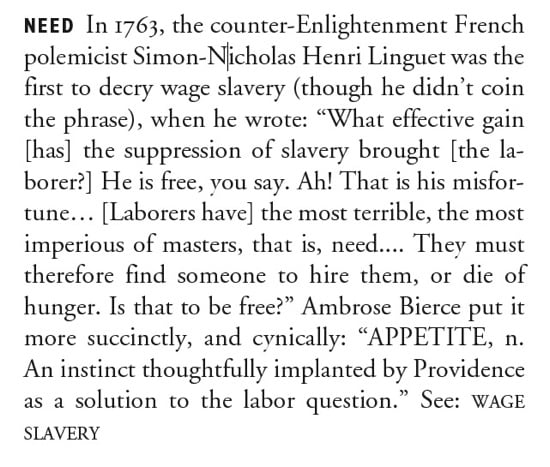

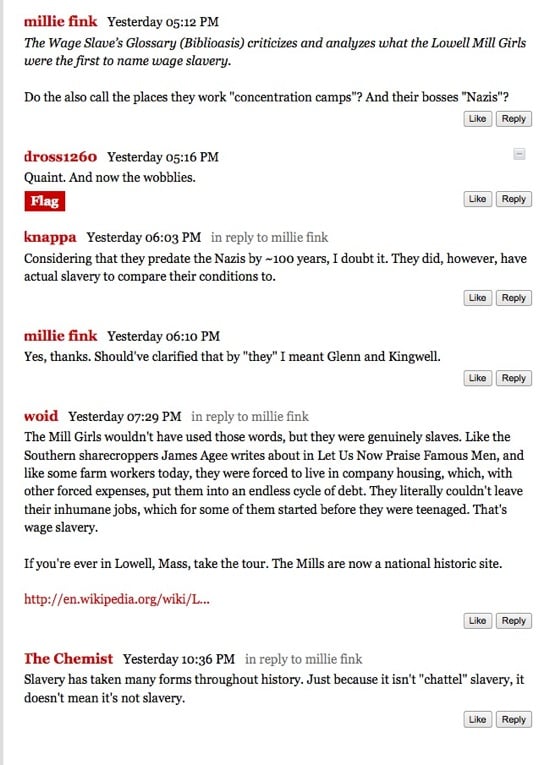

In the comments section, Boing Boing reader “millie fink” takes issue with the phrase wage slave — “Do they also call the places they work ‘concentration camps’? And their bosses ‘Nazis’?.” I might have posted a response, noting that in the WSG we offer historical context for why that term was used by the Lowell Mill Girls, and we note that the term was considered offensive at the time. For example:

Also:

However! Boing Boing users “woid” and “The Chemist” beat me to it, with terrific responses. I love both the question and the answers; Boing Boing readers are the best.

Thanks, Design Observer, for tweeting about the Wage Slave’s Glossary to your 395,000 followers!

Photo of Occupy Rochester protest, spotted in Flickr user Experimental Film’s photostream.

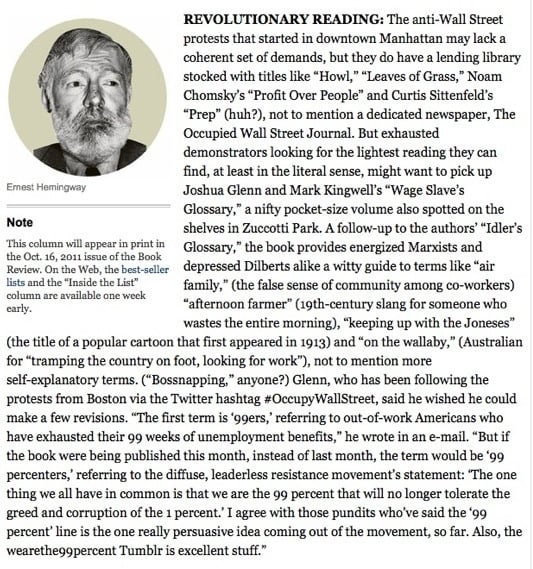

In her October 16 “Inside the [Bestseller] List” column (posted to the NYTBR website on Oct. 7th), the New York Times Book Review’s Jennifer Schuessler suggests that Occupy Wall Street protesters “might want to pick up Joshua Glenn and Mark Kingwell’s Wage Slave’s Glossary, a nifty pocket-size volume … spotted on the [library] shelves in Zuccotti Park.”

