OFF-TOPIC (60)

By:

April 23, 2024

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This time, conversation with a premier creative appropriator on where to look for realness…

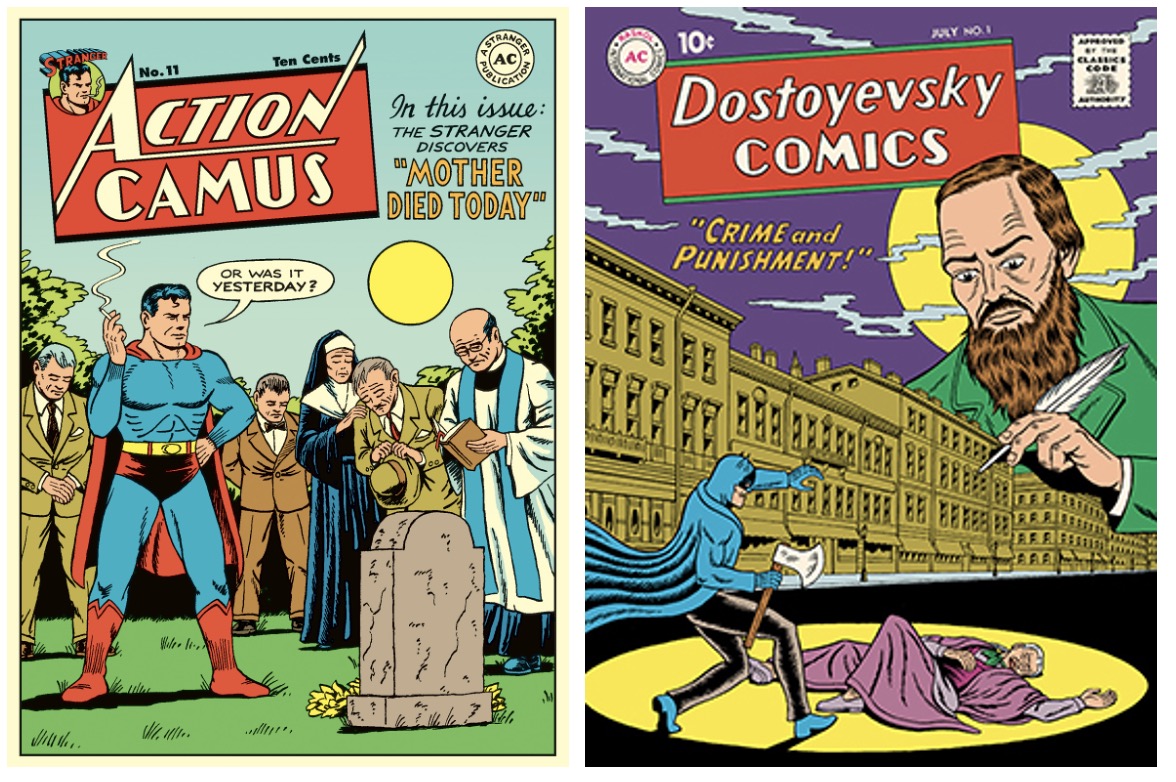

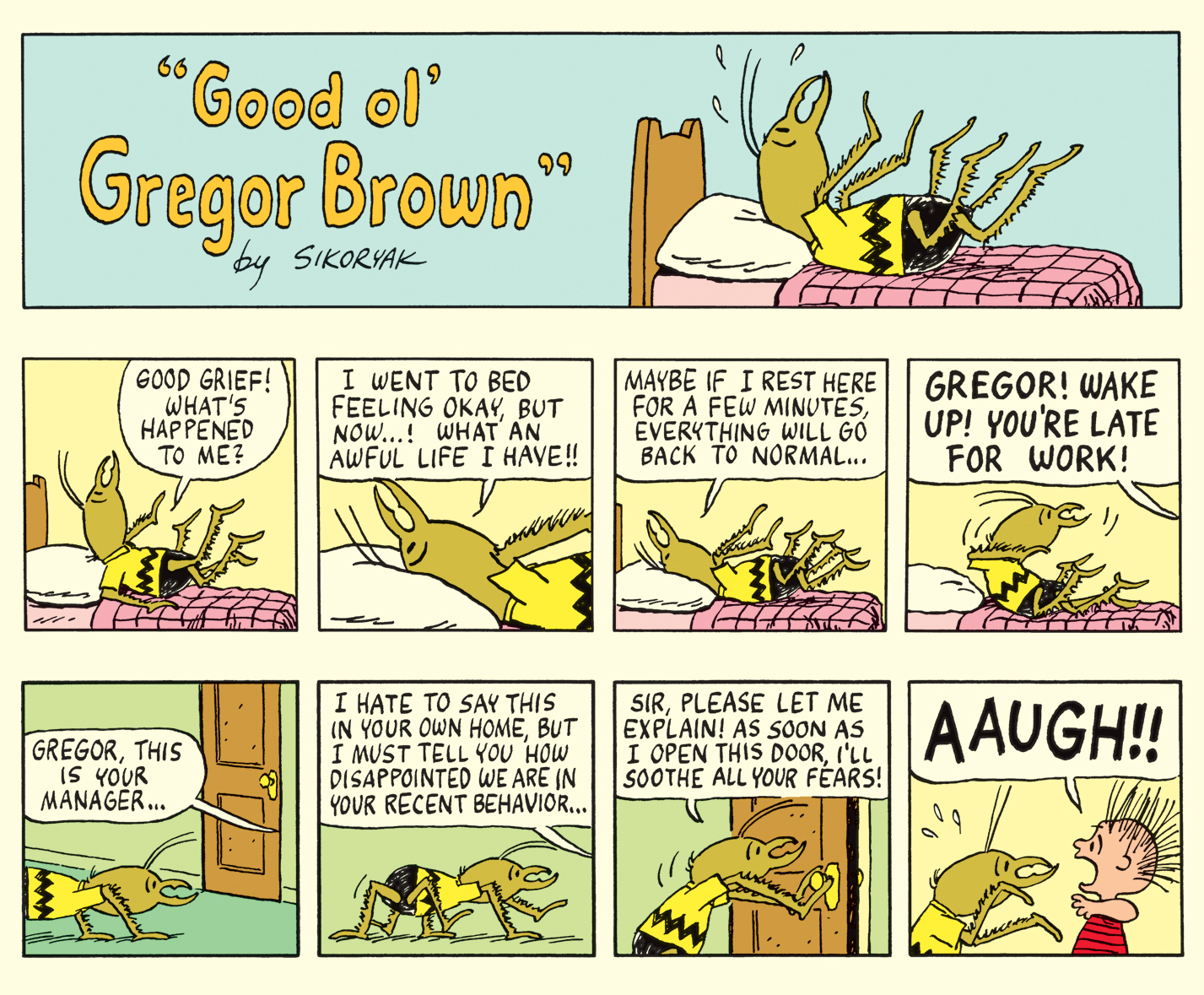

It used to be said of good actors that they could entertain an audience even by reading the phonebook; R. Sikoryak is the guy who could probably draw it. He’s come close with Constitution Illustrated, which brings our founding document to life in articles enacted by classic and current cartoon characters, and Terms and Conditions, which converted Steve Jobs to a different comic avatar on every page of a verbatim adaptation of the infamous iTunes “contract” with users. He built up to these longform attention spans with Masterpiece