Edmonton graffiti posted to the Foundmonton tumblr.

Photo of Occupy Las Vegas protest, spotted in Flickr user Jason A. Karsh’s photostream.

On Oct. 6, in a Slate review, Forrest Wickman notes that a half-baked critique of the alienation of labor is the subtext of the sci-fi movie Real Steel:

The story line of Real Steel begins with one of cinema’s least threatening robot uprisings: Robots have taken over the boxing ring, sending the good-old-fashioned red-blooded boxers out of the arenas and into the unemployment lines. Given this promising setup, the Detroit filming locations, and the populist pride that’s fuel-injected into the film, I’d like to report that Real Steel is a stealth critique of the alienation of labor. The film champions the supreme might of man and machine working in unison, a combination that ultimately wins out over the soulless tech geekery which aims to outmode workers altogether. This conceit is the furious subtext for all the metal-on-metal action. Or maybe it’s just an excuse for fighting robots.

On Oct. 6, a friend of WSG coauthor Josh Glenn’s made this poster, in solidarity and in jest.

On Oct. 3, the establishment-worshipping Washington Post somehow allowed this tidbit to come to light. A sign of the times?

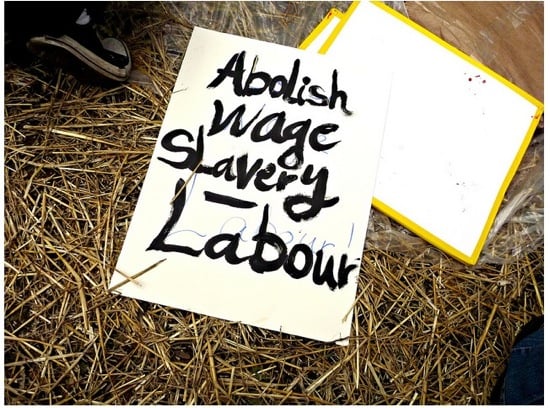

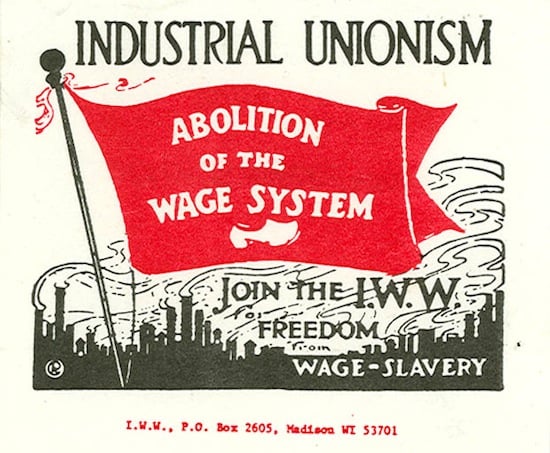

On Sept. 28, the IWW endorsed OWS, which it described as a step in the process of abolishing wage slavery.

On behalf of our union, the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World sends our support and solidarity to the occupation of Wall Street, those determined to hold accountable our oppressors.

This occupation on Wall Street calls into question the very foundation in which the capitalist system is based, and its relentless desire to place profit over and above all else.

When 1% of the ruling class holds the wealth created by the other 99%, it is clear that the watchwords found in our union’s preamble, “the working class and the employing class have nothing in common”, ring true more than ever. The IWW does not follow a business union model. We believe that the working class and the employing class have nothing in common and we don’t foster illusions to the contrary.