Comics, his collection (and ongoing series) of literary classics condensed to a few pages of graphic narrative in an aptly matched style from some almost-as-vintage superhero or Sunday-funnies scamp.

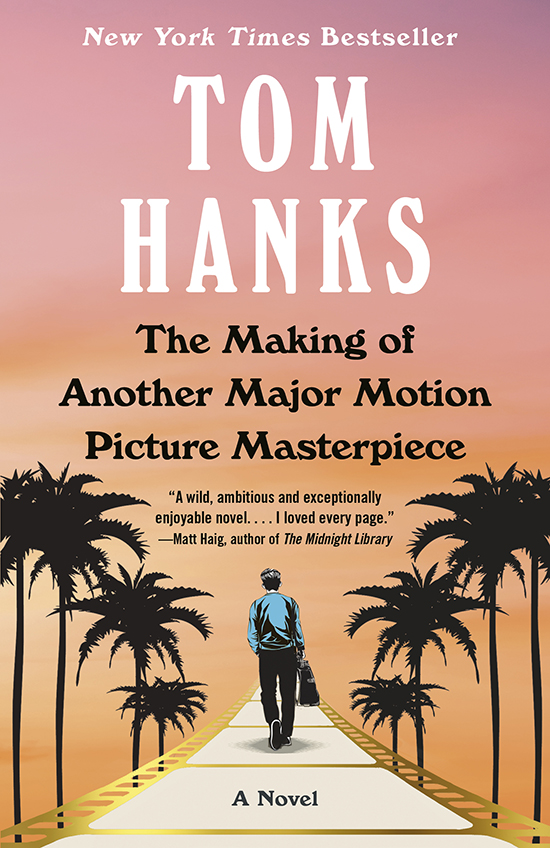

But I started off with an actor comparison, and that’s what brought us in contact this time. Tom Hanks published a novel last year, The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece, which incorporates three comicbook interludes in different period styles by R. A book which sounds wryly titled after one of its author’s own review-blurbs while nodding to Dave Eggers’ A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius seems the right match for Sikoryak’s astute and pastiche-based style to begin with, and the compatibilities don’t end there.

As Sikoryak put it to me in a convo during a small-press comics con this spring, “It’s about how pop culture reinvents itself,” and the fit was fated because “that’s all I do!” In his prose, Hanks catches the cadence of our times and several others like Sikoryak can pick up the style of any visual genre and fan culture. The book spans the life of a cartoonist born in post-WWII picket-fence America, his young adulthood in the stoner golden-age of late-1960s/early-’70s psychedelia and dissent, and, for the bulk of the book, the equally epic and unreal-seeming wonderland of 2020s blockbuster Hollywood.

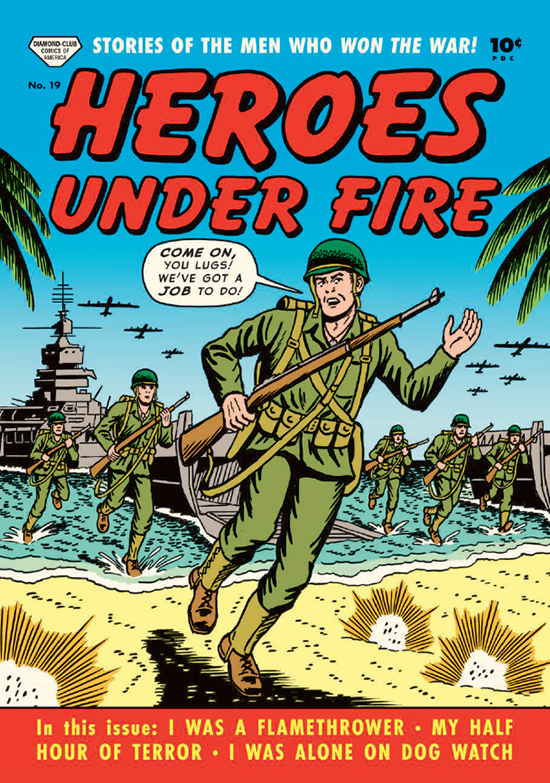

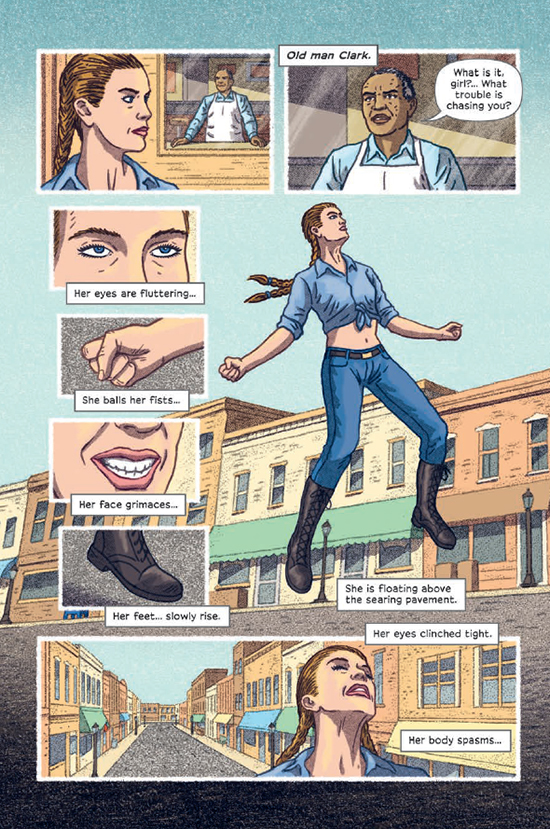

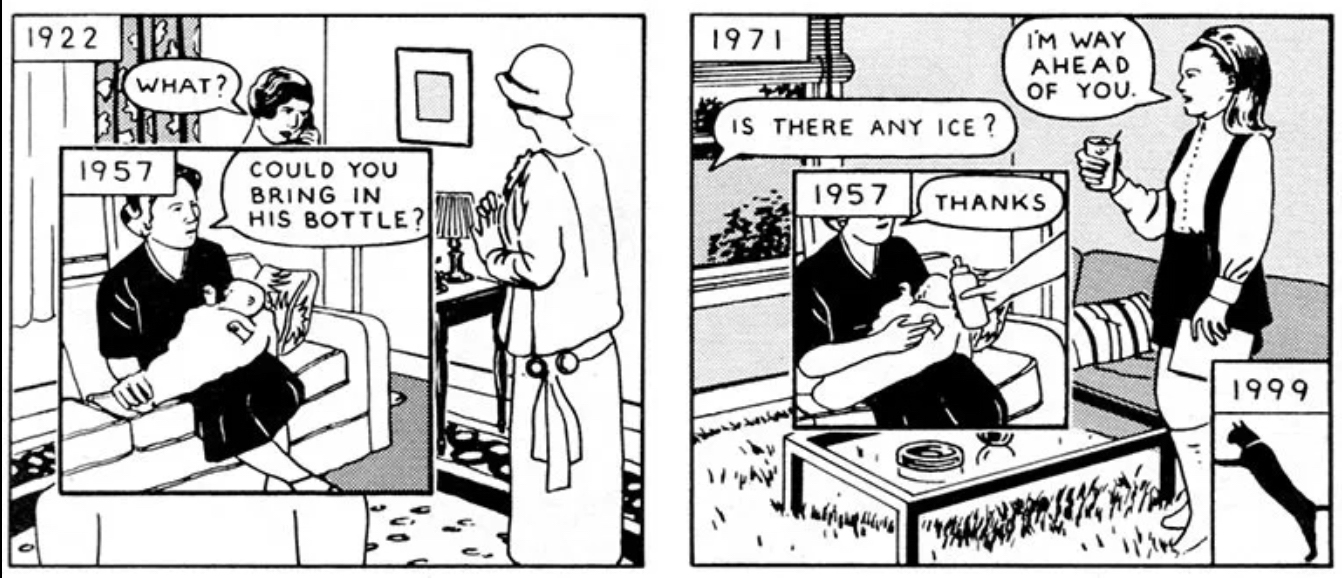

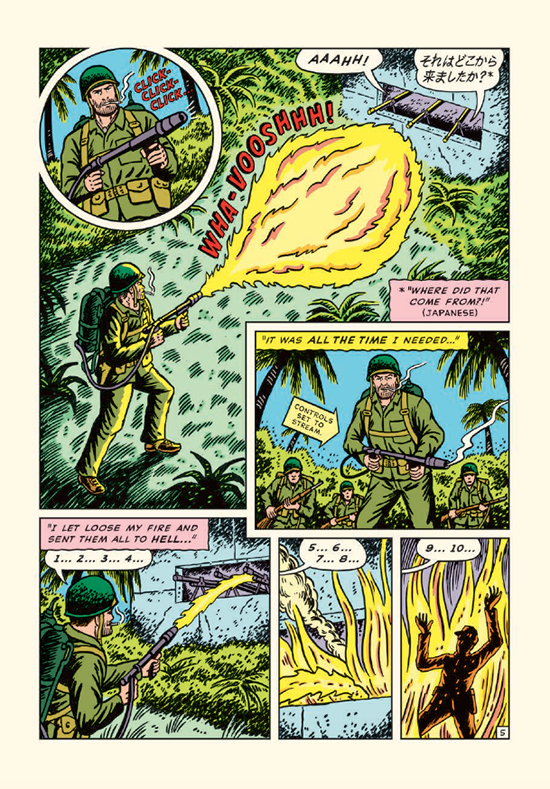

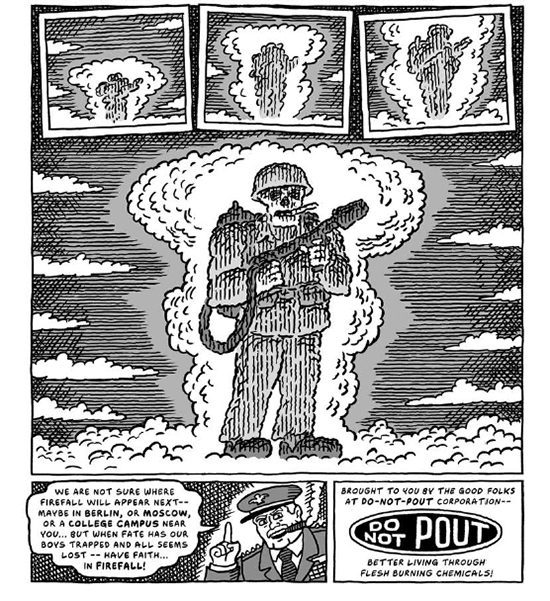

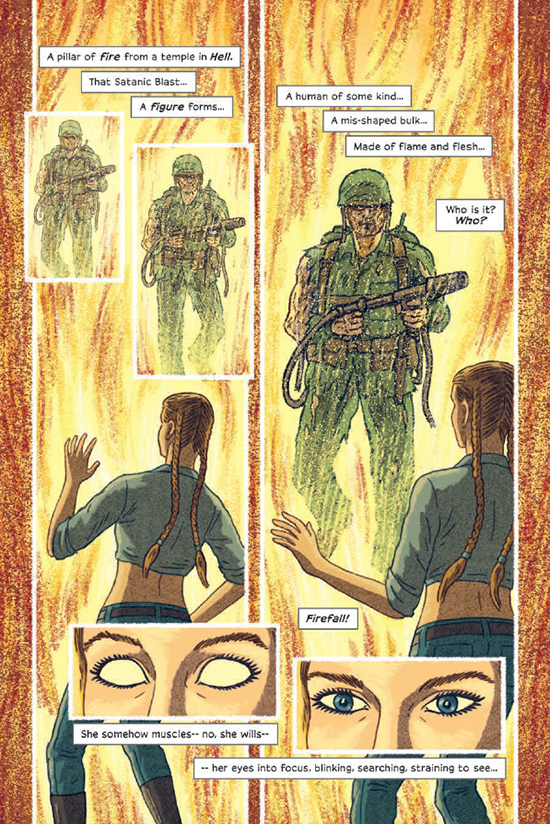

A Nolanesque filmmaker is convinced to do a superhero franchise film but insists on doing it his way, composing a conflicted romance and tale of weary warriors based on a troubled modern superheroine property (Eve Knightshade) and an obscure “underground” comic from 50 years ago about a haunted, macabrely humorous flamethrower-wielding WWII soldier (Firefall). We meet the young artist in ’40s and ’70s flashbacks, as well as his battle-scarred, biker-gang uncle (the real-life model for Firefall), and a cast of vivid yentas making a new movie out of this fact and fiction. The brisk and perceptive prose zooms out for three short comics drawn by Sikoryak: “Heroes Under Fire” from 1947, which burns its way into the child artist’s mind and triggers darker memories in his uncle; “The Legend of Firefall” from 1971, which burlesques the older comic and the then-current Vietnam War with mock patriotic fervor yet an undercurrent of sad sympathy; and “Knightshade: The Lathe of Firefall,” a 2020s movie tie-in that takes contemporary comics’ more internal and reflective point-of-view on traumatized, reluctant heroes. (To complete the collection of meta souvenirs, you can QR-code your way to the faux movie’s full screenplay too.)