Throughout the world, from Egypt to Greece, from China to Madison, Wisconsin, working class people are starting to rise up. The IWW welcomes this. We see the occupation of Wall Street as another step — no matter how large or small — in this process.

According to a September 27 Bloomberg News report, one of the titles in the makeshift library set up in Zuccotti Park is… The Wage Slave’s Glossary.

The book’s publisher, Biblioasis, has shipped a box of WSGs to the Zuccotti Park library. May a thousand flowers bloom.

On September 26, the blog Part-Time Wage Slave posted a jeremiad about wage slavery. Among other points:

You may have the best job in the world, you may be your own boss with the freedom to clock in and out whenever you want. You may get the pick of projects, and work on only those that satisfy and fulfill you. But at some point you’ll still have a tedious meeting to attend, some ridiculous forms to fill in, annoying amounts of paperwork to file and a bunch of other shitty little things that you really wish you could ignore.

Note that TEDIUM is one of the terms glossed in the WSG.

At her Naked Capitalism blog, on Sept. 25 Yves Smith decried wage slavery in a post titled “Welcome to the Police State: NYC Cops Mace Peaceful Protestors Against Wall Street.”

I’m beginning to wonder whether the right to assemble is effectively dead in the US. No one who is a wage slave (which is the overwhelming majority of the population) can afford to have an arrest record, even a misdemeanor, in this age of short job tenures and rising use of background checks.

On Sept. 24, Andrew Sullivan’s Daily Beast blog, The Dish, announced the WSG.

On Sept. 21, Businessweek magazine published the following excerpt of Mary Gabriel’s new book, Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution.

Meanwhile the labor that produced the rich man’s wealth robbed the worker of his lifeblood: “It produces palaces — but for the worker, hovels. It produces beauty — but for the worker, deformity. It replaces labor by machines, but it throws one section of the workers back to a barbarous type of labor, and it turns the other section into a machine. It produces intelligence — but for the worker, stupidity, cretinism.”

Marx sought to explain how this corrosive relationship had developed. He began placing man in a system in which the grand bourgeoisie, which controlled all the money as well as the means of production, dehumanized the worker by reducing him to selling his labor for a wage determined by his employer. The worker in the new industrial relationship became alienated from his work, laboring for a class of men who reaped all the benefits and gave him in return only the means to survive.

On September 20, Kai Ryssdal of the public radio show “Marketplace” interviewed Joshua Glenn about the WSG.

Kai Ryssdal: This next three-and-a-half minutes of the broadcast are for all you “clockless workers,” grinding away in the countless “cube farms” out there. If you need a translation, I direct you to a new book called The Wage Slave’s Glossary. It’s a new collection of terms about work and the workplace. Joshua Glenn’s one of the co-authors. Welcome to the program.

Joshua Glenn: Thank you.

Ryssdal: Why write this book? I mean, we’ve got dictionaries all over the place.

Glenn: Our previous book was The Idler’s Glossary, and that was a collection of terms that were celebrating a certain style of life: the idler’s way of life, where you don’t let work define who you are and what you do. And this one is looking at the other side of that coin, which is the fact that so many of us work at jobs where we don’t have very much control over how we do it, or when we do it — or what we’re doing, even.

Ryssdal: Run me through some of the definitions, some of your favorite key phrases in this dictionary, would you?

Glenn: I’m very interested in all these words that come from the workplace that people use to describe themselves. For example, the word “downtime.” It was a mid-century term that meant time when a machine is out of action or unavailable for use. And today, of course, this means that human beings who aren’t working are compared to machines that are being serviced, or robots that are being recharged. And the worst thing of all, is that many of us now use “downtime” to describe our own weekends and vacations.

We look at a lot of corporate jargon, too, things like the “clockless worker,” “loyalty time,” “flexibilization” — these kind of sinister euphemisms for bad things that corporations like to do. “Clockless worker” being somebody’s who’s willing to ignore what the clock says and just keep working; “loyalty time” being another word for unpaid overtime. Even the word “boss” actually comes from Dutch plantations; a werkbaas was … the overseer of the slaves on the plantation. So the fact that we’ve now come to use “boss” in an almost admiring way — it’s no longer a pejorative — says a lot about how much we’ve forgotten about how work has developed over the years.