It’s a milestone in comics’ cultural acceptance to be incorporated into a literary novel in this way, and Hanks’ narrative extends the magnanimity to his portrayal of the now-embattled superhero movie genre itself, finding the human fiber to be cultivated there. Though that’s really incidental to his primary aim to train a camera on what people are talking about today and the way they talk; the novel snaps a detailed and forgiving portrait of the American character circa 2024, in all its cacophony of multiple cultures and identities striving and competing for a shared, shaky future. It’s a post-it board of past and present, dignified people in crap jobs and flawed human beings in exalted ones, with a panoramic eye for varied walks of life and pinpoint reflexes for telling details (in a cast of everyone from factory laborers to rideshare drivers, caterers and petulant megastars, what Moby-Dick did for rope and ambergris this book does for short-order cooking, hospitality franchises, gig economics, childcare, and cosmically mysterious artistic inspirations). Not just “how a movie is made” (which we learn), but the essence of creativity itself (a process notoriously hard and rare to capture), how a lot of everything else is done, and above all how myriad individual lives make up a crew, a community, a country.

Sikoryak and I rolled zoom cameras on a Q&A about his work’s own wide view and the part that everything plays…

HILOBROW: Thanks for doing this! Questions will run from the vapidly Who-What-When-Where-Why to the more probingly philosophical [laughter]. Could you state for the record how this came about, and how the writer and publisher found their way to you?

SIKORYAK: I never quite found out what the specific way they found me was [smiles]. Interestingly — I’m already gonna have a tangent here — I illustrated a book about Tom Hanks written by my friend Gavin Edwards, who I worked with on occasion; I illustrated a number of books by Gavin Edwards on different celebrities, I did one on Bill Murray, I did one on Mr. Rogers and I did one on Tom Hanks. It came out… 5 years ago? I didn’t expect anything to come of that, specifically. But then, out of the blue, I got an email from Tom’s editor at Knopf, and he said “Tom is