Ryssdal: It’s funny that we have so many words relating to and about and of this place where we spend, you know, a third of our lives. It’s kind of interesting that we don’t explore that more.

Glenn: Yeah. There’s a lot of ideas about the nature of work hidden in all of that. For example, there used to be a term in the 18th century called the “after-dinner man,” which was somebody who went back to work after they’d eaten their dinner. At the time, that was considered a very strange thing to do — dinner time’s when you’re supposed to be done with work, why would you go back? Either you’re unhealthily addicted to work or you have too much of it. Of course today, we’re all after-dinner men, and we think nothing of it when people open their laptop after dinner and finish up a PowerPoint or send out some work emails. But once upon a time, only a pathetic individual was an after-dinner man.

Ryssdal: Although it occurs to me that though you and I are having an interesting discussion about all these words that people use for work, there are 14 million people who don’t have jobs who would love to be required to flip on a laptop after dinner or something, you know?

Glenn: Well I don’t know if they would love that, but [it’s true] that they would love to have a job. Once upon a time, there was a quite stark distinction between an artisan and a hireling, or a servant. The artisan was somebody who could direct their own work, who could come and go as they pleased, who wasn’t told how to do what they did. A hireling or a servant was somebody who couldn’t do any of those things. Today, most of us are in the latter category; most of us who have managers or bosses are pretty much told what to do and how to do it.

The book is not against working, per se; it doesn’t say that somehow magically we’d all have to do nothing. But it does suggest that perhaps there’s other ways that things could be organized besides, you know, one guy is the manager and the other person is the worker.

Ryssdal: Yeah. My favorite is “GTFBTW,” which we can’t actually say on the radio, but you can look it up here in our excerpt. Josh Glenn is the co-author of the book called “The Wage Slave’s Glossary.” Josh, thanks a lot.

Glenn: Thanks for having me.

Marketplace excerpts from the book.

On Sept. 20, the independent, unionized Ironsea brand’s website began selling a handmade Wage Slave tote…

Note that their Wage Slave tee is sold out.

On September 17, the Occupy Wall Street protest began.

Photo spotted in Flickr user David Shankbone’s photostream.

In her book review column “The Find,” the Boston Globe’s Jan Gardner says the WSG offers “a wry brand of enlightenment.”

At his blog The Writer’s Muse, Jon Raymond suggests that “wage slaves are not just those working on the low end of the scale. Anyone doing any job or in any career that they are in solely for the purpose of survival, regardless of how lucrative, are a slave to their wages, and live in denial of their own creativity, humanity, and passions…”

In the Sept. 4 issue of The New York Times‘ Sunday Review, Robert B. Reich urges policy makers to boost the purchasing power of the middle class by improving public schools and public transportation, expanding access to early childhood education and higher education, maintaining strong labor unions, enlarging safety nets, requiring big companies to pay severance to American workers they let go and train them for new jobs, pegging the minimum wage at half the median wage, raising taxes on the rich and lowering taxes on the poor, and in general spreading the gains of globalization and technological change more equitably.

Will boosting the purchasing power of the middle class truly make America (as Reich argues, in his essay’s conclusion, via a quote from James Truslow Adams) “a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone?” We beg to differ! A better, richer, fuller life for all has little to do with increased purchasing power.

Elsewhere in the Sept. 4 issue of the Sunday Review, Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer (authors of The Progress Principle) announce that their research, conducted over the past decade, indicates that “workers perform better when they are happily engaged in what they do.” Pressure doesn’t enhance performance; making progress in meaningful work does. Sounds good; so do such sentiments as “Work should ennoble, not kill, the human spirit.” But the authors of The Wage Slave’s Glossary beg to differ with Amabile and Kramer’s solution to the “disengagement crisis.” To wit: “Workers’ well-being depends, in large part, on managers’ ability and willingness to facilitate workers’ accomplishments — by removing obstacles, providing help and acknowledging strong effort.” And “Fostering positive inner lives sometimes requires leaders to better articulate meaning in the work for everyone across the organization.”