writing this novel that’s got comics in it, and we think you’d be good for it; you’d have to audition for the job.” I had a zoom meeting with Tom and the editor, and I was very nervous [laughter], although the first thing the editor told me was, “Tom is as nice as you’ve heard,” and he was super-nice through the whole process. He told me the basic notion of the book being that there would be three different comics in styles that spanned about 70 years, and that was so up my alley I was really excited about this. I got some pages of the book, and started working on the comic from there. I didn’t actually read the whole novel before I drew the comics, because I believe he was still writing it as I was drawing it… but, how they found me? I’m not exactly sure. They may have seen the book I illustrated — it was done in 25 different styles as is my way — they may have also seen my website; The New Yorker is pretty high-profile, maybe they found me through there, I’m not exactly sure. I always wanted to ask, and then it never was convenient [smiles]. They did tell me they were looking around, and thought maybe I would be the best, since it’s kinda my specialty; when I heard the conceit of the book, which is basically one character taken through iterations of time in comics history, I was like, I’ve already kind of played with those ideas for my whole career, so it… felt like it was written for me.

HILOBROW: It is fateful — aesthetically for sure, since the prose part so adopts the vernacular of different times, it really struck me as an analog to your command of period styles. The way he has an almost flawless grasp of 1940s, 1970s speech patterns — and then, no small feat, how he has a great ear for the “period” of the present, which is not as easy as it seems. It feels like a time-capsule of Twenty-Twentysomething; it won’t get dated, but it seems like somebody who really has their ears open.

SIKORYAK: Well, it’s his world, and he’s said in interviews that the things that happen in the book, on the set, are things within his experience, but it does feel very much of-the-moment, as opposed to his career which has spanned, what, 45 years now.