No! Workers’ well-being depends, in large part, on managers themselves being removed; and positive inner lives are fostered by work that is actually meaningful, as opposed to meaningless work garnished with a portentous mission statement.

Mark Kingwell’s Introduction to the Wage Slave’s Glossary was published in the July 2011 issue of Harper’s magazine.

DISGRUNTLED: Charlie M. writes: “The Wage Slave’s Glossary is missing one very important entry, ‘Disgruntled Employee.’ ‘Disgruntled Employee’ is is one of the most popular terms used to blacklist/blackball/stark-mark, etc., someone from employment or opportunity. I and others have been labeled with this term by people who have treated us unfairly while depriving us of the civil and human rights required to achieve justice. The term effectively transfers guilt to the employee.”

STARK-MARK: Charlie M. writes: “Stark-mark” is a deliberate blemish put on the paper of a job reference. The job reference says good things but the stark mark is code for “Do not hire.” The practice was especially popular in the USA with railroads and mining companies when phones were less common.

THE ITIS: The general feeling of lethargy and well-being experienced after eating a satisfying meal.

DRAPETOMANIA: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drapetomania

Bukowski on wage slavery and his escape from it:

http://www.lettersofnote.com/2012/10/people-simply-empty-out.html

From Rob Wringham: It’s not as great a find as “drapetomania”, but in reading a history of the English language I came across “slubberdegullion”, a seventeenth-century term “signifying a worthless or slovenly fellow.” Also, “velleity”, “a mild desire, a wish or urge to slight to lead to action”. How familiar a notion that is to idlers! Taken from Bill Bryson’s “The Mother Tongue: English and how it got that way”.

[Occupy Wall Street protesters] might want to pick up Joshua Glenn and Mark Kingwell’s Wage Slave’s Glossary, a nifty pocket-size volume … spotted on the [library] shelves in Zuccotti Park…. A follow-up to the authors’ Idler’s Glossary, the book provides energized Marxists and depressed Dilberts alike a witty guide to terms like “air family,” (the false sense of community among co-workers), “afternoon farmer” (19th-century slang for someone who wastes the entire morning), “keeping up with the Joneses” (the title of a popular cartoon that first appeared in 1913), and “on the wallaby” (Australian for “tramping the country on foot, looking for work”), not to mention more self-explanatory terms. (“Bossnapping,” anyone?) — New York Times Book Review column “Inside the List” by Jennifer Schuessler

A 21st-Century Guide to the Words We Use at Work. Alaskans have more than 100 words for snow, as legend has it. So it’s only appropriate that Americans, who work longer hours with fewer paid breaks than almost any other developed country, would have hundreds of words for working. Or, not working. In our current crisis, consider the panoply of terms for being let go from work: there are layoffs, furloughs, firings, redundancies, non-renewals, partings, breaks, and, finally, funemployment. It’s exhausting just to count the synonyms. Enter The Wage Slave’s Glossary, a fun dictionary of modern office idioms and new economy jargon by Joshua Glenn, Mark Kingwell, and the cartoonist Seth. … First, there are new words coined for our peculiar moment of both hard work and no work (“gigonomics”). Second, some words you know get the historical treatment (“career” initially referred to a circular racetrack, which seems appropriate). Third, words borrowed from our friends overseas help to illuminate office life (“datsu-sara” from Japan: to quit a boring job). — feature from The Atlantic.com