HILOBROW: It’s fascinating you said you did some, or maybe all of the comics before you had the full prose novel to read; that kind of replicates the whole shooting-out-of-sequence nature of a movie.

SIKORYAK: I [did] draw the comics sequentially. I thought about them all at once, [the team] wanted me to lock in styles and approaches for each one, but when I went back to finish the drawings, I did it sequentially, so I drew the 1940s piece first, and the 1970s piece next, and the contemporary piece at the end. Which for me just made sense… the ’70s comic was drawn by someone who had read the ’40s comic, so I felt like I needed to resolve the ’40s one before I could go to the ’70s, and of course the one that’s contemporary is based on the other two. So I did draw in order, but I guess I was doing “method” because I wasn’t reading the other stories that I didn’t know about? [smiles]

HILOBROW: Speaking of “the period of the present,” I was curious how you came up with the modern-day one, because… the present isn’t “locked” as they say about a finished movie; we don’t know how to define the current era while we’re in it like we do with past ones. And since you are contemporary, doing the current one would answer, “What is Bob’s ‘own’ style?”

SIKORYAK: That was the one that really stumped me. It’s impossible to capture the moment — for me; I could not figure out how to do it, I need something to bounce off of. And I was certainly looking at a lot of artists, and Tom had some suggestions… in terms of finding the style it was really tricky. I was thinking, well, the conceit of the [modern] comic is that it’s the adaptation of the movie being made in the book, so I thought, let’s look at contemporary movie adaptations. I was trying to think of a way to look at it through that lens; like, if I’d seen the movie or production stills, how would I draw the comic.

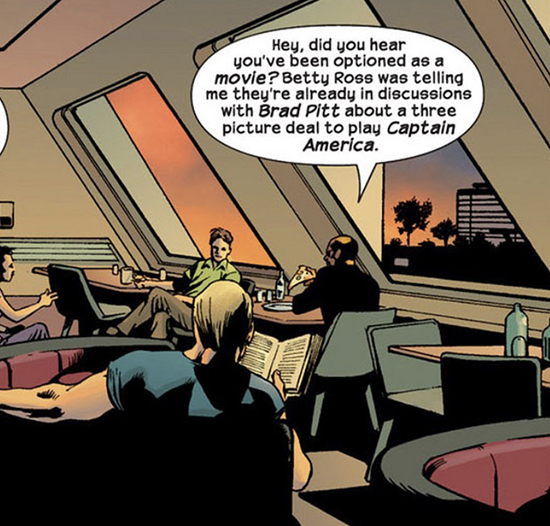

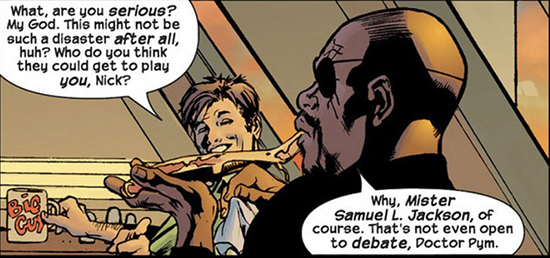

Tom was really adamant that he didn’t want the last one to look like the other comics. Originally I was doing something that looked a bit like Bryan Hitch, because his comics sort of scream storyboard, and have cinematic qualities. But I was like, I can’t draw like him, I don’t know how he does this! And of course none of the actors exist that I’m putting in this movie adaptation, they’re all fictional characters. So I talked to Tom about what actors should I reference, and he gave me some suggestions on that front; obviously I didn’t want to make it any one particular person… but anyway I was looking at Bryan Hitch and going wow, this is gonna be really hard [laughs], but Tom was like, “Don’t make it look like the other two comics,” and I was doing contemporary superhero drawings that looked like inked, Bristol board drawings, and that looked a little bit like the ’40s one and he really wanted me to steer away from that. So he said “Have you ever seen this graphic novel Here by Richard McGuire,” and it was wild that he thought of that one (and there was a story about him having optioned that [Ed. note: It’s out this November!]). I love Here and I’ve known Richard forever; I was working at Raw when Art and Françoise published the first version of Here in 1989. But… Richard doesn’t do superhero comics, how do I make it feel like a superhero comic but still use what he does? I think Tom was really inspired by the broken page layouts, the inset panels, panels within panels… but I didn’t want to do a one-to-one pastiche of Richard. So then I was looking at people like Alex Maleev, even at Bill Sienkiewicz, people who worked with photos but treat them and make them a bit more graphic…

HILOBROW: There was definitely — whatever this means these days — an “indie comic” feel to the final comic in the book, and to me it almost was an illustration of the… spirit that was described for the movie, that it was supposed to be an art film about superheroes, and thus you were doing a kitchen-sink, quiet superhero comic. An illustration of a period’s aesthetic without being a particular style… quite an elusive thing to pull off.

SIKORYAK: For all three stories I was trying to synthesize different influences into one style that could represent the era. But as you say, it’s really hard to do that in the present. That you picked up on the indie vibe makes total sense to me because that’s my roots and I can’t really escape that [laughs]. It’s still a little hard for me to talk about that one, because it was the most elusive.