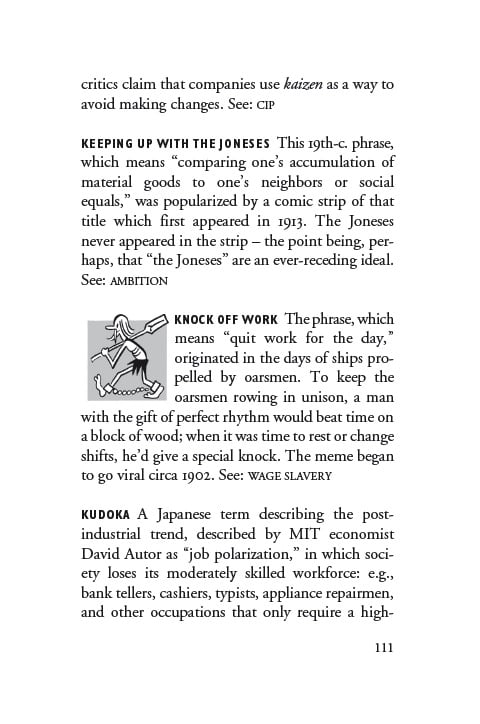

Joshua Glenn and Mark Kingwell, creators of The Idler’s Glossary, offer a wry brand of enlightenment in their pocket-sized guide to the terms of paid labor. The phrase “Keeping up with the Joneses’’ sprang from a 1913 comic strip in which the Joneses never appeared. And they trace the origin of “knock off work’’ to the days when oarsmen rowed in unison and a special knock would signify a time to rest. — Boston Globe column “The Find” by Jan Gardner

It’s funny that we have so many words relating to and about and of this place where we spend, you know, a third of our lives. It’s kind of interesting that we don’t explore that more. — Kai Ryssdal, host of public radio’s “Marketplace.” Click here for transcript of show.

Think of this tiny volume — ably buttressed by a nimbly delightful introduction from Mark Kingwell and the art of Seth — as an obverse companion [to The Idler’s Glossary], a book dedicated to resistance to work and the corporate language that supports it. Example: A clockless worker is “an employee who doesn’t leave her job behind at 5 p.m. because she has internalized management’s ‘clockless’ definition of the workday.” Topics such as Break and Retirement get similar deconstructions. Subversive stuff. — Toronto Globe & Mail

Faced with unemployment, wage cuts, and the breaking of the social contract, what is your average proletarian to do? He or she ought, of course, to turn to satire. The Wage Slave’s Glossary is a timely work by Glenn and Kingwell. — review in The U. of Toronto’s independent student newspaper, TheNewspaper.ca

My friends Joshua Glenn and Mark Kingwell wrote a gem of a book called The Wage Slave’s Glossary, which was designed and edited by the great cartoonist Seth… [A] very entertaining little book. — Boing Boing post by Mark Frauenfelder

Alongside other witty and rousing definitions, The Wage Slave’s Glossary gets to the nub of the wage slave matter. … There are obvious parallels between white-collar mediocrity and actual enforced labour. As long as we have to work for someone else in order to pay for the modest spaces we occupy (on once-common land, forcefully confiscated by people who aren’t even alive any more), we are not free. — review from the blog New Escapologist

A small but attractive and useful gift. — tweet from Design Observer

WE WANT: Mark Kingwell and Joshua Glenn’s latest point of purchase impulse-buy compendium, The Wage Slave’s Glossary. Don’t know what to “fossick” means, and why no journalist should do it? See, now you want it, too. — The National Post, “Snap Judgments” column

I strongly recommend this book, which is wise, witty, and — too often — sad. — Career Calling blog

Joshua Glenn is an independent scholar and freelance cultural semiotics analyst. He’s cofounder of HiLobrow. He has labored as a bicycle shop manager and skateboard courier, a handyman and house painter, and also as a magazine (Utne Reader) and newspaper (Boston Globe) editor.

Mark Kingwell is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto, a contributing editor of Harper’s magazine, and the author of fifteen books.

Seth is the cartoonist behind the comic book series Palookaville. His books include It’s a Good Life if You Don’t Weaken, Wimbledon Green, Bannock, Beans and Black Tea, and Clyde Fans Book One.