HILOBROW: I would imagine there was also a real challenge depicting an era of style as opposed to a particular artist’s for the ’40s and the ’70s one because, yet again, it wasn’t your usual remit, where it’s like, “Let’s take a Dostoyevsky story and give it a Dick Sprang visual style,” this had to be, instead, one of many war comics that a kid would’ve picked up in 1947 or whatever, and it had to be a representative but not specific underground that might have been made in the ’70s.

SIKORYAK: Yeah, the thing that made it easier going back in those eras was I could recognize the biggest influences — and maybe that’s the difference of today, we don’t have one influence that seeps everywhere. But in terms of the ’40s comics, I was looking at Simon & Kirby a little bit, and you might see some of that in the panel arrangements, not so much in the drawing; in the drawing I was really looking at Caniff because I thought, everybody loves Caniff, everyone talks about Milton Caniff as being the biggest influence on American comic books of that era. Then I was like, okay, I’ll just do a bad imitation of Milton Caniff because that’s what everyone was doing [smiles] — I mean, “bad,” I worked really hard on it, but it’s not slavish… if I was doing a full-on Milton Caniff pastiche I would be very careful about the panel compositions and the page breakdowns, and even the poses; I’m usually very specific about trying to find reference poses for actions, but here I didn’t worry about that so much. I actually bought model soldiers with flamethrowers that I could pose and photograph, and then I sort of did drawings off of those but I would go back to my Terry and the Pirates books to see how Milton Caniff would ink the soldiers’ uniforms or shrubbery or other aspects of the background. So it was still a composite but I knew I had to anchor it, with Caniff in there someplace.

And then for the ’70s comic, I was really leaning toward Crumb because everybody was riffing on Crumb, and Tom again said, “Don’t make it look too much like Crumb”…I was trying to find that balance; I was looking at Kim Deitch, his storytelling, even the kinds of narratives he writes seemed appropriate for the story; then I found this great S. Clay Wilson page, with this completely obscene character in front of these panels, the character in front is doing something unmentionable and the panels behind him are kind of scattered, so I sort of replicated that [arrangement] of panels… overall, I was trying to find page layouts and storytelling devices that were used in 1971, I was really trying to be specific to that. Instead of finding one artist, it was finding as much reference from as many different people and then mashing it together. Oh, of course I also made fonts for the historical stories too, I wasn’t gonna just find a font that someone else used, so — I mean, they would’ve been hand-lettered [laughs] — but I did make fonts for each of the stories, so the ’40s font is in a Simon & Kirby lettering style…I was very specific about that as well. Only the contemporary story uses existing fonts, from Comicraft, as many contemporary comics do.

HILOBROW: You said “method drawing” before, and it is that kind of thing, you’re placing yourself into, what would have been seen at this time in history, what would people have been reading and thus what would have come out. I also found it interesting that… in a way, you’re always creating behind a persona, because you adopt styles, and even Hanks’ prose is framed by an alter-ego, it’s supposed to be this film teacher from Montana who wrote this book. I can’t ask you why he did it [laughs], but do you have a particular feeling about… is there a certain liberation, or relief, or, what are the advantages of… authoring the author of your work?

SIKORYAK: Oh, they’re endless! I’m a very private person, and… I’m comfortable onstage [laughs], in public places, but I also don’t, I’m not interested in doing autobiographical work; there’s a quote from Oscar Wilde that if you want someone to tell the truth, give them a mask. And I always feel that perfectly sums up why I work this way. Because I think I can say whatever I want in these different guises, and it gives me a lot of latitude. It’s also fun to dress up! [laughs] But I think there’s something about having that distance that lets you comment on things and maybe look at things more objectively. It’s funny, I forgot about the narrator at the beginning of the Hanks book because I don’t feel like… that character becomes invisible by the end of the book, we don’t really go back to him.

HILOBROW: He falls away pretty quickly, yeah.

SIKORYAK: Very quickly! But yeah, I guess, I suppose as an actor he needed someone to play the part!

HILOBROW: A good way of putting it. And… in the same way that different wheels start turning in the prose narrative and they mesh in unpredictable ways years or decades down the line, y’know, from this cartoonist kid in smalltown California in the 1940s to the glitz of contemporary Hollywood, I do think — like when you said before it felt like it was written for you — it seems fated that your two personalities came together on this, because there’s… a generosity to his writing, and to your process, that I think is rare, and matches. I know they say there’s no parody that doesn’t have some affection, but at the same time I think no pastiche doesn’t have some derision…

SIKORYAK: [Laughs]

HILOBROW: …and yet, if there’s an example that doesn’t, it’s yours. And I thought that meshed well with the way that Hanks gets into so many different characters’ heads and seems to have a real conversance with how people who have to work for a living, live, and how they think. So I wondered if there’s a fundamental “agenda of understanding,” so to speak, even if it’s unconscious, in the way that you do your work — because you are getting yourself into so many other creators’ heads, just like he was getting himself into so many characters’ heads.

SIKORYAK: I do try to walk a line, I do try to respect the source material, always. When I started doing this it was much easier to sort of look to the pantheon of cartoon gods and parody them and pull them down to my level or what have you. It’s interesting doing that with contemporary artists, and artists who are younger than me; I’m hoping they recognize that I’m doing it with affection and compassion; I want these things to be seen by the creators as an homage. It maybe goes back to acting again, taking on that persona, and trying to understand how other people think, and trying to get an appreciation for what they’re doing by really studying their work intently.

HILOBROW: If I were a younger cartoonist I’d think, Oh my god I’ve been pastiched by the best, I’ve arrived if Sikoryak has adopted my style.

SIKORYAK: That’s what I hope to hear. The people I’ve showed it to have always seemed very pleased about it, but I don’t talk to everybody.

HILOBROW: As a reader, it gives me a warmth of recognition, when newer styles show up in your work, like a Lee or Liefeld. It’s so far afield from a style that would be expected of you, or I daresay might even be “approved” by some of your peers, that it gives me a sense of community when I see you pastiche styles like those as well, because it does feel like a certain acceptance; there’s no part of the contemporary conversation that you’re dismissing. I do like Jim Lee, I don’t happen to like Liefeld, but no one could possibly like every artist that you have at this point pastiched, and yet they’re all let in.

SIKORYAK: Right! Yeah, that’s my utopian hope [smiles]. There’s a big change that’s happened since I was working at Raw in the late ’80s and early ’90s to today. I remember noticing this years ago, I did a panel with Michael DeForge, must have been 10 years ago now, and it was so great. When he was starting out he was doing a lot of pastiche, a lot of weird, funny Spider-Man comics and things like that. I loved seeing younger generations — not just Michael but other people of that era — who basically said, “Yeah, it’s all comics”; there wasn’t that boundary [between mainstream and indie] anymore, by the 2000s, or 2010s, certainly. People grew up reading Love and Rockets and Frank Miller, or Calvin and Hobbes and Julie Doucet, and the whole spectrum, and then manga [became] so huge in America, and it was just great to see it all mix and match; and at this point sometimes it’s hard to know where people get things from, so just sort of acknowledging all of it seemed right.

And with my work, I’m always trying to let in the reader, and one way to do that is put in something they recognize. And it’s been really gratifying, I actually did a talk at Montclair Library in New Jersey last month, and showing the Constitution pages to young kids and them screaming out, “Oh it’s Adventure Time,” “it’s Dog Man,” they’re yelling and pointing out the characters they recognize. But there’s no way — let alone liking, there’s no way everyone would know all the comics I’ve parodied, because I wouldn’t have known all the comics I’ve parodied, if I didn’t make the book; if I didn’t spend the time seeking out stuff for my work.

HILOBROW: That’s a good look into your process; I have in the back of my mind wondered, “Did Bob naturally encounter all of this stuff or does he go looking for some of it.”

SIKORYAK: Oh no, when I’m working on a book, especially like the Constitution, I was looking at the comics bestseller lists; when I was doing the iTunes Agreement, which has like 100 different styles, I went to the iTunes store and saw what comics were popular, and was like, well, if it’s popular on iTunes it should be in my book.

HILOBROW: I love that — more method-drawing!

SIKORYAK: It’s a constant struggle to keep up. [laughter] The thing that gets me about the [Hanks] book in general is, you said “generosity” before, and I feel like there’s a lot of that. The book could exist without the comics, it could function without them. But he wanted to put everything in, and I just love that he poured so many different elements into it. It was really gratifying to see it, and when I read the whole book I was like, oh it makes total sense that he included the comics because he takes care to introduce all the people who work on the movie. It’s like, let’s make sure everything is accounted for and addressed, given a moment. So it felt of-a-piece with that.

[Images (top to bottom): Portrait of the artist as a founding father, courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly; a masterpiece comic, ©2023 R. Sikoryak; cover to the paperback edition (self-explanatory); from The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece by Tom Hanks, vintage comic book cover illustration by R. Sikoryak (Copyright © 2023 by Clavius Base, Inc.); two more masterpiece comics, © 2023 R. Sikoryak; a “modern” page from the Major Motion Picture Masterpiece illos, same Clavius Base copyright; two panels from The Ultimates #4, © Marvel Comics, art: Bryan Hitch, text: Mark Millar; two panels from the orginal Here (1989) by and © Richard McGuire; a vintage comic book page for the Hanks book by Sikoryak (copyright, ditto); details from two “1970s” pages for the Hanks book by Sikoryak (no way am I typing out all that copyright info again); one more modern page by Sikoryak (you get the idea, and it’s copyrighted and it’s spectacular)]

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE